Oxidized cholesterol, which is concentrated in products containing eggs, processed meat, and parmesan cheese, has cancer-fueling estrogenic effects on human breast cancer.

In 1908, the presence of cholesterol crystals was noted “in the proliferating areas of cancers,” suggesting that cholesterol “may, in some way or other, be associated with the regulation of proliferation.” A century later, we now recognize that the “accumulation of cholesterol is a general feature of cancer tissue, and recent evidence suggests that cholesterol plays critical roles in the progression of cancers, including breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers.” I discuss this in my video Oxidized Cholesterol 27HC May Explain Three Breast Cancer Mysteries.

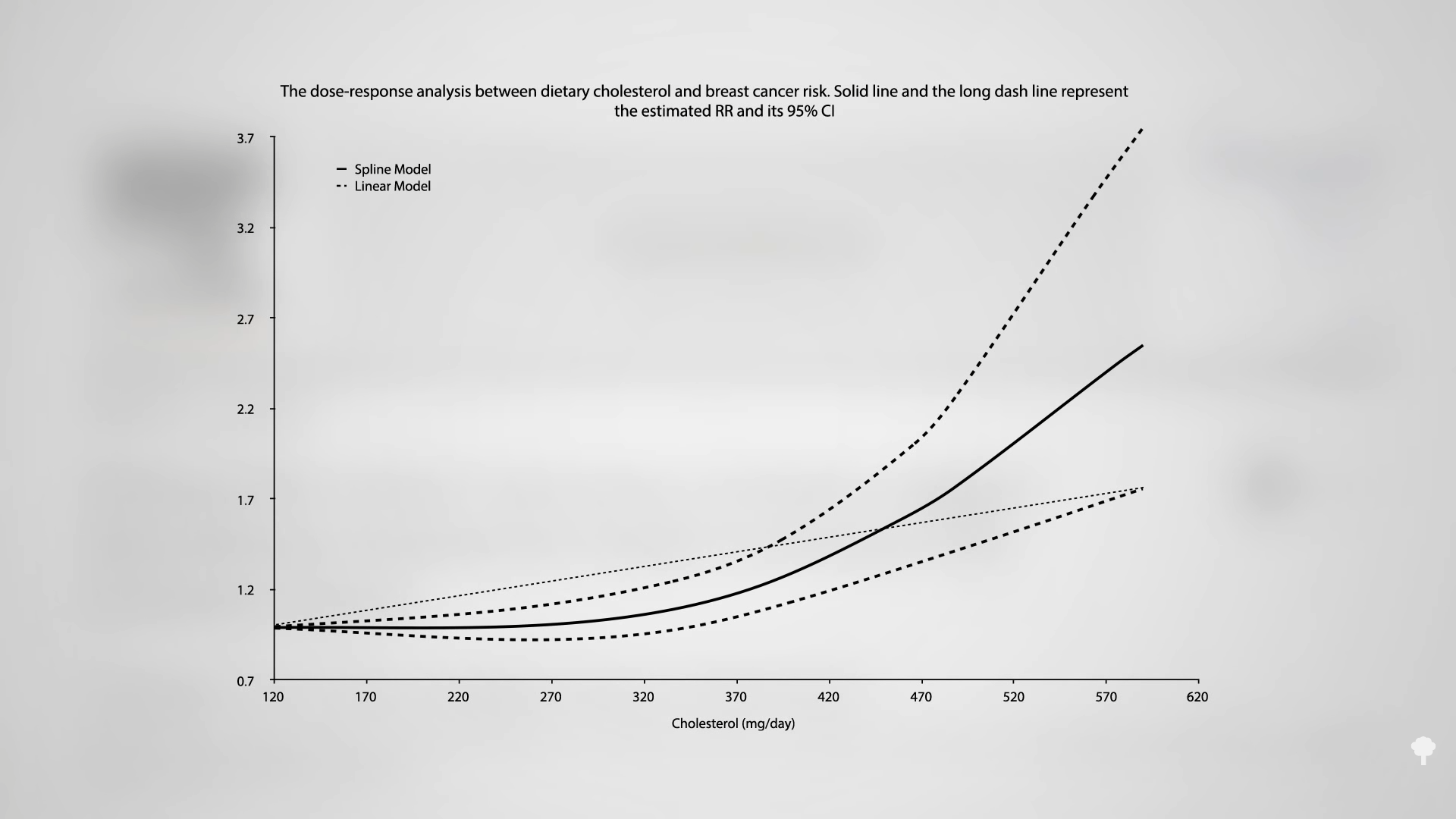

Might this explain why egg consumption is associated with increased risk of breast cancer? Indeed, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence “suggest that dietary cholesterol intake increases risk of breast cancer,” and the more cholesterol you eat, the higher the risk appears to rise, as you can see in the graph below and at 0:52 in my video. Why is that?

