The book Dieting Makes You Fat was published originally in the 1980s and then repeatedly republished. Since most people who lose weight go on to regain it, there is a concern that there may be adverse health consequences of “yo-yo dieting.” This idea emerged from animal studies that, for example, showed the detrimental effects of starving and refeeding obese rats. This captured the media’s attention, leading to “a pervasive view found in many media outlets” about “the ‘dangers’ of weight cycling,” discouraging people from even trying to lose weight.

But even the animal data are inconclusive. For example, weight-cycling mice make them live longer. Most importantly, a review of the human data concluded that “evidence for an adverse effect of weight cycling appears sparse if it exists at all.” Bottom line? “Yo-Yo Dieting Is Better than None.”

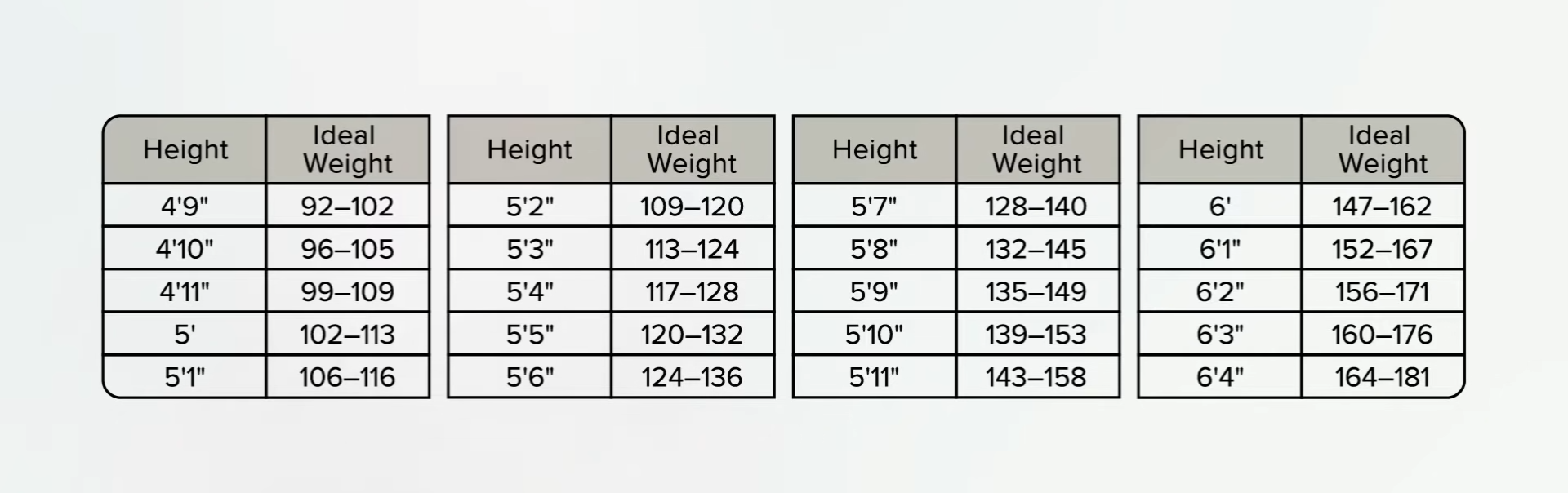

Ideally, we’d be at a body mass index (BMI) of 20 to 22. (You can see a unisex BMI chart below and at 1:05 of my video What’s the Ideal Waist Size?.) However, BMI doesn’t take into account the composition of the weight. Bodybuilders are heavy for their height, for instance, yet can be extremely lean. The gold standard measure of obesity is body fat percentage, but an accurate calculation can be complicated and expensive. All you need to measure BMI is height and weight, but it may underestimate the true prevalence of obesity.

The World Health Organization defines obesity as a body fat percentage above 25 percent in men or 35 percent in women. At a BMI of 25, which is considered just barely overweight, body fat percentages in a representative sample of U.S. adults varied from 14 percent to 35 percent in men and 26 to 43 percent in women. So, you could be at a “normal” weight but actually obese. Using the BMI cutoff for obesity, only about one in five Americans was obese in the 1990s, but based on their body fat, the true proportion even back then was closer to 50 percent. Half of Americans are not just overweight, but obese.

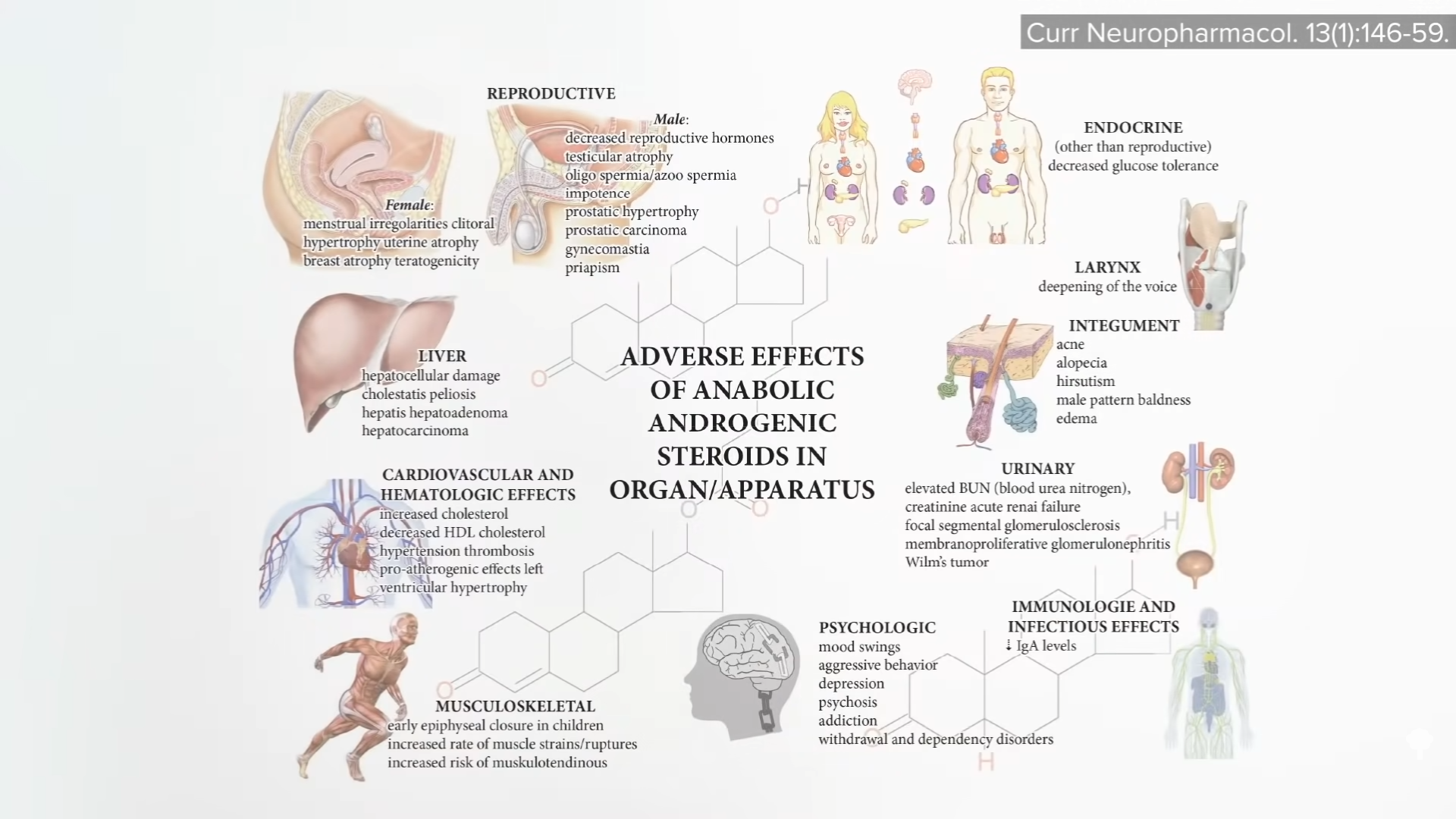

So, using only BMI, doctors may misclassify more than half “of patients with excess body fat as being normal or just overweight and…miss an opportunity to intervene and reduce health risk in such individuals.” What’s important is not the label, though, but the health consequences. Ironically, BMI appears to be an even better predictor of cardiovascular disease death than body fat percentage. That suggests that excess weight from any source—whether fat or lean—may not be healthy in the long run. The lifespan of bodybuilders does seem to be cut short. They have about a one-third higher mortality rate than the general population. The average age of death is around 48 years, but this may be due in part to the toxic effects of anabolic steroids on the heart, as shown below and at 2:57 in my video.

Pre-eminent nutritional physiologist Ancel Keys (after which “K-rations” were named) suggested the mirror method: “If you really want to know whether you are obese, just undress and look at yourself in the mirror. Don’t worry about our fancy laboratory measurements; you’ll know!” All fat is not the same, though. There is the pinchable superficial flab that we may see jiggling about our body, and then there’s the riskier, deeper visceral fat that coils around and infiltrates our internal organs. Measuring BMI is simple, cheap, and effective, but it does not take into account the distribution of fat on the body, whereas waist circumference can provide a measure of the deep underlying belly fat.

