For perhaps 99.99 percent of our time as a species on Earth, we lived outdoors in the natural environment. Might there be a health benefit to returning now and again, and surrounding ourselves with nature? That’s a question that urban planners have asked. “Are people living in greener areas healthier than people living in less green areas?” Should we put it in a park or another car park?

“In a greener environment, people report fewer symptoms of illness and have better perceived general health. Also, people’s mental health appears to be better”—and by a considerable amount. Indeed, “assuming a causal relation between greenspace and health, 10% more greenspace in the living environment leads to a decrease in the number of symptoms that is comparable with a decrease in age by 5 years.” That is a big assumption, though.

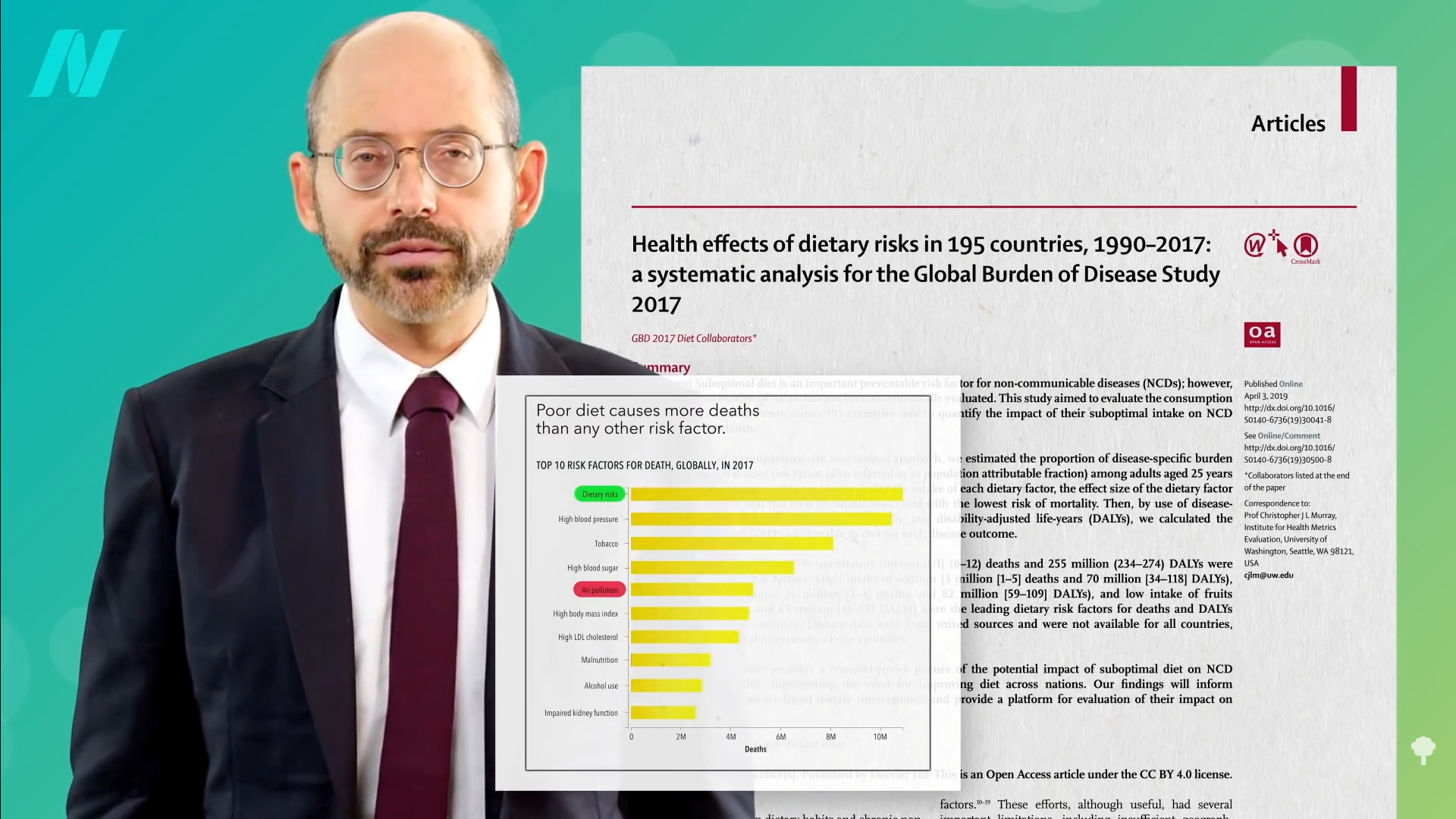

Still, you could imagine some potential mechanisms of why it could be. It could mean less air pollution, and air pollution is no joke. It is the fifth leading cause of death on our planet, killing about five million people a year. Though, of course, our number one risk factor is our diet, which kills twice as many individuals, as you can see below and at 1:18 in my video Are There Health Benefits of Spending Time in Nature?.

So, it could be an antipollution effect, or maybe there’s something special about experiencing greenspaces beyond them just offering more opportunities to exercise. The simplest explanation is probably that a natural setting “simply promotes health-enhancing behavior rather than having specific and direct benefits for health.” It’s harder to go jogging in the park when there is no park. Ironically, it seems that even when people have access to nature, they don’t necessarily take advantage of it. And, even if there were a link, “a question remains about the possibility of a ‘self-selection’ phenomenon: do natural environments elicit increased physical activity and well-being, or do physically active individuals choose to live in areas with more opportunities for physical activity?” What I wanted to know is, “apart from the promotion of physical activity,” are there “added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments”?

Now certainly, just being exposed to sunlight can treat things like seasonal affective disorder and provide vitamin D, the sunshine vitamin, but are there any other inherent benefits? You don’t know until you put it to the test. Some of the studies are just silly, though. Consider “Relationships Between Vegetation in Student Environments and Academic Achievement Across the Continental U.S.” At first, I thought the study was about academic achievement and vegetarianism, but no—it’s about vegetation. Researchers found a “positive relationship between non-forest vegetation and graduation rates for schools.” Maybe the Ivy League’s edge is from the ivy?

