Do the benefits outweigh the risks of acid-blocker drugs, also known as proton pump inhibitors like Nexium, Prilosec, and Zantac? What about baking soda?

Dyspepsia is the medical term for upset stomach. After eating, your stomach may hurt, you may feel bloated, nauseous, or overly full, or you may belch. “Despite the high prevalence of the disorder, there are no approved treatments” for dyspepsia in the Western world. As I discuss in my video Are Acid-Blocking Drugs Safe?, this leads people to seek out alternatives like baking soda, which a manufacturer promotes for use in upset stomach. The problem is that it contains sodium bicarbonate, so it “has the potential for significant toxicity when ingested in excessive amounts.” And, “issue of baking soda can result in serious electrolyte and acid/base imbalances.”

Baking soda labels were modified in 1990 to include the warning “Do not administer to children under age 5,” “because of reported seizure and respiratory depression in children.” Even “a pinch” may be too much for an infant, and a few large spoonsful could be fatal for a child.

Another new addition to the product’s label is the “stomach warning,” stressing the importance of not taking baking soda when overly full with food or drink. Why not? If you’re familiar with baking soda and vinegar volcanoes, popular at most every scholastic science fair, you understand the risk! It’s just like adding baking soda to the acid in your stomach. “This warning was added at the request of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) because of multiple case reports of spontaneous gastric rupture”—that is, when stomachs actually burst.

Exploding stomachs aside, just sticking to the suggested dose may still cause adverse effects. So, baking soda cannot be recommended for dyspepsia, especially for young children, pregnant women, alcoholics, and people on diuretics, which are common blood pressure medications sometimes referred to as water pills.

What about acid-blocking drugs like Nexium or Prilosec? They work better than sugar pills, but not by much, helping 31 percent of dyspepsia sufferers compared to 26 percent helped by placebo. In other words, the drugs are 5 percent better than nothing! These so-called proton pump inhibitors “have also been extremely lucrative for the pharmaceutical industry,” raking in billions of dollars annually. But, we now have massive computerized databases of patients, so we can start to evaluate their possible long-term adverse effects, including increased pneumonia, bone fractures, intestinal infections, heart disease, kidney failure, and even all-cause mortality. “The latest concern to surface has been the association between PPI [proton pump inhibitor] use and risk of dementia”!

