Identical twins don’t just share DNA; they also share a uterus. Might that help account for some of their metabolic similarities? “Fetal overnutrition, evidenced by large infant birth weight for gestational age, is a strong predictor of obesity in childhood and later life.” Could it be that you are what your mom ate?

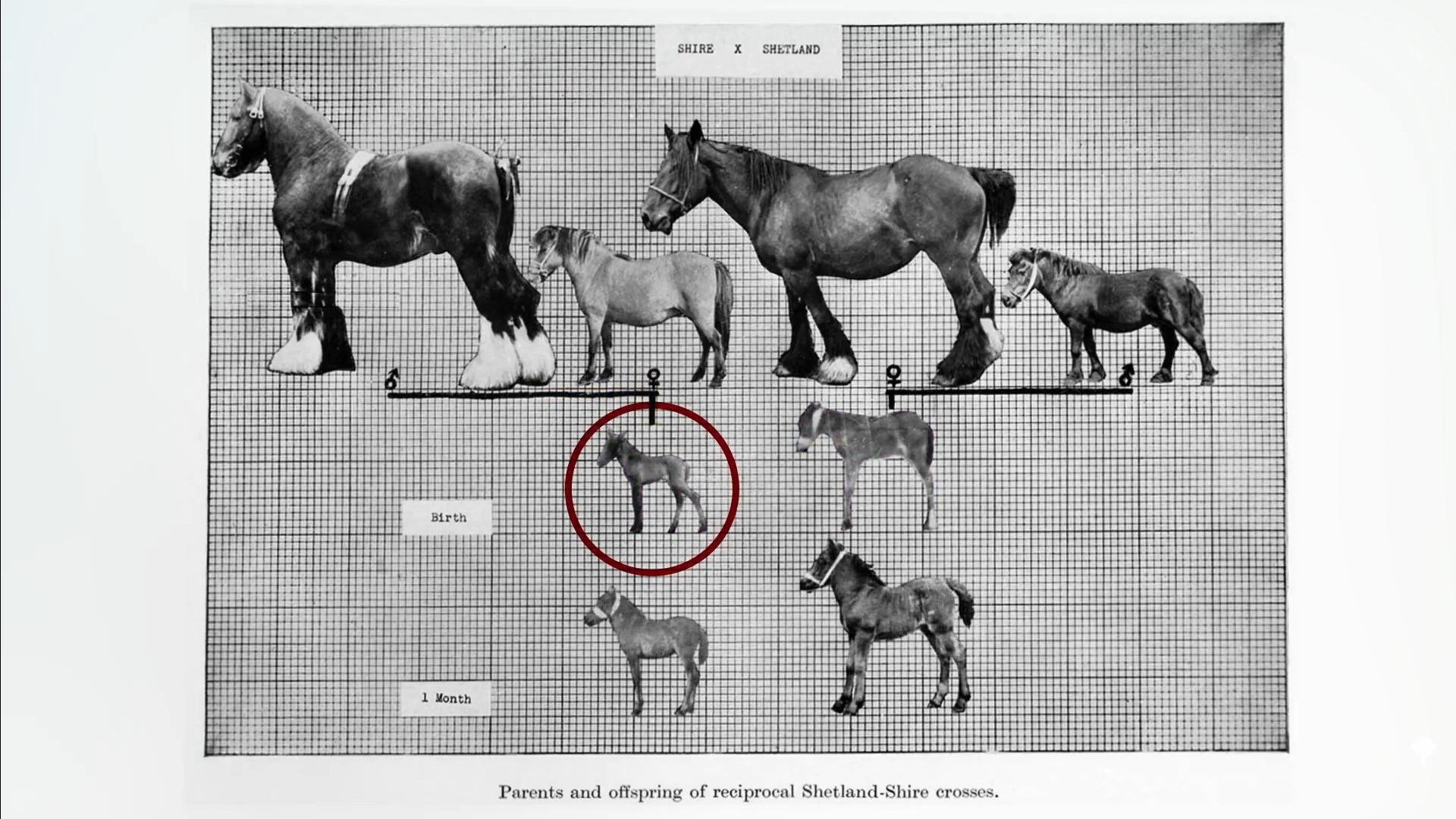

A dramatic illustration from the animal world is the crossbreeding of Shetland ponies with massive draft horses. Either way, the offspring are half pony/half horse, but when carried in the pony uterus, they come out much smaller, as you can see below and at 0:47 in my video The Role of Epigenetics in the Obesity Epidemic. (Thank heavens for the pony mother!) This is presumably the same reason why the mule (horse mom and donkey dad) is larger than the hinny (donkey mom and horse dad). The way you test this in people is to study the size of babies from surrogates after in vitro fertilization.

Who do you think most determines the birth weight of a test-tube baby? Is it the donor mom who provided all the DNA or the surrogate who provided the intrauterine environment? When it was put to the test, the womb won. Incredibly, a baby who had a thin biological mother but was born to a surrogate with obesity may harbor a greater risk of becoming obese than a baby with a heavier biological mother but born to a slim surrogate. The researchers “concluded that the environment provided by the human mother is more important than her genetic contribution to birth weight.”

