What is the dirty little secret of drugs for lifestyle diseases?

Drug companies go out of their way—in direct-to-consumer ads, for example—to “present pharmaceutical drugs as a preferred solution to cholesterol management while downplaying lifestyle change.” You see this echoed in the medical literature, as in this editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association: “Despite decades of exhortation for improvement, the high prevalence of poor lifestyle behaviors leading to elevated cardiovascular disease risk factors persists, with myocardial infarction [heart attack] and stroke remaining the leading causes of death in the United States. Clearly, many more adults could benefit from…statins for primary prevention.” Do we really need to put more people on drugs? A reply was published in the British Medical Journal: “Once again, doctors are implored to ‘get real’—stop hoping that efforts to help their patients and communities adopt healthy lifestyle habits will succeed, and start prescribing more statins. This is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Note that the author of these comments [the pro-statin editorial] disclosed receipt of funding from 11 drug companies, at least four of which produce or are developing new classes of cholesterol-lowering agents,” which make billions of dollars a year in annual sales.

Every time the cholesterol guidelines expand the number of people eligible for statins, they’re decried as a “big kiss to big pharma.” This is understandable, since the majority of guideline panel members “had industry ties,” financial conflicts of interest. But these days, all the major statins are off-patent, so there are inexpensive generic versions. For example, the safest, most effective statin is generic Lipitor, sold as atorvastatin for as little as a few dollars a month. So, nowadays, the cholesterol guidelines are not necessarily “part of an industry plot.”

“The US way of life is the problem, not the guidelines…” The reason so many people are candidates for cholesterol- and blood-pressure-lowering medications is that so many people are taking such terrible care of themselves. The bottom line is that “individuals must take more responsibility for their own health behaviors.” What if you are unwilling or unable to improve your diet and make lifestyle changes to bring down that risk? If your ten-year risk of having a heart attack is 7.5 percent or more and going to stay that way, then the benefits of taking a statin drug likely outweigh the risk. That’s really for you to decide, though. It’s your body, your choice.

“Whether or not the overall benefit-harm balance justifies the use of a medication for an individual patient cannot be determined by a guidelines committee, a health care system, or even the attending physician. Instead, it is the individual patient who has a fundamental right to decide whether or not taking a drug is worthwhile.” This was recognized by some of medicine’s “historical luminaries such as Hippocrates,” but “only in recent decades has the medical profession begun to shift from a paternalistic ‘doctor knows best’ stance towards one explicitly endorsing patient-centered, evidence-based, shared decision-making.” One of the problems with communicating statin evidence to support this shared decision-making is that most doctors “have a poor understanding of concepts of risk and probability and…increasing exposure to statistics in undergraduate and postgraduate education hasn’t made much difference.” But that understanding is critical for preventive medicine. When doctors offer a cholesterol-lowering drug, “they’re doing something quite different from treating a patient who has sought help because she is sick. They’re not so much doctors as life insurance salespeople, peddling deferred benefits in exchange for a small (but certainly not negligible) ongoing inconvenience and cost. In this new kind of medicine, not understanding risk is the equivalent of not knowing about the circulation of the blood or basic anatomy. So, let’s dive in and see exactly what’s at stake.

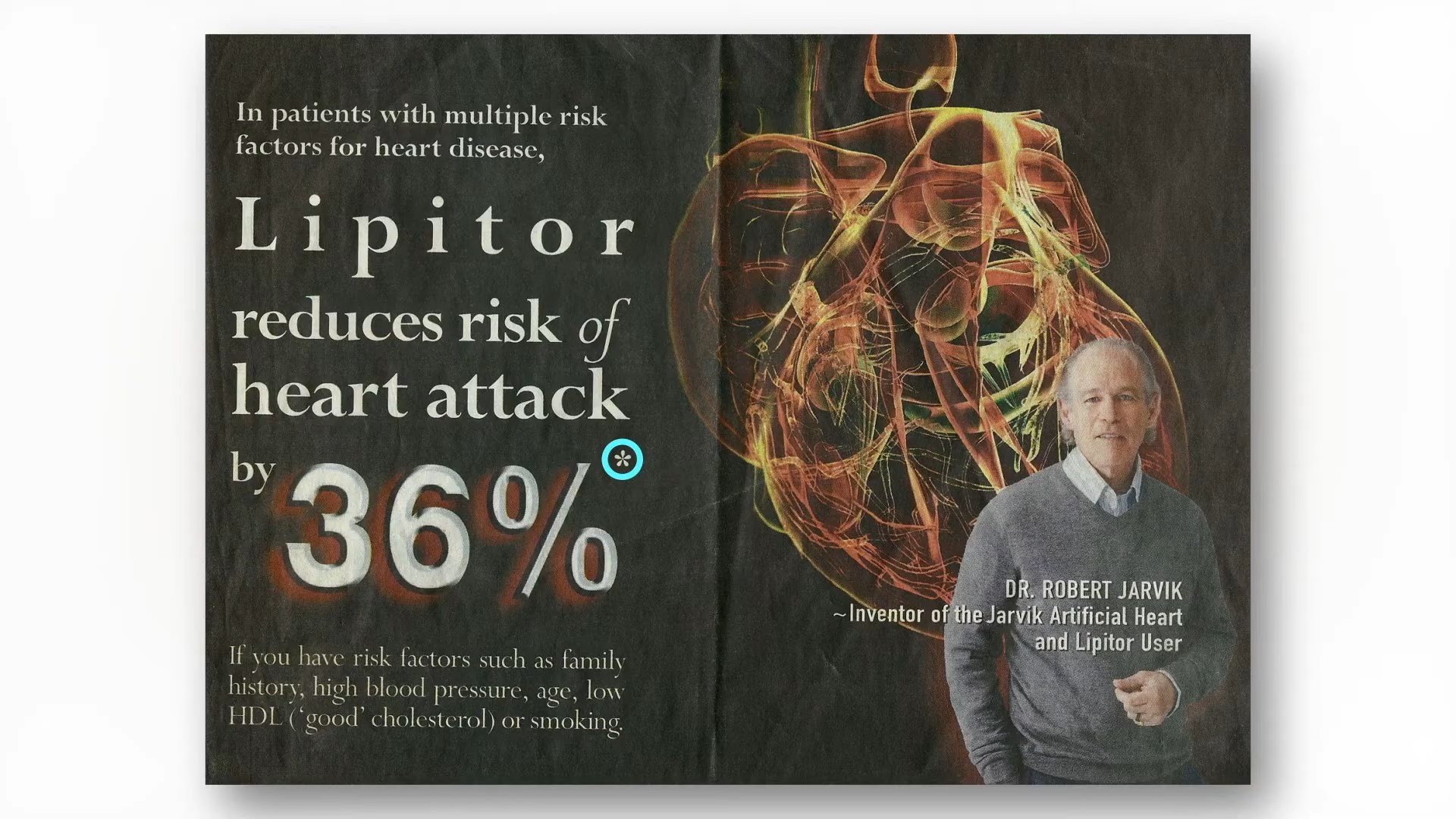

Below and at 3:55 in my video Are Doctors Misleading Patients About Statin Risks and Benefits? is an ad for Lipitor. When drug companies say a statin reduces the risk of a heart attack by 36 percent, that’s the relative risk.

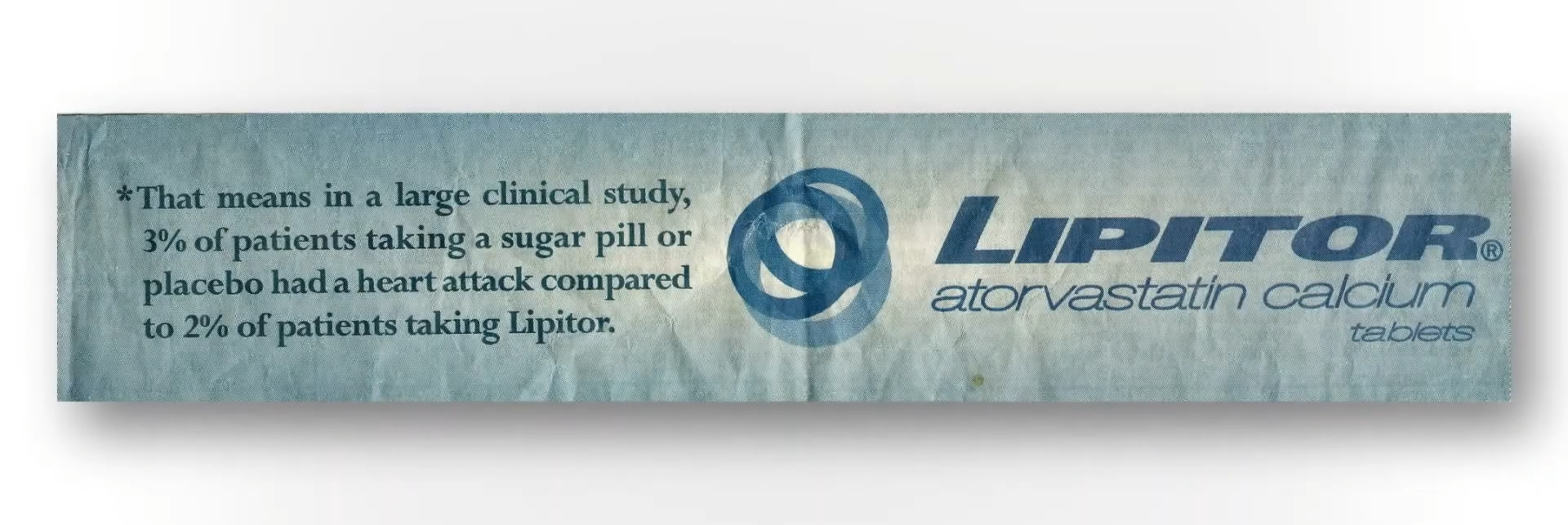

If you follow the asterisk I’ve circled after the “36%” in the ad, you can see how they came up with that. I’ve included it here and at 3:56 in my video. In a large clinical study, 3 percent of patients not taking the statin had a heart attack within a certain amount of time, compared to 2 percent of patients who did take the drug. So, the drug dropped heart attack risk from 3 percent to 2 percent; that’s about a one-third drop, hence the 36 percent reduced relative risk statistic. But another way to look at going from 3 percent to 2 percent is that the absolute risk only dropped by 1 percent. So, in effect, “your chance to avoid a nonfatal heart attack during the next 2 years is about 97% without treatment, but you can increase it to about 98% by taking a Crestor [a statin] every day.” Another way to say that is that you’d have to treat 100 people with the drug to prevent a single heart attack. That statistic may shock a lot of people.

If you ask patients what they’ve been led to believe, they don’t think the chance of avoiding a heart attack within a few years on statins is 1 in 100, but 1 in 2. “On average, it was believed that most patients (53.1%) using statins would avoid a heart attack after statin treatment for 5 years.” Most patients, not just 1 percent of patients. And this “disparity between actual and expected effect could be viewed as a dilemma. On the one hand, it is not ethically acceptable for caregivers to deliberately support and maintain illusive treatment expectations by patients.” We cannot mislead people into thinking a drug works better than it really does, but on the other hand, how else are we going to get people to take their pills?

When asked, people want an absolute risk reduction of at least about 30 percent to take a cholesterol-lowering drug every day, whereas the actual absolute risk reduction is only about 1 percent. So, the dirty little secret is that, if patients knew the truth about how little these drugs actually worked, almost no one would agree to take them. Doctors are either not educating their patients or actively misinforming them. Given that the majority of patients expect a much larger benefit from statins than they’d get, “there is a tension between the patient’s right to know about benefiting from a preventive drug and the likely reduction in uptake [willingness to take the drugs] if they are so informed,” and learn the truth. This sounds terribly paternalistic, but hundreds of thousands of lives may be at stake.

If patients were fully informed, people would die. About 20 million Americans are on statins. Even if the drugs saved 1 in 100, that could mean hundreds of thousands of lives lost if everyone stopped taking their statins. “It is ironic that informing patients about statins would increase the very outcomes they were designed to prevent.”