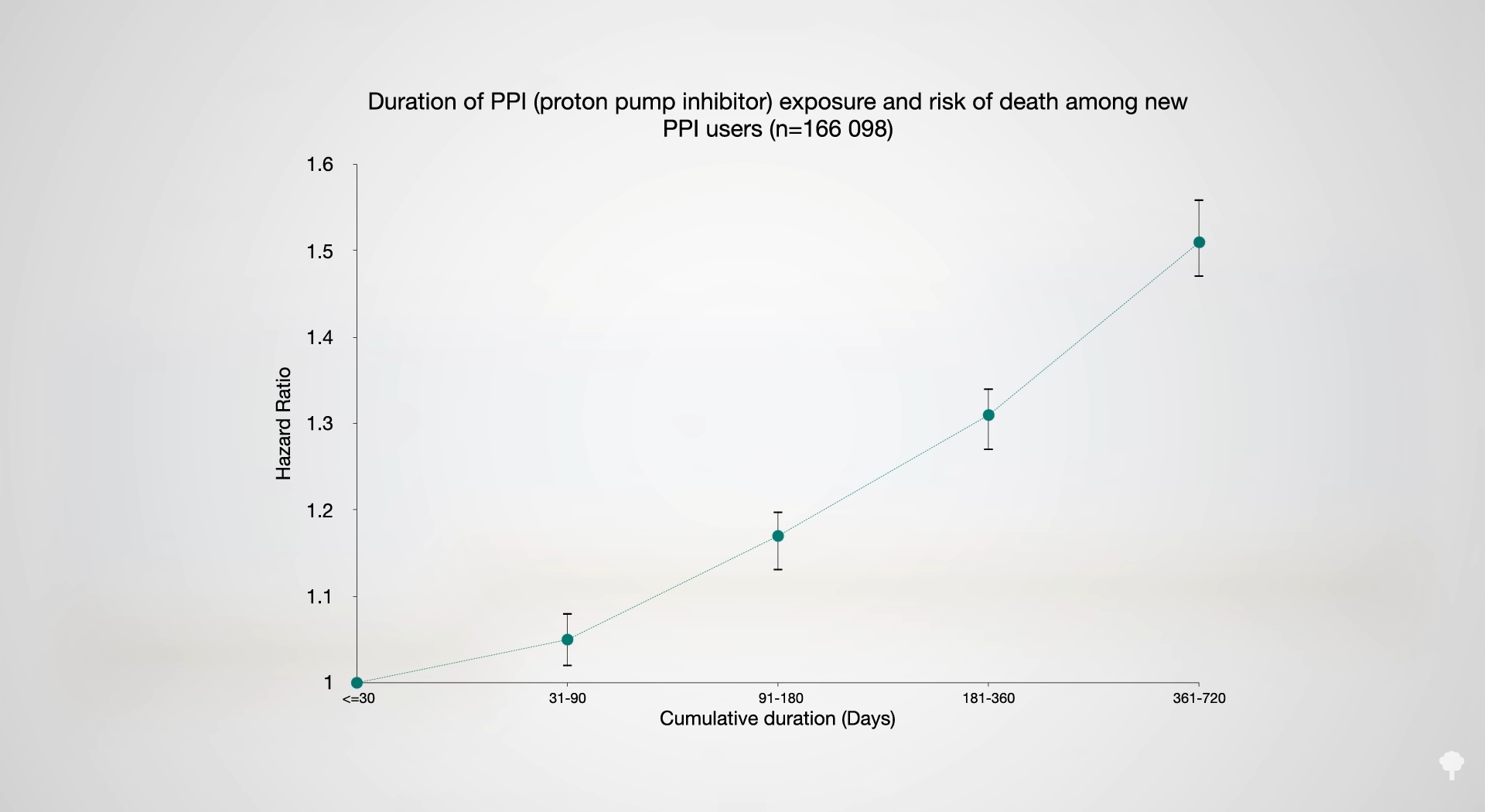

The problem with all of these studies just showing “associations” is they don’t prove cause-and-effect. Maybe taking the drugs didn’t make people sick. Maybe being sick made people take the drugs. Or, maybe these drugs are not the cause of these infections, fractures, death, and dementia. Maybe they are markers for being sicker. There are potential mechanisms by which these drugs could have some of these effects. As you can see at 3:00 in my video, the longer people are exposed to the drugs, the higher their apparent risk of dying prematurely. How could suppressing acid production in the stomach increase mortality from a cause like heart disease? Well, suppressing acid isn’t the only thing these drugs do. They may also a reduction in nitric-oxide synthase, the enzyme that makes the “open sesame” molecule that helps keep our arteries healthy.