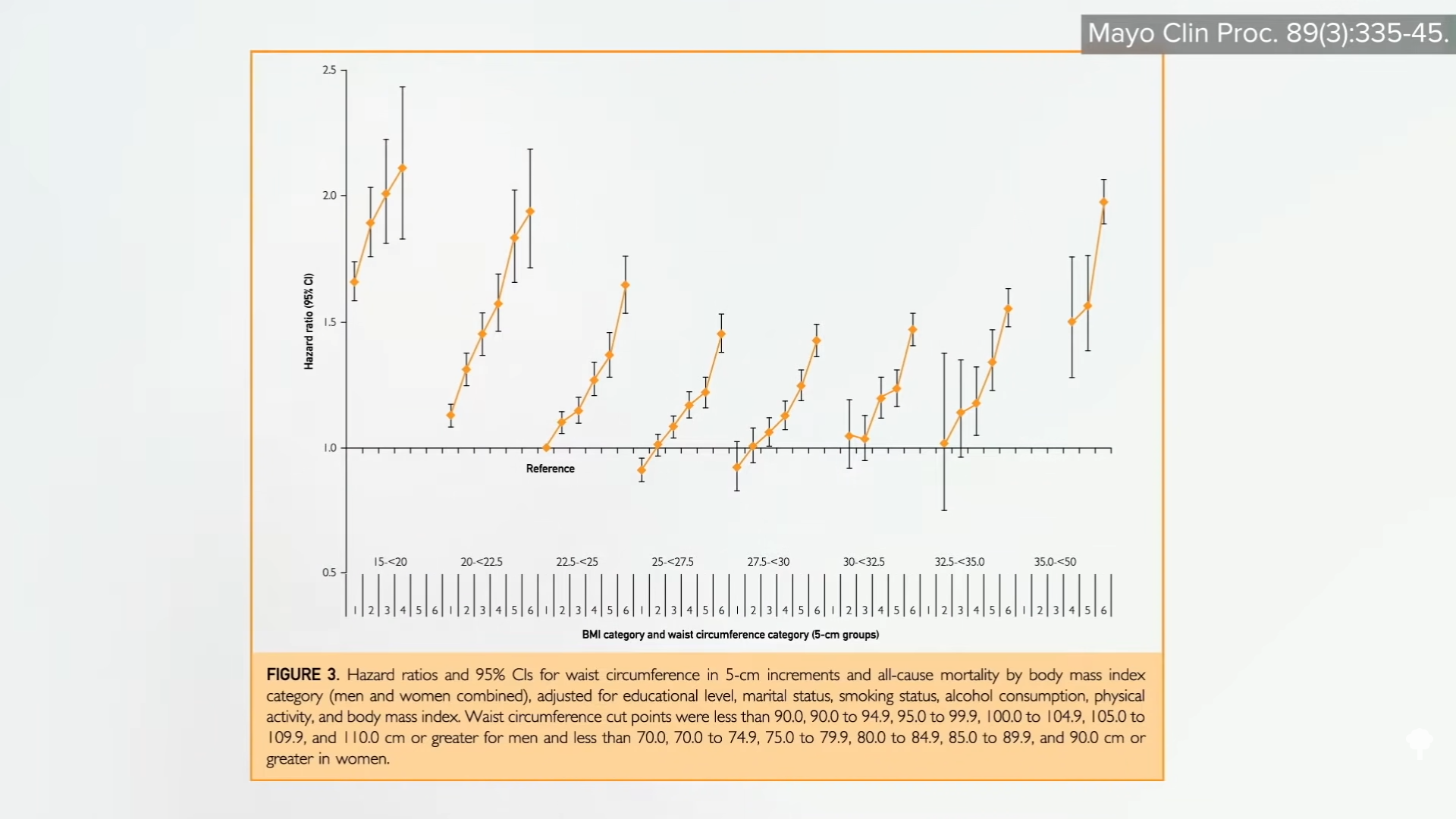

Both BMI and waist circumference can be used to predict the risk of death due to excess body fat, but, as you can see below and at 3:53 in my video, even at the same BMI, there appears to be nearly a straight-line increase in mortality risk with widening waistlines. Someone who has “normal-weight central obesity”—meaning someone who isn’t overweight, according to their BMI, but is fat around the middle—may have up to twice the risk of dying compared to someone who is obese, according to their height and weight. This is why the current guidance recommends measuring both BMI and waist circumference. This may be especially important for older women. “Between the ages of 25 and 65, the average woman will lose approximately 13 pounds of bone and muscle mass, while her visceral fat will nearly quadruple in size….” (Men tend to only double their visceral fat.) So, even if a woman doesn’t gain any weight according to the bathroom scale, she may be gaining fat.

What is the waistline cut-off? Increased risk of metabolic complications starts at an abdominal circumference of 31.5 inches (80 cm) in women and 37 inches (94 cm) in most men, though it is closer to 35.5 inches (90 cm) for South Asian, Chinese, and Japanese men. The benchmark for substantially increased risk starts at about 34.5 inches (88 cm) for women and 40 inches (102 cm) for men. Once you get above an abdominal circumference