I debunk the myth of protein as the most satiating macronutrient.

The importance of satiety is underscored by a rare genetic condition known as Prader-Willi syndrome. Children with the disorder are born with impaired signaling between their digestive system and their brain, so they don’t know when they’re full. “Because no sensation of satiety tells them to stop eating or alerts their body to throw up, they can accidentally consume enough in a single binge to fatally rupture their stomach.” Without satiety, food can be “a death sentence.”

Protein is often described as the most satiating macronutrient. People tend to report feeling fuller after eating a protein-rich meal, compared to a carbohydrate- or fat-rich one. The question is: Does that feeling of fullness last? From a weight-loss standpoint, satiety ratings only matter if they end up cutting down on subsequent calorie intake, and even a review funded by the meat, dairy, and egg industries acknowledges that this does not seem to be the case for protein. Hours later, protein consumed earlier doesn’t tend to end up cutting calories later on.

Fiber-rich foods, on the other hand, can suppress appetite and reduce subsequent meal intake more than ten hours after consumption—even the next day—because their site of action is 20 feet down in the lower intestine. Remember the ileal brake from my Evidence-Based Weight Loss lecture? When researchers secretly infused nutrients into the end of the small intestine, study participants spontaneously ate as many as hundreds fewer calories at a meal. Our brain gets the signal that we are full, from head to tail.

We were built for gluttony. “It is a wonderful instinct, developed over millions of years, for times of scarcity.” Stumbling across a rare bounty, those who could fill themselves the most to build up the greatest reserves would be more likely to pass along their genes. So, we are hard-wired not just to eat until our stomach is full, but until our entire digestive tract is occupied. Only when our brain senses food all the way down at the end does our appetite fully dial down.

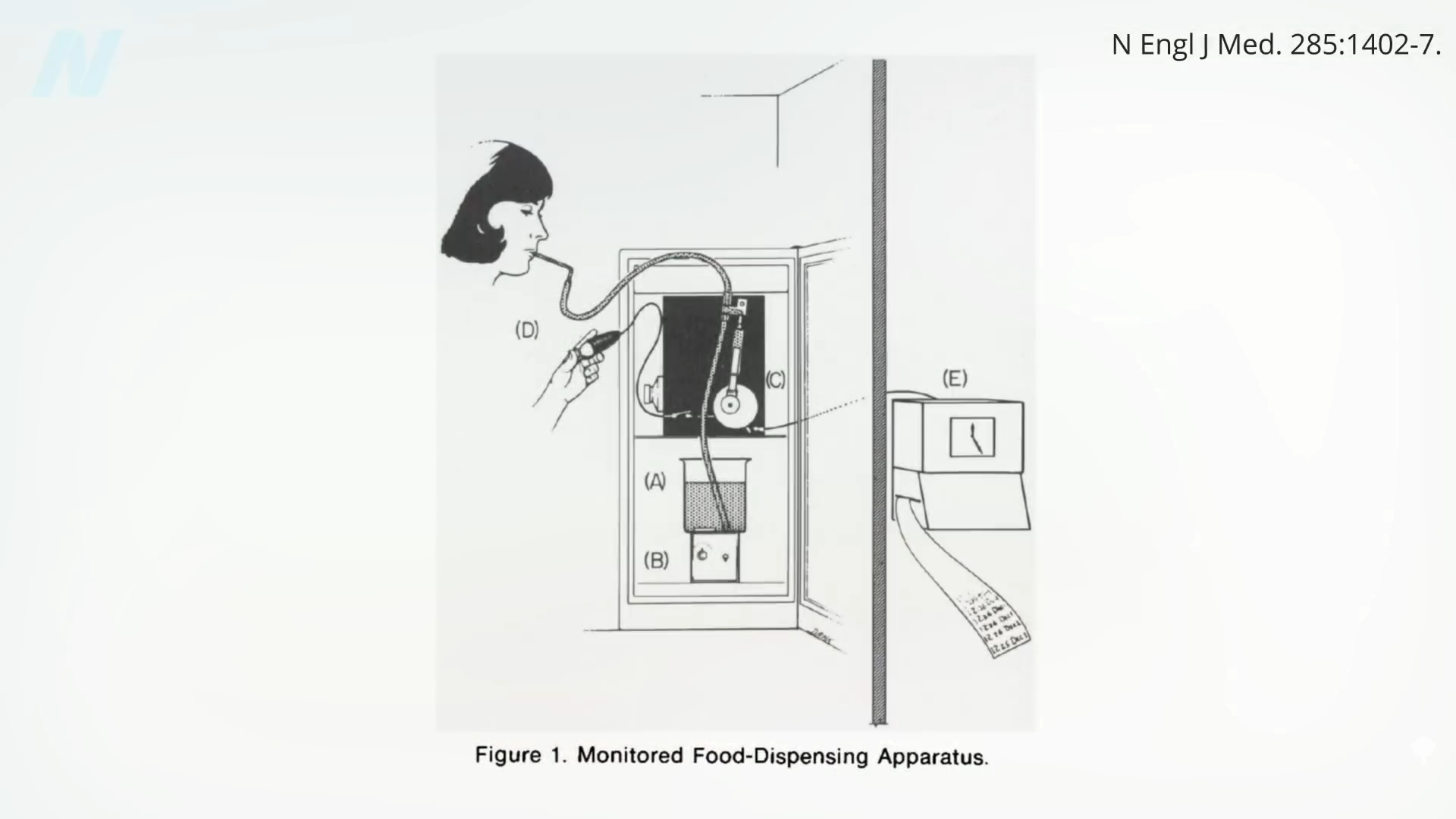

Fiber-depleted foods get rapidly absorbed early on, though, so much of it never makes it down to the lower gut. As such, if our diet is low in fiber, no wonder we’re constantly hungry and overeating; our brain keeps waiting for the food that never arrives. That’s why people who even undergo stomach-stapling surgeries that leave them with a tiny two-tablespoon-sized stomach pouch can still eat enough to regain most of the weight they initially lost. Without sufficient fiber, transporting nutrients down our digestive tract, we may never be fully satiated. But, as I described in my last video, one of the most successful experimental weight-loss interventions ever reported in the medical literature involved no fiber at all, as you can see here and at 2:47 in my video Foods Designed to Hijack Our Appetites.

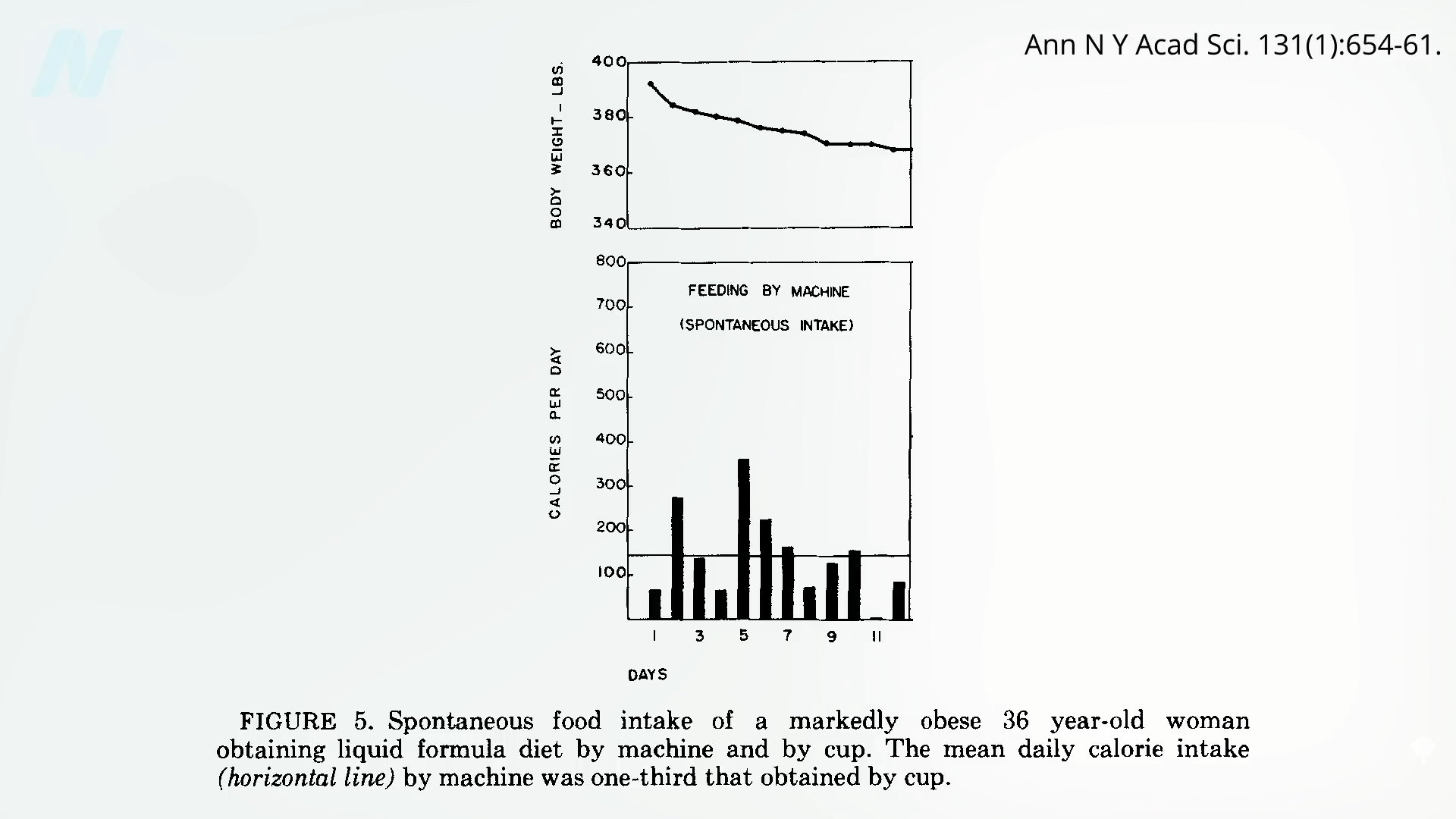

At first glance, it might seem obvious that removing the pleasurable aspects of eating would cause people to eat less, but remember, that’s not what happened. The lean participants continued to eat the same amount, taking in thousands of calories a day of the bland goop. Only those who were obese went from eating thousands of calories a day down to hundreds, as shown below and at 3:22 in my video. And, again, this happened inadvertently without them apparently even feeling a difference. Only after eating was disconnected from the reward was the body able to start rapidly reining in the weight.

At first glance, it might seem obvious that removing the pleasurable aspects of eating would cause people to eat less, but remember, that’s not what happened. The lean participants continued to eat the same amount, taking in thousands of calories a day of the bland goop. Only those who were obese went from eating thousands of calories a day down to hundreds, as shown below and at 3:22 in my video. And, again, this happened inadvertently without them apparently even feeling a difference. Only after eating was disconnected from the reward was the body able to start rapidly reining in the weight.

We appear to have two separate appetite control systems: “the homeostatic and hedonic pathways.” The homeostatic pathway maintains our calorie balance by making us hungry when energy reserves are low and abolishes our appetite when energy reserves are high. “In contrast, hedonic or reward-based regulation can override the homeostatic pathway” in the face of highly palatable foods. This makes total sense from an evolutionary standpoint. In the rare situations in our ancestral history when we’d stumble across some calorie-dense food, like a cache of unguarded honey, it would make sense for our hedonic drive to jump into the driver’s seat to consume the scarce commodity. Even if we didn’t need the extra calories at the time, our body wouldn’t want us to pass up that rare opportunity. Such opportunities aren’t so rare anymore, though. With sugary, fatty foods around every corner, our hedonic drive may end up in perpetual control, overwhelming the intuitive wisdom of our bodies.

We appear to have two separate appetite control systems: “the homeostatic and hedonic pathways.” The homeostatic pathway maintains our calorie balance by making us hungry when energy reserves are low and abolishes our appetite when energy reserves are high. “In contrast, hedonic or reward-based regulation can override the homeostatic pathway” in the face of highly palatable foods. This makes total sense from an evolutionary standpoint. In the rare situations in our ancestral history when we’d stumble across some calorie-dense food, like a cache of unguarded honey, it would make sense for our hedonic drive to jump into the driver’s seat to consume the scarce commodity. Even if we didn’t need the extra calories at the time, our body wouldn’t want us to pass up that rare opportunity. Such opportunities aren’t so rare anymore, though. With sugary, fatty foods around every corner, our hedonic drive may end up in perpetual control, overwhelming the intuitive wisdom of our bodies.

So, what’s the answer? Never eat really tasty food? No, but it may help to recognize the effects hyperpalatable foods can have on hijacking our appetites and undermining our body’s better judgment.

Ironically, some researchers have suggested a counterbalancing evolutionary strategy for combating the lure of artificially concentrated calories. Just as pleasure can overrule our appetite regulation, so can pain. “Conditioned food aversions” are when we avoid foods that made us sick in the past. That may just seem like common sense, but it is actually a deep-seated evolutionary drive that can defy rationality. Even if we know for a fact a particular food was not the cause of an episode of nausea and vomiting, our body can inextricably tie the two together. This happens, for example, with cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Consoling themselves with a favorite treat before treatment can lead to an aversion to their favorite food if their body tries to connect the dots. That’s why oncologists may advise the “scapegoat strategy” of only eating foods before treatment that you are okay with, never wanting to eat again.

Researchers have experimented with inducing food aversions by having people taste something before spinning them in a rotating chair to cause motion sickness. Eureka! A group of psychologists suggested: “A possible strategy for encouraging people to eat less unhealthy food is to make them sick of the food, by making them sick from the food.” What about using disgust to promote eating more healthfully? Children as young as two-and-a-half years old will throw out a piece of previously preferred candy scooped out of the bottom of a clean toilet.

Thankfully, there’s a way to exploit our instinctual drives without resorting to revulsion, aversion, or bland food, which we’ll explore next.