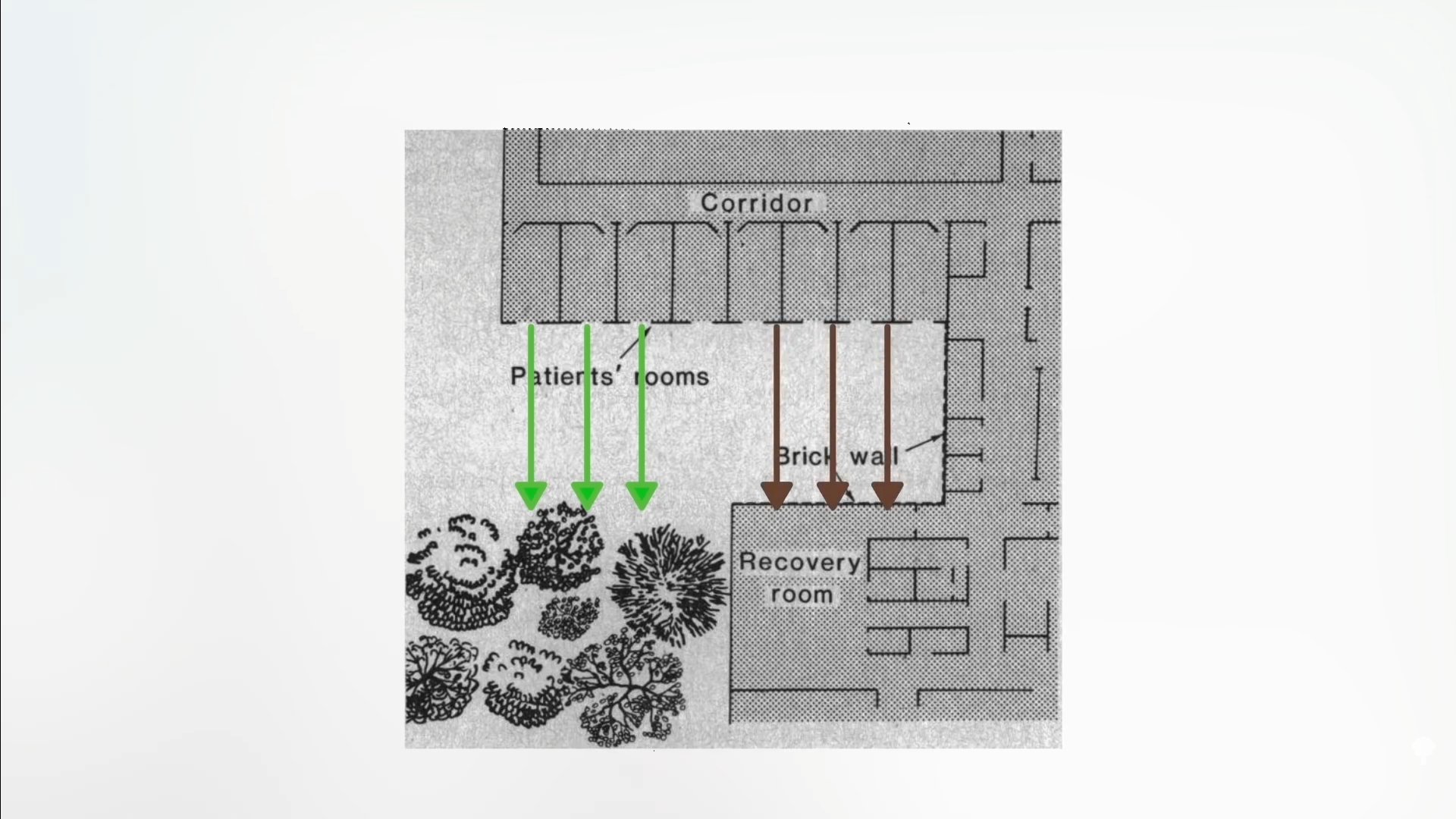

The study entitled “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery” starts to make things more interesting. As you can see below and at 3:04 in my video, some patient rooms at a suburban hospital looked out at trees, while others to a brick wall. “Twenty-three surgical patients assigned to rooms with windows looking out on a natural scene had shorter postoperative hospital stays…and took fewer potent analgesics [painkillers] than 23 matched patients in similar rooms with windows facing a brick building wall.” You can’t chalk that up to a vitamin D effect.

What could it be about just looking at trees? Maybe it is the “vitamin G”—just the color of green. We know how healthy it is to eat our greens. What about just looking at them? Researchers had people exercise while watching a video simulating going through a natural, green-colored setting, the same video in black and white, or everything tinted red, and no differences were noted (with the exception that red made people feel angry), as you can see below and at 3:46 in my video.

The most interesting mechanism that has been suggested that I’ve run across is fractals. Have you ever noticed that “for example, in a tree, all the branches—from big to small—are scaled-down versions of the entire tree”? Each branch has a shape similar to the whole tree itself. Fractal patterns are found throughout nature, where you see “a cascade of self-similar patterns over a range of magnification scales, building visual stimuli that are inherently complex.” And, as you can see when you’re hooked up to an EEG, our brain seems to like them, too.

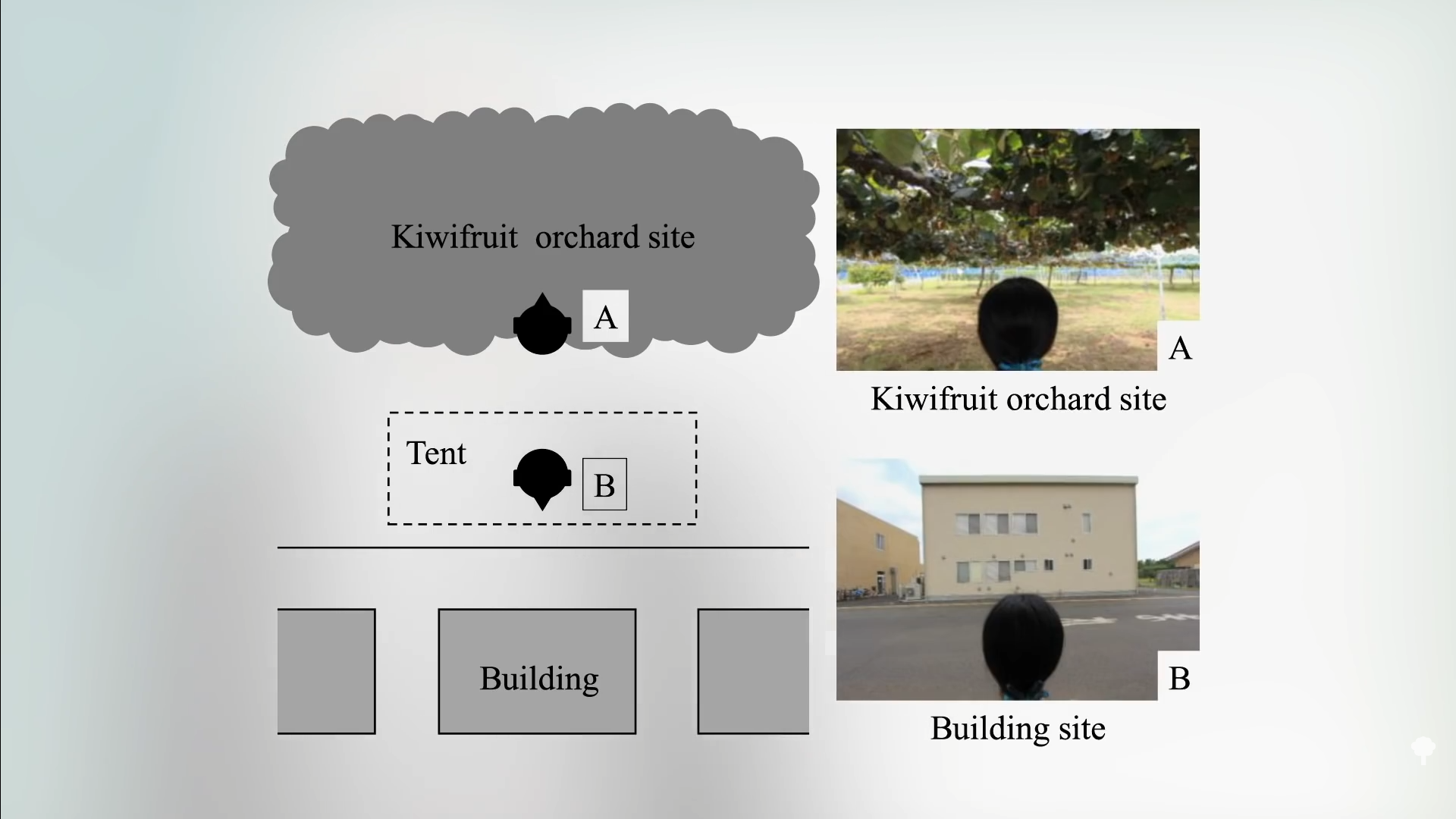

Regardless of the mechanism, if you compile all the controlled studies on using nature as a health promotion intervention, you tend to see mostly psychological benefits, whereas the findings related to physical outcomes were less consistent. “The most common type of study outcome was self-reported measures of different emotions.” For instance, what makes you feel better: staring at a kiwifruit orchard or a building? (See below and 4:41 in my video.) Awkwardly described, thanks presumably to the language barrier, as a comparison of “synthetic versus organic stimulation.”

