Is there anything that can lower DHEA? Also, is there any information about the cause of PCOS? I keep hearing it is Insulin Resistance, but my Insulin/Glucose were only midly resistant, but my DHEA is three times too high. I don’t see Insulin as preceeding the high DHEA due to DHEA being so high and Insulin/Glucose not as bad. I have read about Spearmint Tea being able to lessen hirsutism in PCOS women, but by what mechanism? Does it lower a particular androgen or all of them? I also read both Spearmint and Peppermint tea are unsafe, is this true and what is the safe amount?

Also, what about Saw Palmetto? I read it can cause sterility/impotence/permanent loss of libido. Is this true and were any of these effects reported by women? Does it lower all or a particular androgen?

Can you please give me information about Maca Root and how it effects the body? Is it healthy? Is it safe? Is it actually good for hormones/fertility? What about PCOS, would it have a positive effect? I have PCOS, Insulin Resistance & High DHEA are my only known imbalances. I have read Maca will make me more masculine & I have also read it can cause heart palpitations & is a stimulant. I also read gelatinized is best, but concentrated. Please help.

Ava/ Originally posted in Enhancing Athletic Performance With Peppermint

Answer:

These are certainly good questions! First, it’s important to know exactly what polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is and how diet may have an impact.

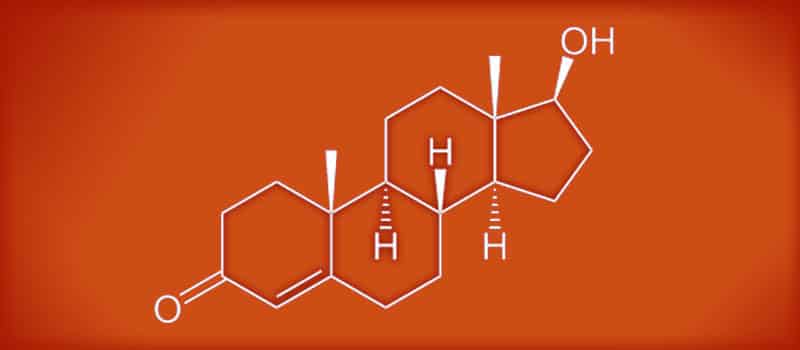

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common ovarian disease, associated with excess androgen in women. The cause is unknown affecting roughly 6-20% women (depending on diagnostic criteria). Common signs are hirsutism (excess hair growth), anovulation, and obesity, with signs of the disease likely generating in adolescence. Some women may not be obese and present only with anovulation and high levels of angrogens. Affected women generally have multiple ovarian cysts and may be infertile. PCOS is tightly related to metabolic issues like insulin resistance/glucose intolerance, and obesity. Women are more likely to develop earlier than expected glucose intolerance states boosting the risk type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. It is hypothesized that excess levels of circulating insulin may decrease the concentration of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG – a beneficial hormone that helps removes excess dangerous hormones from the body), thereby increasing the amount of unbound free testosterone. Modifying sex hormones may be a useful to improve symptoms and risk factors associated with PCOS. Inflammation also seems to play a role, as C-reactive protein (CRP) levels appear to be elevated in young women with PCOS. Adopting a healthful diet in adolescence may lower risk of developing metabolic complications associated with PCOS. One study found young women with PCOS tended to have lower fiber intake, poorer eating pattens (eating late at night) and over-consumed calories. This type of eating pattern can lead to weight gain, which unfortunately is one of the largest problems surrounding PCOS. The good news is if we know some of the factors helpful for weight loss PCOS can be better managed.

Obesity tends to exacerbate almost all diseases and PCOS is no exception. Obese women with PCOS tend to have increased free testosterone (a common type of androgen hormone) and more insulin resistance. The obesity and PCOS connection is so strong research suggests prevention and treatment of obesity is important for the management of PCOS. This might be why we see so many studies conducted on weight loss.

Dietary interventions for women with PCOS:

A study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition looked at the difference between a high-protein diet (>40% of calories coming from protein; 30% fat; 30% carbohydrate) and a standard protein diet consisting of (<15% protein; 30% fat; 55% carbohydrate). There were 57 women with PCOS enrolled in the study, but only 27 women completed the study after the 6 month period. The women were not asked to limit calories, but were told to exercise 30 minutes a day. The high-protein diet resulted in greater weight loss, waist circumference and decreases in blood glucose than the standard protein diet. Women eating the standard protein group still lost weight (-7 lbs.) just not as much as the high protein group (-17 lbs.), but interestingly they had significantly lower testosterone levels than the high protein group (after adjusting for weight loss). When you look at the diets recommended and actual intake of nutrients there were no differences in saturated fat or fiber intake. In fact, as you’ll see from many of these studies researches are trying to keep total fat constant so they can measure the differences in biomarkers from different diets and see what works. Anyway, the high-protein groups were asked to avoid sugar and starchy carbohydrates and replace those foods with vegetables, fruit, nuts, and more protein from meat, eggs, fish, and dairy products. Beans and legumes were discouraged as protein sources because of their higher carbohydrate content. This is true, but beans still have a low-glycemic index so it was interesting the diet was designed as such. Just shows they really wanted to make sure folks were eating high protein and low carb. Both groups were advised to limit intakes of sweets, cakes and soft drinks and consume 6 servings of fruits and vegetables a day. Although this study found a higher protein diet was better for weight loss and glucose control versus the standard protein diet perhaps the lower levels of testosterone seen in women eating a standard protein diet are relevant. When we look at a similar study with the same type of design comparing high protein diets (HP: 30% protein, 40% carbohydrate, and 30% fat) with high carbohydrate diets (HC: 15% protein, 55% carbohydrate, and 30% fat) researchers found similar results. This time women were asked to restrict their calories by 1,000 kcals. After one month weight loss occurred in both groups, but there were no differences between the groups (about -4.0 kg ) . There and there were no statistical differences between the groups in circulating androgens or glucose levels, but when both groups were studied together circulating androgens and insulin sensitivity measurements did improve. There was no increased benefit to a high-protein diet.

A dietary intervention on obese women with PCOS compared two different diets on weight loss. Women were randomized to either a low-glycemic vegan diet or a low-calorie weight loss diet for 6 months. The vegan group lost significantly more weight at 3 months, but not at 6 months. Interesting the vegan group consumed even less calories (almost 300 kcal’s less) than the low-calorie dieters after 6 months.

Meta-analyses take into account several intervention studies at once, which can be very helpful. This meta-analysis tracked diet and exercise interventions on different sex hormones. Both interventions were found to offer significant improvements in hirsutism, and improved levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), total testosterone, androstenedione, and free androgen index (FAI) – a useful measure of the testosterone/SHBG ratio. All of these hormones play a role in PCOS. It is unclear exactly what foods were eaten in the dietary interventions, but in general the groups reduced daily caloric intake by roughly 500 calories and shot for macronutrient percentages of 50% carbohydrate, 30% fat, 20% protein. Exercise programs varied per study group as well , but in general 30 minutes of moderate exercise (walking, biking, aerobics) daily was recommended, but not always monitored. I think it is important to list the lifestyle methods performed as they do not seem drastic, however, the results were significant and note worthy.

Lastly, different diets were compared in this review. The most impactful was a low-glycemic diet, improving menstrual regularity and reducing insulin resistance, fibrinogen (a clotting factor), and cholesterol, while also improving quality of life. A low-carb diet seemed to help for some of these factors as well, including weight loss. A high-carbohydrate diet appeared to increased the free androgen index (which is a different conclusion than we saw before). The review concludes that all diets were helpful for weight loss and therefore should be a focus for all overweight women through reducing calories but making sure adequate nutrient intake and healthy foods are being consumed regardless of diet composition.

So what does this tell us? Well, it seems like diets for diabetes and heart disease prevention may also help women with PCOS. If controlling hormones and losing weight are some of the largest factors associated with PCOS, let’s look at some data comparing sex hormones and metabolic profiles between omnivores and vegetarians in pre- and post-menopausal women. Note that these women did not have PCOS, but this may help understand potential changes in sex hormones from certain dietary patterns. There were 62 women in the study. The vegetarians reported higher levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), bowel movements, and total fiber intake as well as lower levels of free estradiol, free testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-s) and BMI. After controlling for BMI (to make sure weight was not a factor on other variables) these changes were still significant. Researches concluded the rise in SHBG could be explained by the higher fiber intake and may explain the lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Another study that looked at the ability of diet to reduce bioavailable sex hormones included 104 healthy postmenopausal women with high testosterone levels. Researchers tracked changes in testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) over 4.5 months. Intense dietary counseling was performed. These women even had specially prepared group meals twice a week! The diet was designed to reduce insulin resistance: low in animal fat and refined carbohydrates and rich in low-glycemic-index foods, monounsaturated and omega-3 (polyunsaturated) fatty acids, and phytoestrogens. Women in the intervention group significantly boosted levels of SHBG while decreasing serum testosterone, compared to women who made no dietary changes. Furthermore, the intervention group significantly decreased body weight, waist:hip ratio, total cholesterol, fasting glucose level, and insulin resistance. The authors concluded that increased phytoestrogen intake decreases the bioavailability of serum sex hormones in hyperandrogenic postmenopausal women.

About DHEA and PCOS:

It is not clear the role of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on PCOS risk, however, since 20-30% of women experience excess androgen production it seems super important to research! DHEA serves as a good biomarker for androgen production. Therefore, DHEA may help researchers as they explore how certain foods or dietary patterns may help lower DHEA. One study found DHEA could be lowered by exercise and diet. Women with PCOS either followed a calorie restricted diet (35% protein, 45% carbohydrate and 20% fat), or an exercise program for 24 weeks. At the end of the study both interventions seems to help lower DHEA.

Reminder about medication and PCOS:

Check with your doctor about medications like metformin, as it has been studied extensively for the treatment of PCOS with positive results. Since medications come with side-effects it is important to weight the risks vs. benefits with your healthcare team. Often with PCOS you’ll find both medication and lifestyle intervention(diet and exercise) can be most effective. Perhaps if lifestyle is going so well that you are seeing improvements than tapering off the medication can be achieved? Interestingly, a few studies give hope that dietary changes may control PCOS as well as metformin. (Please keep in mind this may not always be the case and a few published studies does not justify avoiding potentially needed medications). Regardless, this study randomized 46 overweight women with PCOS to either a diet consisting of 1200-1400 kcal/day diet (25% proteins, 25% fat, and 50% carbohydrates plus 25-30 gm of fiber per week) or to take metformin for 6 months. Both groups had significant improvements in menstrual cycles, reductions in BMI, and luteinizing hormone levels and androgen (testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate) concentrations. One method did not seem to be better than the other. Clinical outcomes such as menstrual cycle patterns, ovulation, and pregnancy rates were also similar in both groups. This suggests high insulin and androgen hormone levels may be improved by diet or metformin. A second study looked at women with PCOS either eating a similar low calorie diet vs taking metformin for 12 weeks. Weight loss was seen in both treatments, but the diet group in this case was more effective in improving insulin resistance in the overweight and obese women. This study also looked at CRP levels and found both groups significantly lowered levels. This may be proof that diet works like metformin, which gives hope there is options for PCOS treatment. Still we need longer term follow up studies to see how these women are doing years after the experiment. Have the stuck to their diets? Did they end up needing medication? And what exactly were the participants eating and how could their diets improve? Lastly, Dr. Greger has a video presenting a study where lifestyle intervention reduced diabetes incidence by 58 percent, compared to only 31 percent with the drug. The lifestyle intervention was significantly more effective than the drug, and had fewer side-effects.

What about exercise and PCOS?

Many of the studies recommended about 30 minutes of exercise a day so perhaps the combination of diet and exercise has better results. That said, some studies did isolate diet alone (or rather did not tell participants to change exercise patterns) and exercise alone has been shown to help women with PCOS. My advice would be do both! Why perform one without the other as it would seem together diet and exercise can be more powerful. Obviously if limited in either capacity do what you can. I believe when dealing with any disorder mindfulness is important as well as social support and stress reduction techniques.

Dietary supplements and herbs for PCOS:

Marjoram is an herb that has been found to reduce DHEA and insulin levels in women with PCOS.

Dr. Greger mentions this study on spearmint in women with PCOS showing in just 5 days women were able to drop their free and total testosterone levels by about 30% drinking two cups of tea a day. I am unsure about mint and safety, check with your doctor if on medications with specific food interactions. To my knowledge mint should be safe for women with PCOS.

Maca root may be used to improve sexual function. In a petri dish there appears to be antioxidant activity. There seems to be limited data on concerns with psychological symptoms from taking maca. In other research, men taking maca had better health scores and significantly lowered an inflammatory marker, IL-6, known to increase cancer risk. It’s been traditionally consumed for nutritional and medicinal properties, but I am unsure how much is deemed unsafe. I did not see any research on maca and masculinity or heart palpitations. (If anyone find’s any or has more to add please add the research citation in the comments section). Again, I would speak with your doctor about their recommendations for usage. Visit our site on women’s health for more information that correlates with metabolic syndrome.

Lastly, there is some research that suggests supplements like magnesium, n-acetylcysteine, cinnamon, alpha-lipoic acid and/or omega-3 fatty acids may modulate factors associated with insulin sensitivity, thereby helping women with PCOS. One article in Today’s Dietitian mentions these supplements and other research on PCOS.

In Summary:

Weight loss is an important factor for PCOS as we see in study after study. I think overweight women need to find the best route of weight loss that works for them. I do not think calorie restriction is needed to loss weight. A high fiber diet low in the glycemic index seems to offer the best solutions. You would think with all this research an optimal diet could be recommended. I mean even this study titled “The optimal diet for women with PCOS?” fails to confirm the best approach. What is helpful about this study (and all the others referenced here) is that it provides awareness about dietary trends. Since women with PCOS are at greater risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease any diet that promotes weight loss and glycemic control may be beneficial. One interesting note is that most studies are performed on calorie restriction rather than dietary composition. The authors conclude a diet low in saturated fats and high in fiber from low-gycemic index foods are recommended.

My dietary suggestions for women with PCOS:

– Boost fiber intake to help modulate hormones and lower circulating testosterone

– Promote weight loss in overweight women

– Improve glycemic control and avoid developing diabetes

– Help manage symptoms like acne and hirsutism

– Focus on foods that help reduce inflammation

Of course, discuss these parameters with your healthcare team as dietary treatments are individualized. I highly recommend utilizing a registered dietitian for personal dietary advice.

For more information to help achieve these dietary suggestions:

DIABETES AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

Image Credit: Eduardo García Cruz / flicker