The most compelling data come from comparing obesity rates in siblings born to the same mother, before and after her bariatric surgery. Compared to their brothers and sisters born before the surgery, those born when mom weighed about 100 pounds less had lower rates of inflammation, metabolic derangements, and, most critically, three times less risk of developing severe obesity—35 percent of those born before the weight loss were affected, compared to 11 percent born after. The researchers concluded that “these data emphasize how critical it is to prevent obesity and treat it effectively to prevent further transmission to future generations.”

Hold on. Mom had the same DNA before and after surgery. She passed down the same genes. How could her weight during pregnancy affect the weight destiny of her children any differently? Darwin himself admitted, “In my opinion, the greatest error which I have committed, has been not allowing sufficient weight to the direct action of the environment, i.e. food…independently of natural selection.” We finally figured out the mechanism by which this can happen—epigenetics.

Epigenetics, which means “above genetics,” layers an extra level of information on top of the DNA sequence that can be affected by our surroundings, as well as potentially passed on to our children. This is thought to explain the “developmental programming” that can occur in the womb, depending on the weight of the mother—or even the grandmother. Since all the eggs in your infant daughter’s ovaries are already preformed before birth, a mother’s weight status during pregnancy could potentially affect the obesity risk of her grandchildren, too. Either way, you can imagine how this could result in an intergenerational vicious cycle where obesity begets obesity.