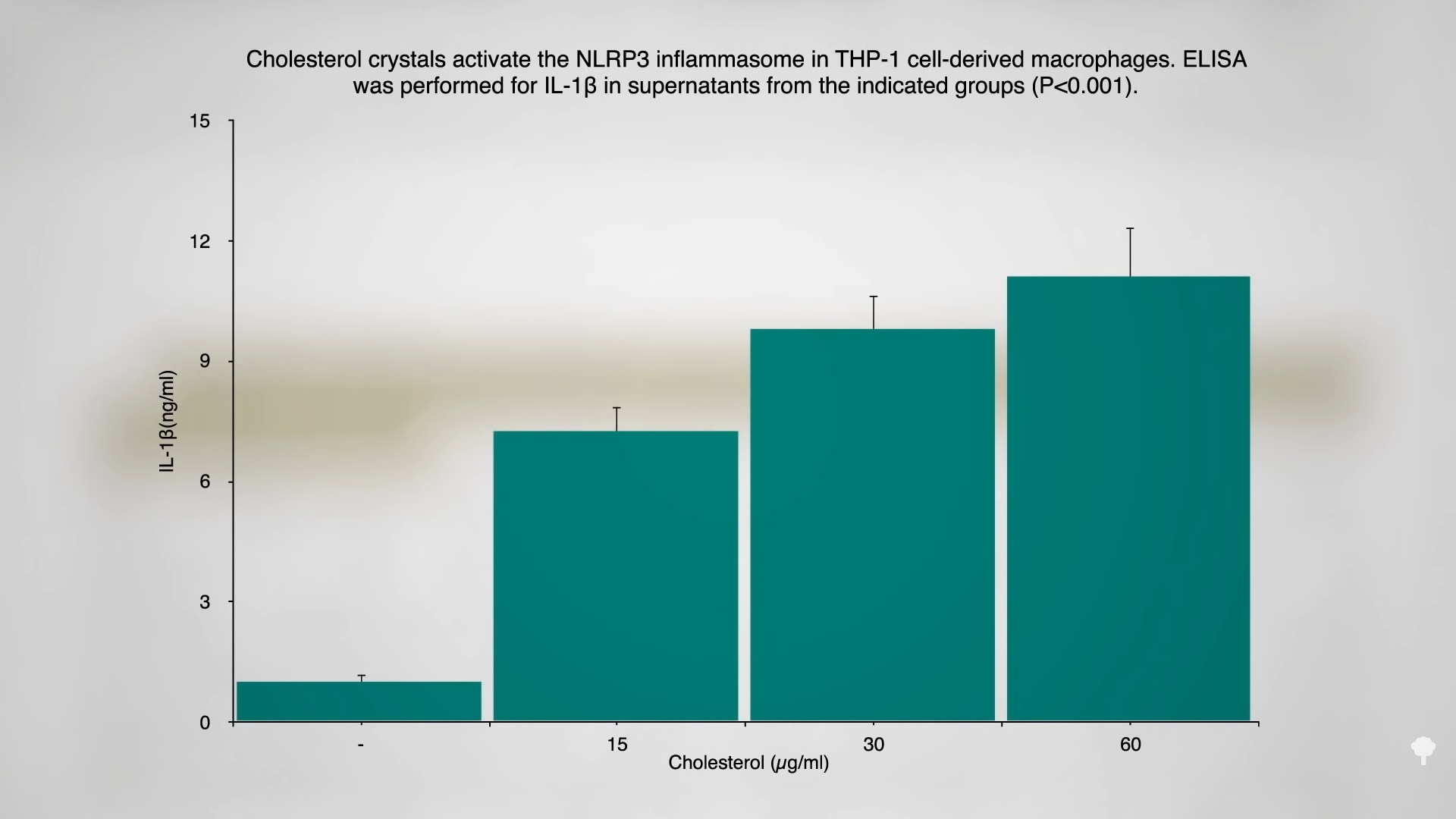

One thought is the “prolonged ingestion of a cholesterol-enriched diet induces chronic, auto-inflammatory responses resulting in significant health problems including colorectal cancer,” and we know that “chronic nonresolving inflammation leads to the initiation, promotion, and progression of tumor development.” As you can see in the graph below and at 1:12 in my video, sprinkling some cholesterol on white blood cells in a test tube can trigger the release of inflammatory compounds, and LDL cholesterol can induce breast cancer proliferation and invasion, but that’s in vitro. In a petri dish, you can show that breast cancer cells can migrate nearly twice as far within a day in the presence of LDL cholesterol, but what happens in people?

The level of LDL cholesterol in the blood of women diagnosed with breast cancer does appear to be a predictive factor of tumor progression. About two years after surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, not a single one of the women in the lowest third of LDL cholesterol levels had a cancer recurrence. The same could not be said for women with higher cholesterol. We know cholesterol can cause inflammation in our artery walls. Might it also have an effect on breast cancer initiation and progression? Researchers speculate that high cholesterol levels may have a “cancer-fuelling effect,” and, indeed, women with breast cancer who happen to be taking cholesterol-lowering statin drugs appear to live about 40 percent longer before the cancer comes back. The data aren’t good enough to ensure the drug benefits outweigh their risks, though. Lowering cholesterol with diet may be able to give us the best of both worlds.

Animal studies show that if you feed cholesterol to mice, you can accelerate their cancers, “but extrapolation to humans is difficult as dietary cholesterol has limited effect on blood cholesterol levels in humans.” Thus, dietary cholesterol might just be “indicative of a lifestyle prone to health-related problems, including cancer”—that is, maybe people are just more likely to have an after-meal cigarette if that meal is bacon and eggs compared to oatmeal. It was difficult to imagine how dietary cholesterol alone could promote cancer development, but that changed recently with the discovery that 27-hydroxycholesterol, “27HC, a metabolite of cholesterol, can function as an estrogen and increase the proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells.”

