A randomized controlled trial investigates diet and psychological well-being.

“Psychological health can be broadly conceptualized as comprising 2 key components: mental health (i.e., the presence of absence of mental health disorders such as depression) and psychological well-being (i.e., a positive psychological state, which is more than the absence of a mental health disorder,” and that is the focus of an “emerging field of positive psychology [that] focuses on the positive facts of life, including happiness, life satisfaction, personal strengths, and flourishing.” This may translate to physical “benefits of enhanced well-being, including improvements in blood pressure, immune competence, longevity, career success, and satisfaction with personal relationships.”

What is “The Contribution of Food Consumption to Well-Being,” the title of an article in Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism? Studies have “linked the consumption of fruits and vegetables with enhanced well-being.” A systematic review of research found evidence that fruit and vegetable intake “was associated with increased psychological well-being.” Only an association?

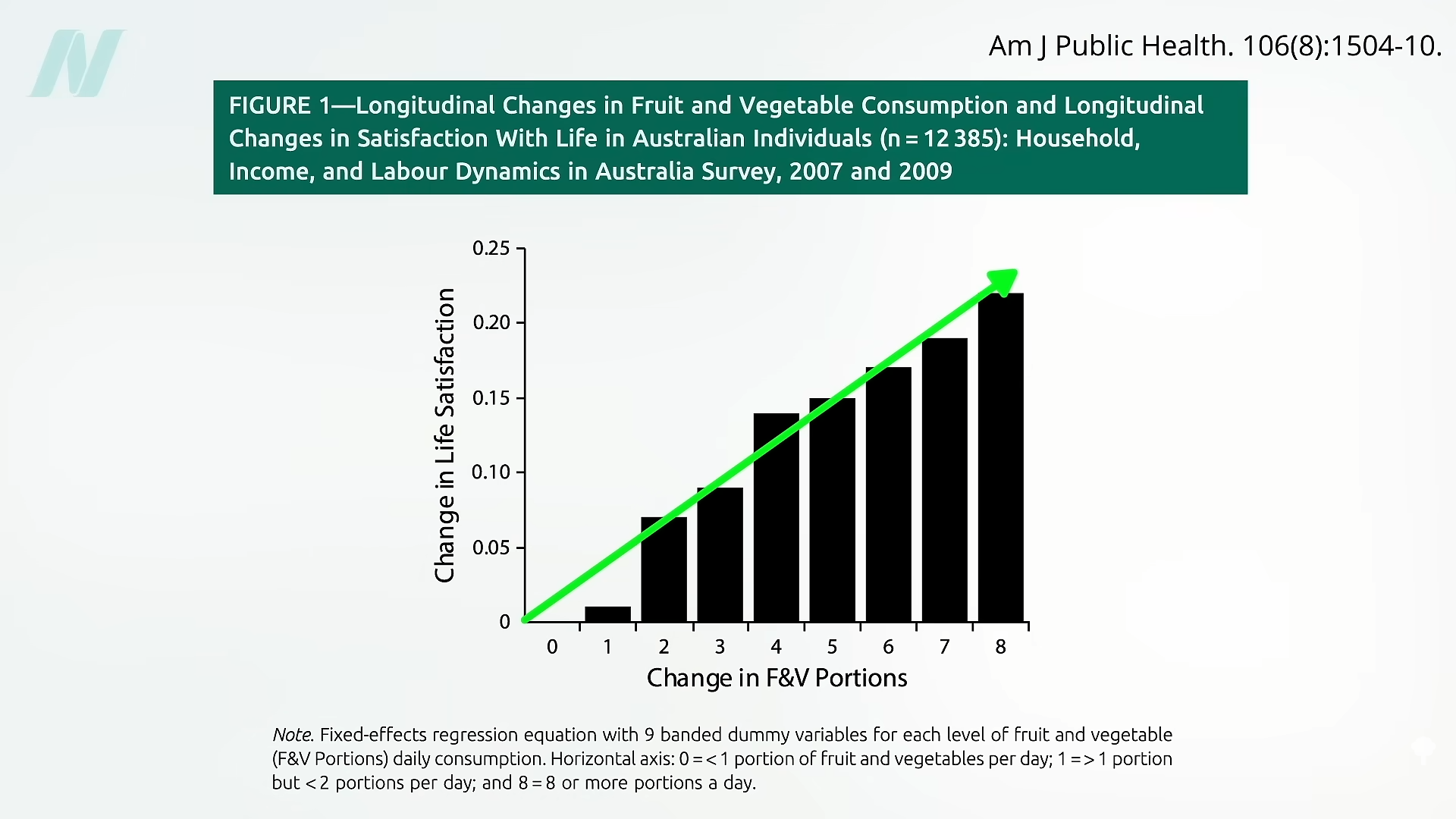

There is “a famous criticism in this area of research—namely, that deep-down personality or family upbringing might lead people simultaneously to eat in a healthy way and also to have better mental well-being, so that diet is then merely correlated with, but incorrectly gives the appearance of helping to cause, the level of well-being.” However, recent research circumvented this problem by examining if “changes in diet are correlated with changes in mental well-being”—in effect, studying the “Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness After Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables.” As you can see below and at 1:37 in my video Fruits and Vegetables Put to the Test for Boosting Mood, as individuals began eating more fruits and veggies, there was a straight-line increase in their change in life satisfaction over time.

“Increased fruit and vegetable consumption was predictive of increased happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being. They were up to 0.24 life-satisfaction points (for an increase of 8 portions a day), which is equal in size to the psychological gain of going from unemployment to employment.” (My Daily Dozen recommendation is for at least nine servings of fruits and veggies a day.)

That study was done in Australia. It was repeated in the United Kingdom, and researchers found the same results, though Brits may need to bump up their daily minimum consumption of fruits and vegetables to more like 10 or 11 servings a day.

As researchers asked in the title of their paper, “Does eating fruit and vegetables also reduce the longitudinal risk of depression and anxiety?” Improved well-being is nice, but “governments and medical authorities are often interested in the determinants of major mental ill-health conditions, such as depression and high levels of anxiety, and not solely in a more typical citizen’s level of well-being”—for instance, not just life satisfaction. And, indeed, using the same dataset but instead looking for mental illness, researchers found that “eating fruit and vegetables may help to protect against future risk of clinical depression and anxiety,” as well.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of dozens of studies found “an inverse linear association between fruit or vegetable intake and risk of depression, such that every 100-gram increased intake of fruit was associated with a 3% reduced risk of depression,” about half an apple. Yet, “less than 10% of most Western populations consume adequate levels of whole fruits and dietary fiber, with typical intake being about half of the recommended levels.” Maybe the problem is we’re just telling people about the long-term benefits of fruit intake for chronic disease prevention, rather than the near-immediate improvements in well-being. Maybe we should be advertising the “happiness’ gains.” Perhaps, but we first need to make sure they’re real.

We’ve been talking about associations. Yes, “a healthy diet may reduce the risk of future depression or anxiety, but being diagnosed with depression or anxiety today could also lead to lower fruit and vegetable intake in the future.” Now, in these studies, we can indeed show that the increase in fruit and vegetable consumption came first, and not the other way around, but as the great enlightenment philosopher David Hume pointed out, just because the rooster crows before the dawn doesn’t mean the rooster caused the sun to rise.

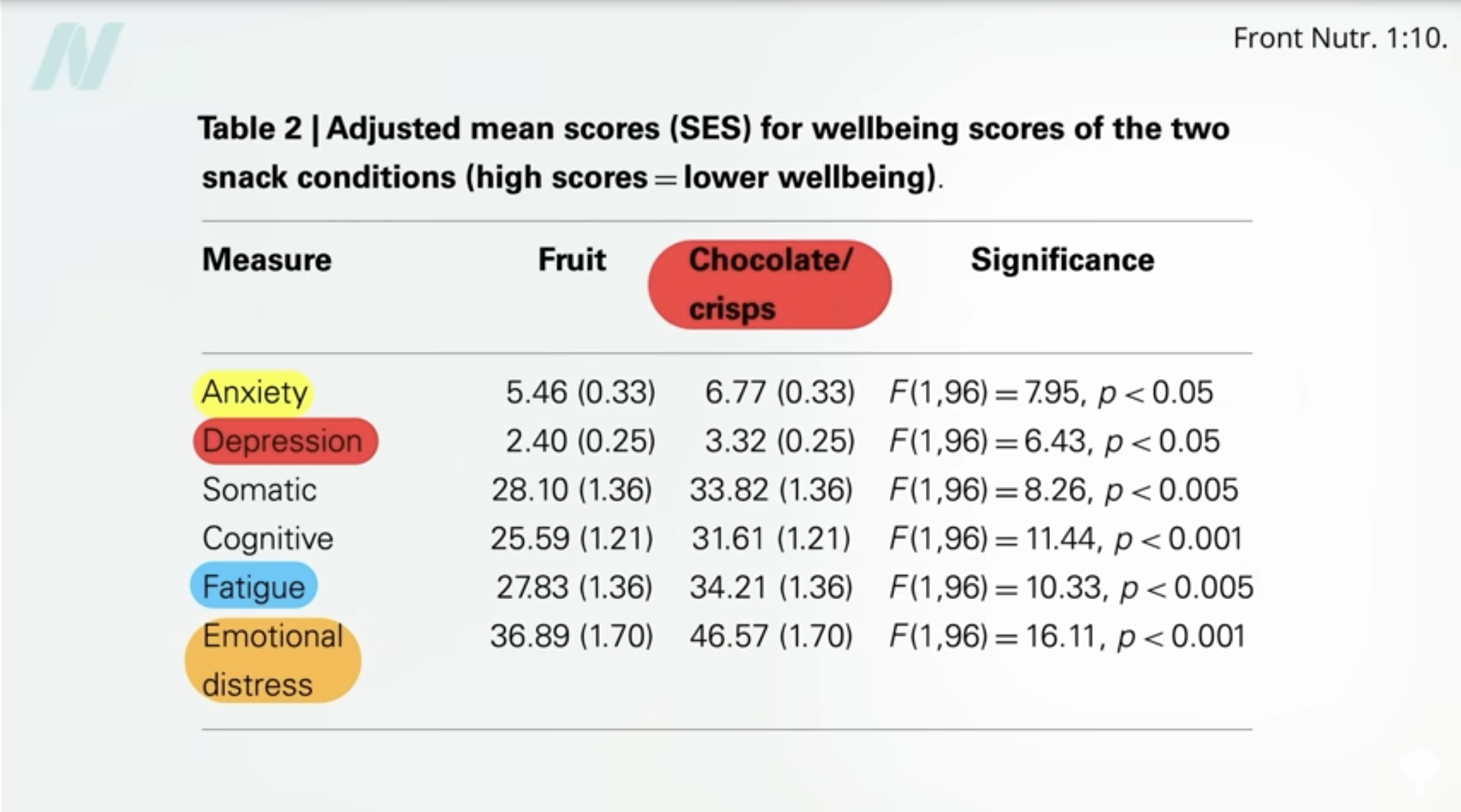

To prove cause and effect, we need to put it to the test with an interventional study. Unfortunately, to date, many studies have compared fruit to chocolate and chips, for instance. Indeed, study participants randomized to eat fruit showed significant improvements in anxiety, depression, fatigue, and emotional distress, which is amazing, but that was compared to chocolate and potato chips, as you can see below and at 4:26 in my video. Apples, clementines, and bananas making people feel better than assorted potato chips and chunky chocolate wafers is not exactly a revelation.

This is the kind of study I’ve been waiting for: a randomized controlled trial in which young adults were randomized to one of three groups—a diet-as-usual group, a group encouraged to eat more fruits and vegetables, or a third group given two servings of fruits and vegetables a day to eat in addition to their regular diet. Those in the third group “showed improvements to their psychological well-being with increases in vitality, flourishing, and motivation” within just two weeks. However, simply educating people to eat their fruits and vegetables may not be enough to reap the full rewards, so perhaps greater emphasis needs to be placed on providing people with fresh produce—for example, offering free fruit for people when they shop. I know that would certainly make me happy!