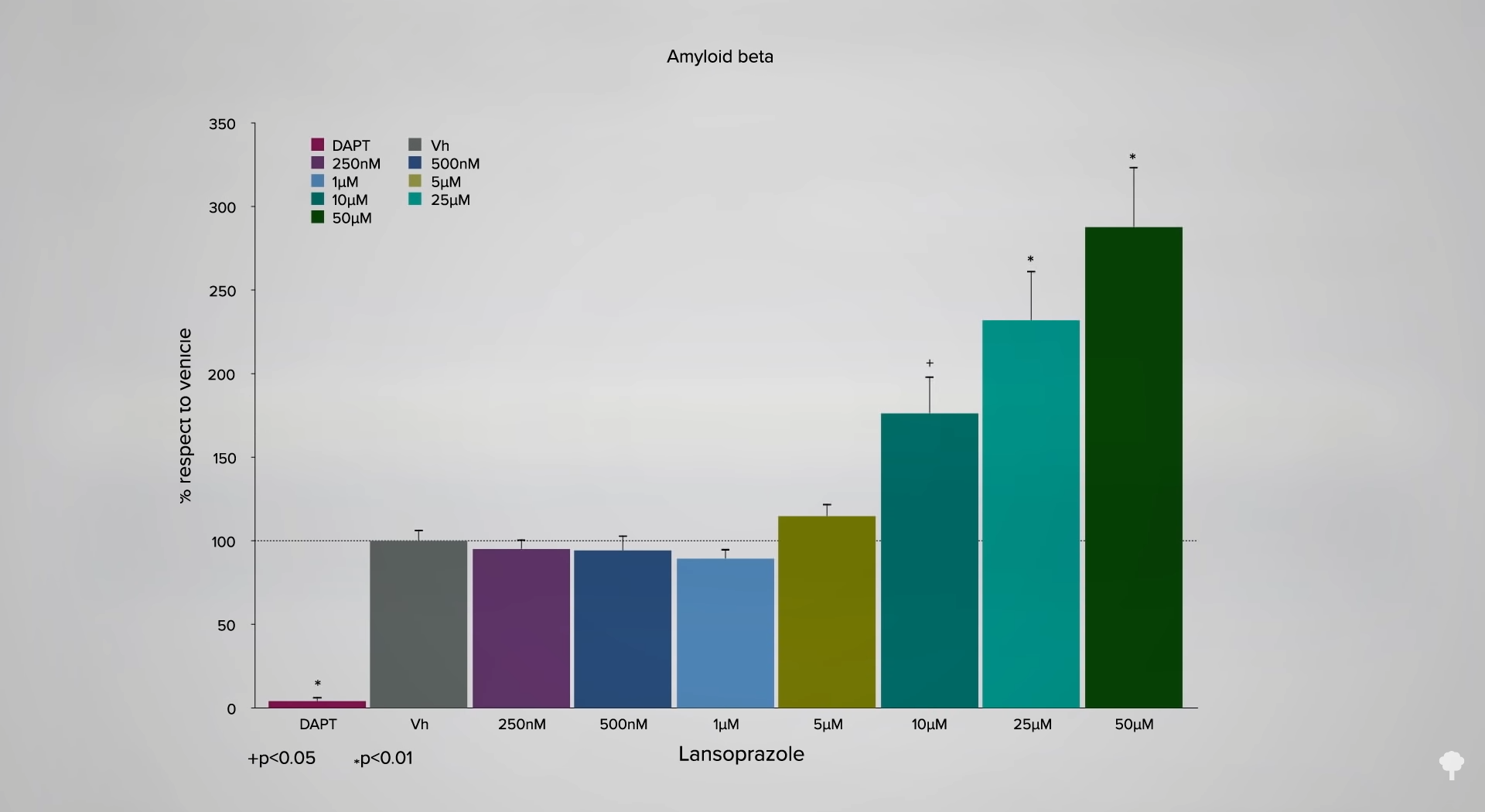

In terms of dementia, a key event in the development of Alzheimer’s disease is the accumulation of sticky protein plaques called amyloid-beta. If you put Alzheimer’s-like cells in a petri dish and drip on increasing levels of the drug Prevacid, the diseased cells start churning out more amyloid. The same occurs with Prilosec, Losec, Protonix, and Nexium, as you can see at 3:39 in my video.

Just because something happens in a petri dish or a mouse model doesn’t mean it happens in humans, though. That is certainly true, but most studies to date have found this link between “an increased risk of dementia with the use of PPIs,” these proton pump inhibitor drugs. The largest such study to date, involving tens of thousands of patients, concluded that avoiding the chronic use of these drugs “may prevent the development of dementia.” An alternative explanation of the link is aluminum exposure, which itself may play a role in dementia. Maybe people using acid-blocking drugs have heartburn and use more aluminum-containing antacids, which are the actual culprit? We still don’t know.

We do know, however, there is “an almost cultish faith” in stomach-acid suppression as some kind of medical panacea, which “has led to a progressive escalation of PPI dosage and potency,” while mounting evidence suggests the drugs “are associated with a number of adverse effects and are overprescribed.” How overprescribed? The “rate of inappropriate use of these drugs is on average above 57% in patients admitted to general medical wards and 50% in patients managed in the primary care setting,” so about half. Half of the people on these drugs shouldn’t even be on them! “These rates are very high and worrying, because they mean that PPIs are prescribed for indications other than those recommended by expert consensus statements”—that is, for conditions they shouldn’t even be prescribed for, meaning there are no proven benefits to outweigh the risks.

I explore dyspepsia further in my video Flashback Friday: The Best Diet for Upset Stomach.