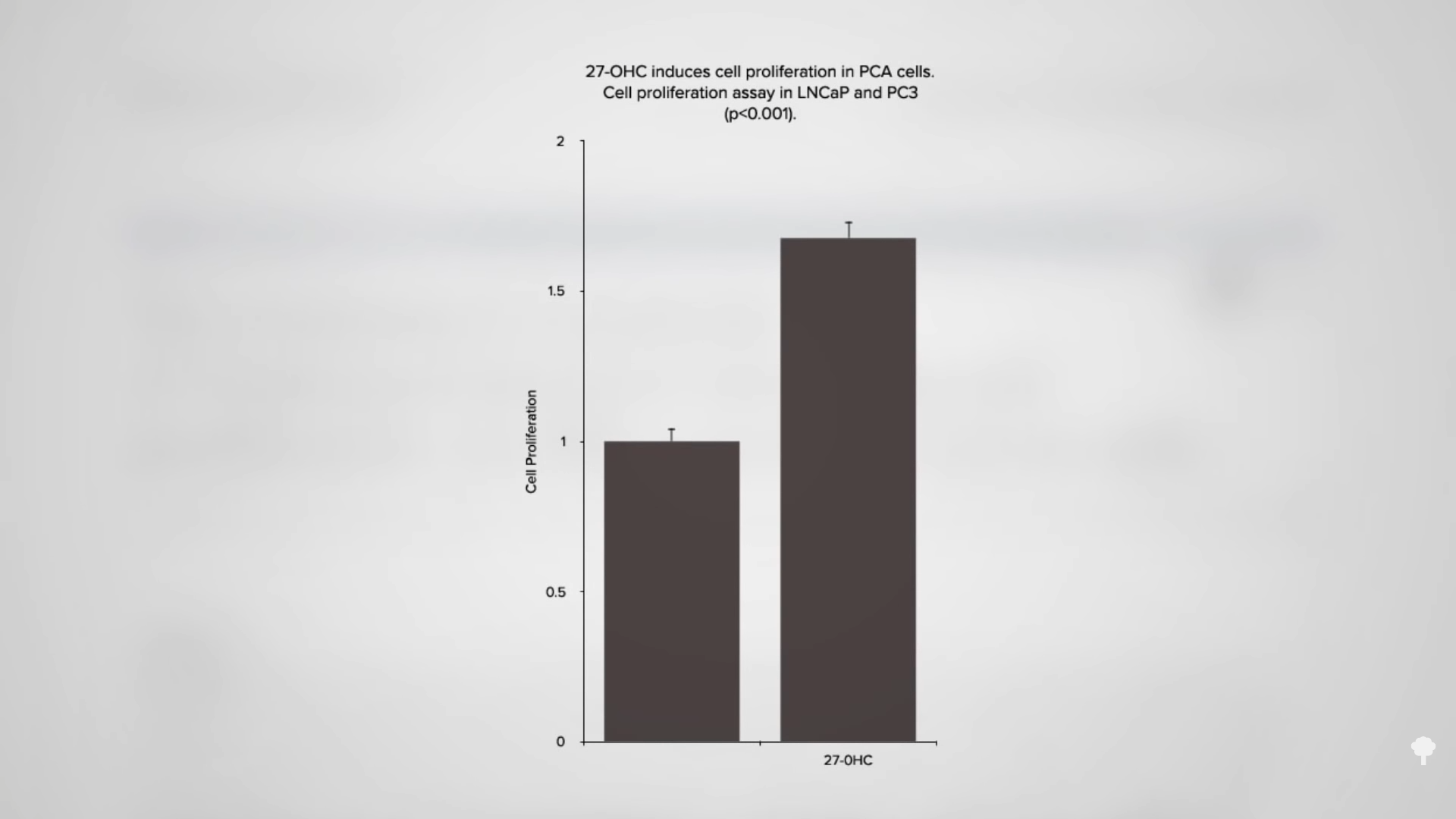

So, it’s not the cholesterol itself, but what the cholesterol turns into inside our body. “Scientists have long struggled to understand why women with heart disease risk factors are more likely to develop breast cancer.” Now, perhaps, we know. “The discovery that the most abundant cholesterol oxidized metabolite in the plasma,” in our bloodstream, can have estrogenic effects may explain the link between high cholesterol and the development and progression of breast cancer and prostate cancer. And, 27-hydroxycholesterol also stimulates the proliferation of prostate cancer cells, boosting growth by about 50 percent, as you can see in the graph below and at 3:58 in my video.