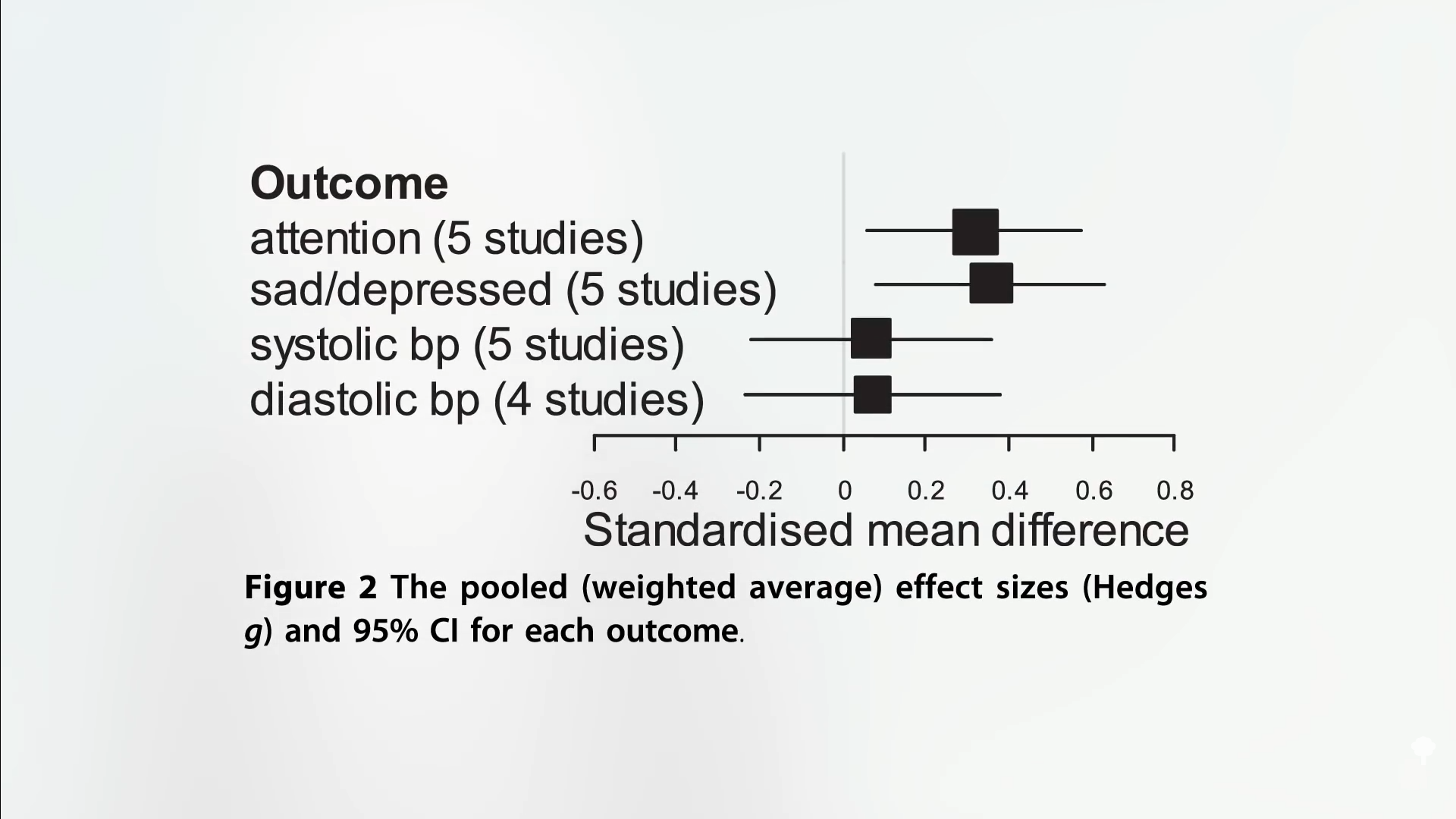

As you can see below and at 5:00 in my video, natural settings may make people more attentive and less sad, but when it comes to some objective measures like blood pressure, no significant effect was found. People who exercise outdoors often say they feel great, “suggesting that green exercise activities can increase…various psychological subscales,” such as “mood, focus, and energy”—within just five or so minutes of being out in the woods.

Yet these studies tended not to be randomized trials. Researchers just asked people who already sought out nature what they thought about nature, so it’s no wonder they like it—otherwise, they wouldn’t be out there. But nature-based interventions are low-cost, often free, in fact, and non-invasive (unless you count the mosquitoes). So, if you want “a natural high,” I say go for it, whatever makes you happy. (Not all green exercisers like trees. Golfers just viewed them as obstacles.)

For more on air pollution, see my videos Best Food to Counter the Effects of Air Pollution and The Role of Pesticides and Pollution in Autism.

Of course, there are benefits to any kind of exercise indoors or out. Check out the related posts below.