of about 43 inches (110 cm) in men, mortality rates shoot up about 50 percent compared to men with 8-inch-smaller (20-cm-smaller) stomachs, and women suffer 80 percent greater mortality risk with waists of 37.5 inches (95 cm) compared to 27.5 inches (70 cm). The reading of a measuring tape may translate into years of one’s lifespan.

The good news is the riskiest fat is the easiest to lose. Our body appears smart enough to preferentially shed the villainous visceral fat first. Although it may take losing as much as 20 percent of our weight to realize significant improvements in quality of life for most individuals with severe obesity, disease risk drops almost immediately. At 3 percent weight loss, which is only 6 pounds (2.7 kg) for someone weighing 200 pounds (91 kg), for instance, blood sugar control and triglycerides start to improve. At 5 percent, blood pressure and cholesterol improve. Our risk of developing diabetes may be cut in half by just a 5 percent weight loss, about 10 pounds (4.5 kg) for someone starting at 200 pounds (91 kg), for instance.

This is the final video in this series on obesity and weight. If you missed any of the others, see related posts below.

I cover all of this and more at length in my book How Not to Diet, and its companion, The How Not to Diet Cookbook, has more than 100 delicious Green-Light recipes that incorporate some of my 21 Tweaks for the acceleration of body fat loss.