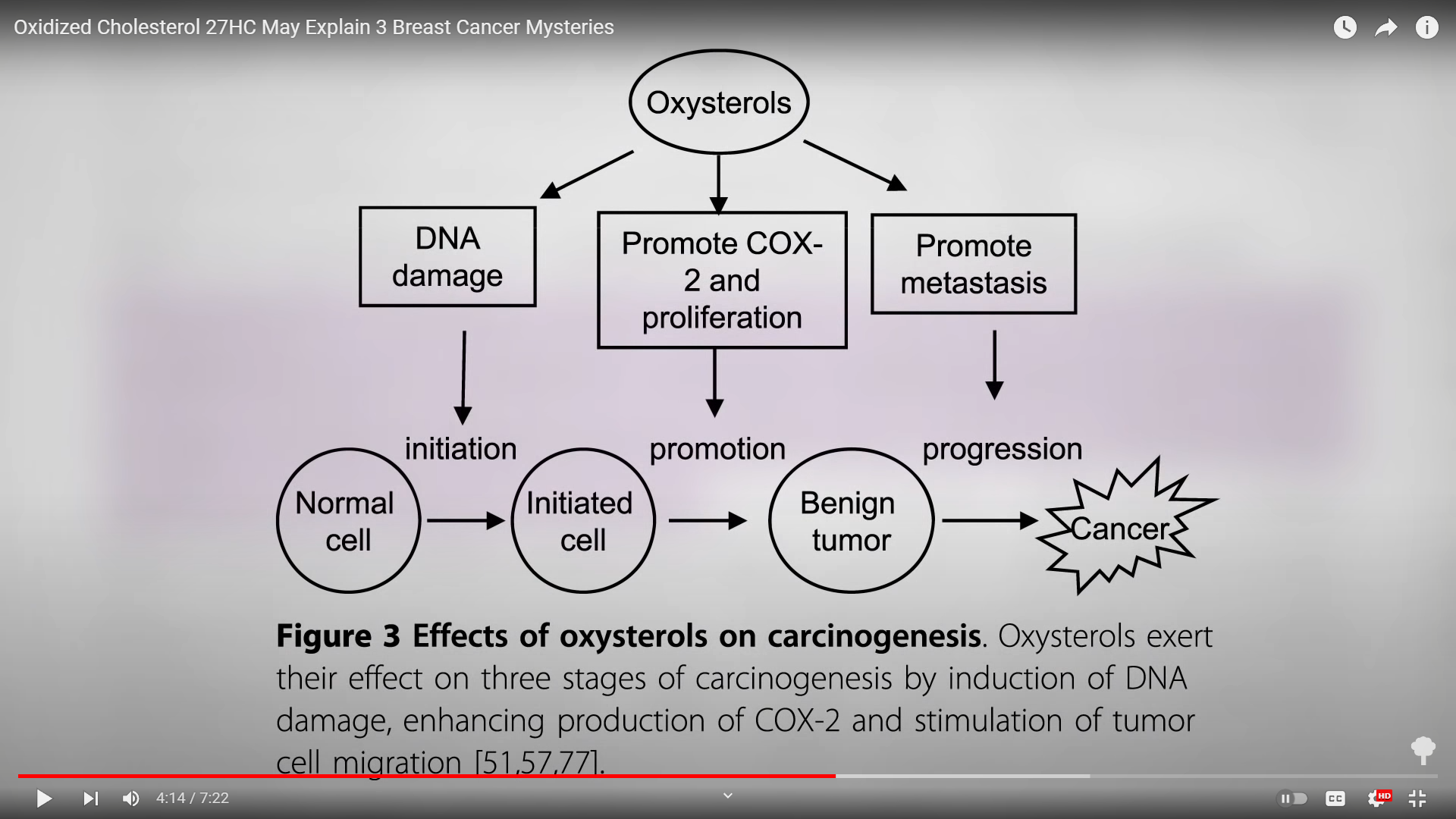

I’ve previously explored the “role for oxysterols in mediating pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory processes in age-related degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis,” heart disease, but it now looks like oxidized cholesterol can play a role in all three stages of tumor development, as well: initiation, promotion, and then the progression of the cancer, as you can see below and at 4:14 in my video. It doesn’t just promote the growth of breast cancer cells, but also “induces invasion and migration of breast cancer cells,” potentially facilitating breast cancer metastasis through suppressing anti-cancer immunity and then inducing angiogenesis, helping breast tumors hook up their blood supply.

“Several lines of evidence support a pathologic role” for this cholesterol metabolite. We know that when you feed cholesterol to mice, their oxysterol levels go up and their tumors accelerate, but it “also appears to dramatically hasten the spread, or metastasis, of breast tumors to other organs.” But, when researchers “turned to human breast tissue samples, they found that more aggressive tumors had higher levels of an enzyme…which converts cholesterol into 27HC.” In breast cancer patients with estrogen receptor-positive tumors, the 27-hydroxycholesterol content in their breast tissue is increased overall and especially within the tumor itself—so much so that circulating oxysterol levels in the blood may one day be used as a prognostic factor. And “breast cancer patients with low tumor levels of…[the] enzyme that breaks down 27HC…did not live as long as women with the highest levels” who can detoxify it better. “The bottom line…is that some estrogen-driven breast tumors may rely on 27HC to grow when estrogen isn’t available.” And that may explain a second breast cancer mystery.

More than 80 percent of breast cancers start out responding to estrogen, so we use hormone blockers—either aromatase inhibitors to stop the formation of estrogen in the first place or the drug tamoxifen to block its action. Despite the efficacy of these drugs, many patients relapse with resistant tumors, and that’s where oxidized cholesterol can come in. 27HC can fuel breast cancer growth without estrogen, which could explain why these estrogen blockers sometimes don’t work.

And, finally, 27HC may explain why breast cancer patients with higher vitamin D levels appear to live longer. Vitamin D supplementation decreases 27HC levels in the blood.

The best way to reduce our risk of getting breast cancer—and surviving it if we do get the diagnosis—may be to just lower our overall cholesterol. If you lower your cholesterol, you lower your oxidized cholesterol. So, discovering this role of cholesterol is actually really good news, since “cholesterol is a highly amenable risk factor, either by lifestyle, dietary, or pharmacologic interventions.” One of the implications of these findings, according to the principal investigator, is that “lowering cholesterol with dietary changes or statins [drugs] could reduce a women’s breast cancer risk or slow tumor growth.”

Since vitamin D supplementation decreases 27-HC levels in the blood, you may be interested in the best way get Vitamin D. See my videos The Best Way to Get Vitamin D: Sun, Supplements, or Salons? and The Risks and Benefits of Sensible Sun Exposure.