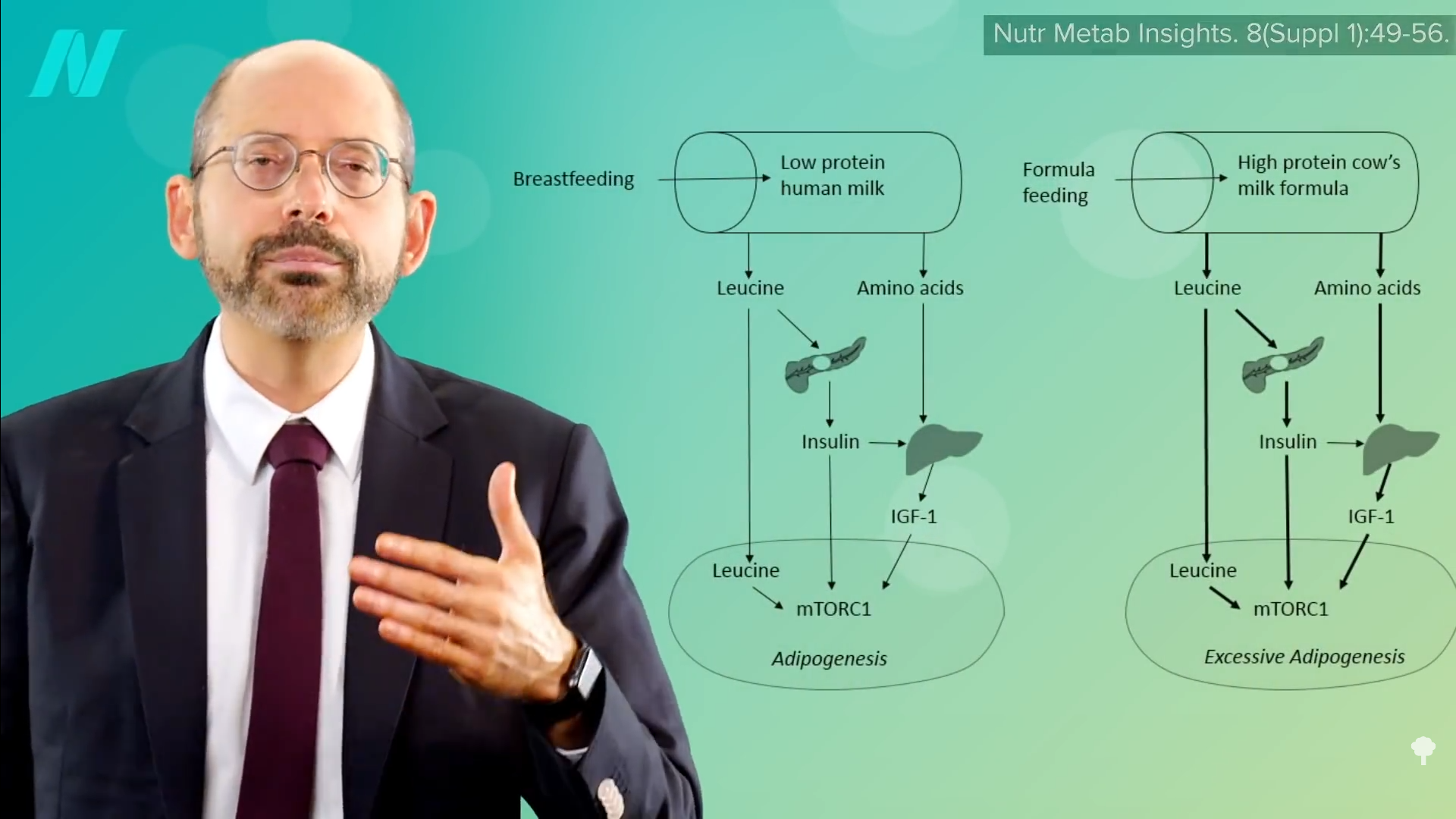

Is there anything we can do about it? Well, breastfed infants may be at lower risk for later obesity, though the benefits may be confined to those who are exclusively breastfed, as the effect may be due to growth factors triggered by exposure to the excess protein in baby formula, as you can see below and at 3:51 in my video. The breastfeeding data are controversial, though, with charges leveled of a “white hat bias.” That’s the concern that public health researchers might disproportionally shelve research results that don’t fit some goal for the greater good. (In this case, preferably publishing breastfeeding studies showing more positive results.) But, of course, that criticism came from someone who works for an infant formula company. Breast is best, regardless. However, its role in the childhood obesity epidemic remains arguably uncertain.

Prevention may be the key. Given the epigenetic influence of maternal weight during pregnancy, a symposium of experts on pediatric nutrition concluded that “planning of pregnancy, including prior optimization of maternal weight and metabolic condition, offers a safe means to initiate the prevention rather than treatment of pediatric obesity.” Easier said than done, but overweight moms-to-be may take comfort in the fact that after the weight loss in the surgery study, even the moms who gave birth to kids with three times lower risk were still, on average, obese themselves, suggesting weight loss before pregnancy is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

What triggered the whole obesity epidemic to begin with? There are a multitude of factors, and I covered many of them in my 11-video series on the epidemic in the related posts below.

We are what our moms ate in other ways, too. Check out: