How does sorghum compare with other grains in terms of protein, antioxidants, and micronutrients? And the benefits of red sorghum compared to black and white varieties?

Sorghum is “the Forgotten Grain.” The United States is the top producer of sorghum, “but it is typically not used to produce food for American consumers.” Instead, it’s used mainly “to produce livestock feed, pet foods, household building materials…but it is a preferred grain for human diets in other parts of the world, such as Africa and Asia.” There, it’s been a staple and eaten for thousands of years, making it currently the fifth most popular grain grown after wheat, corn, rice, and barley, beating out oats and rye.

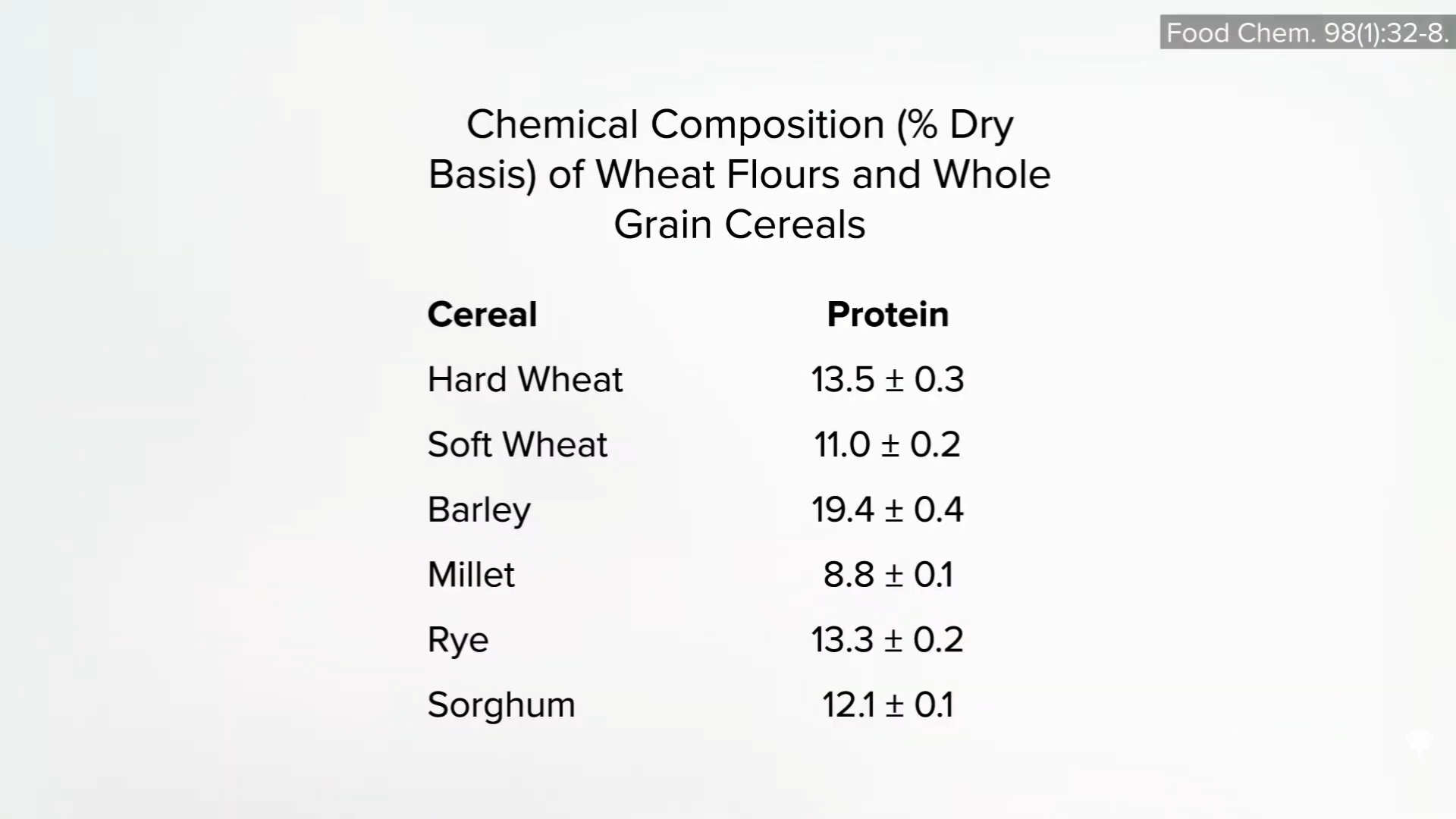

Because sorghum is gluten-free and “can be definitively considered safe for consumption by people with celiac disease,” we’re starting to see it “increasingly used” as actual human food in the United States, so I decided to look into just how healthy it might be. As you can see below and at 0:59 in my video Is Sorghum a Healthy Grain?, it is comparable to other grains when it comes to protein.

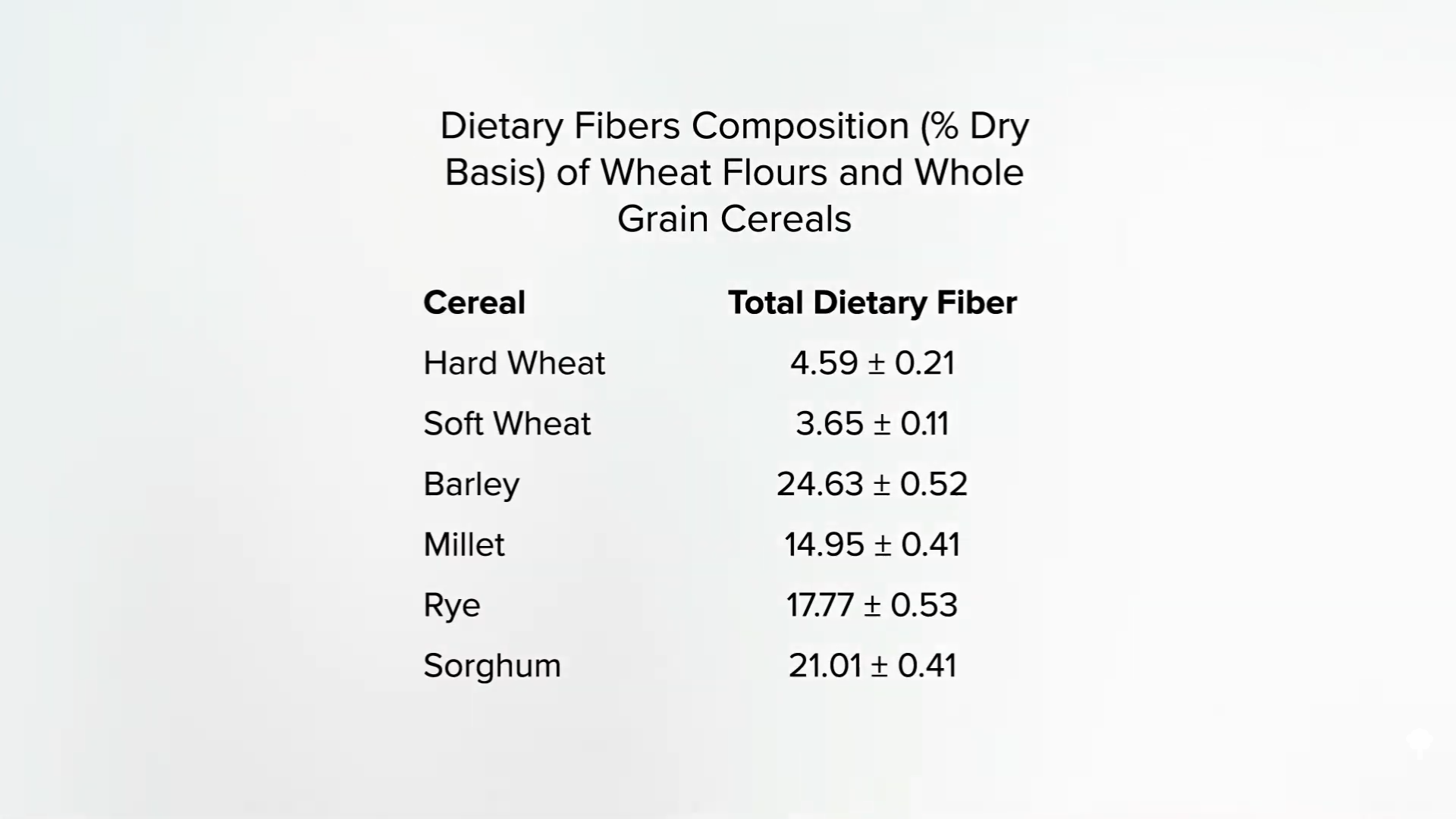

Since when do we have to worry about getting enough protein, though? Fiber is what Americans are desperately deficient in, and sorghum does pull towards the front of the pack, as seen here and at 1:06 in my video.

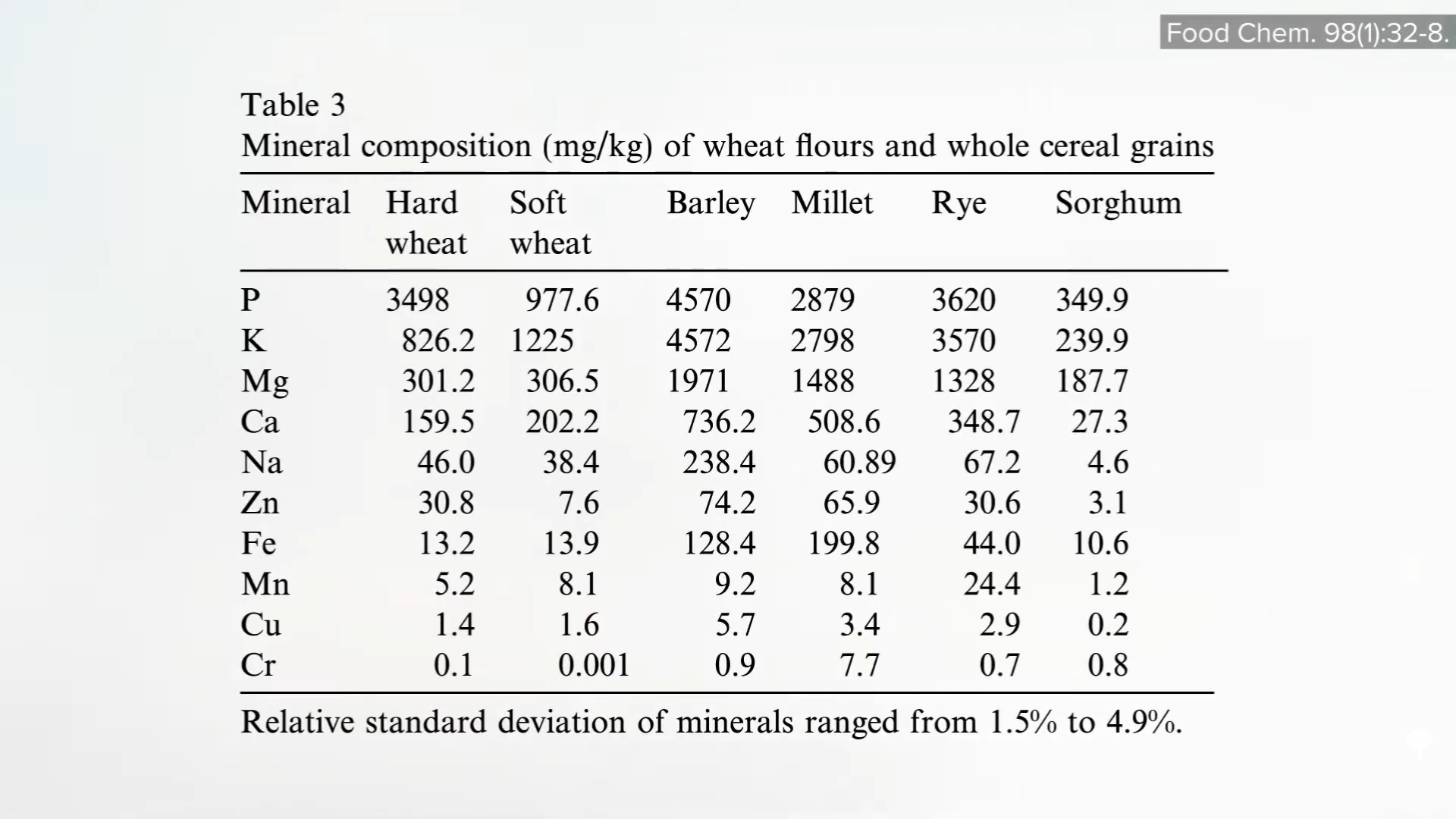

The micronutrient composition is relatively “unremarkable, relative to other cereal grains.” As shown below and at 1:15 in my video, you can see how it rates on minerals, for example.

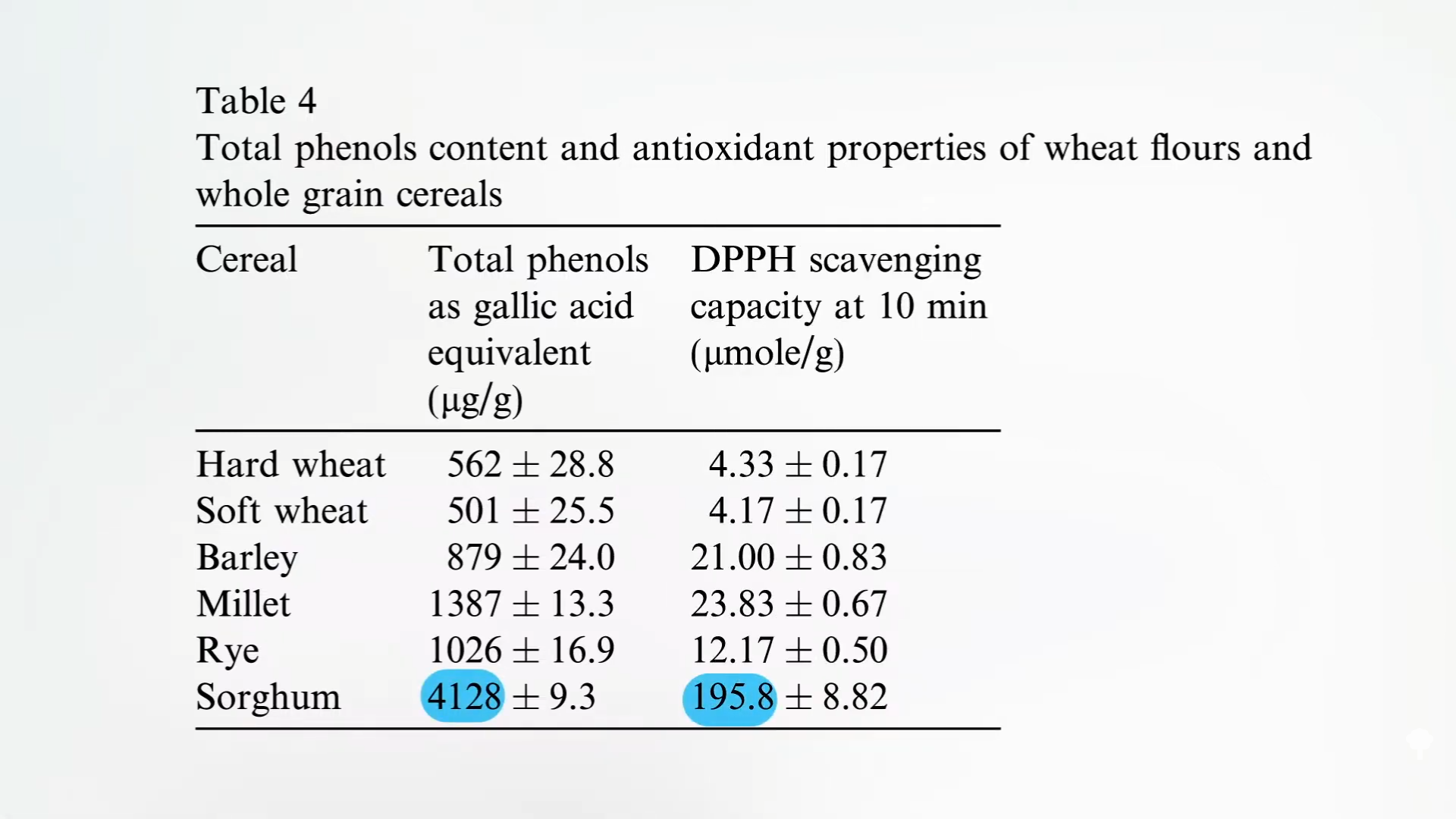

Where sorghum shines is its polyphenol content. Polyphenols are plant compounds and “their regular consumption has been associated with a reduced risk of a number of chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and neurodegenerative disorders.” It’s also been shown to have “a protective effect…on all-cause mortality.” If you compare different grains, sorghum really does pull ahead, helping to explain why its antioxidant power is so much higher, as seen here and at 1:40 in my video.

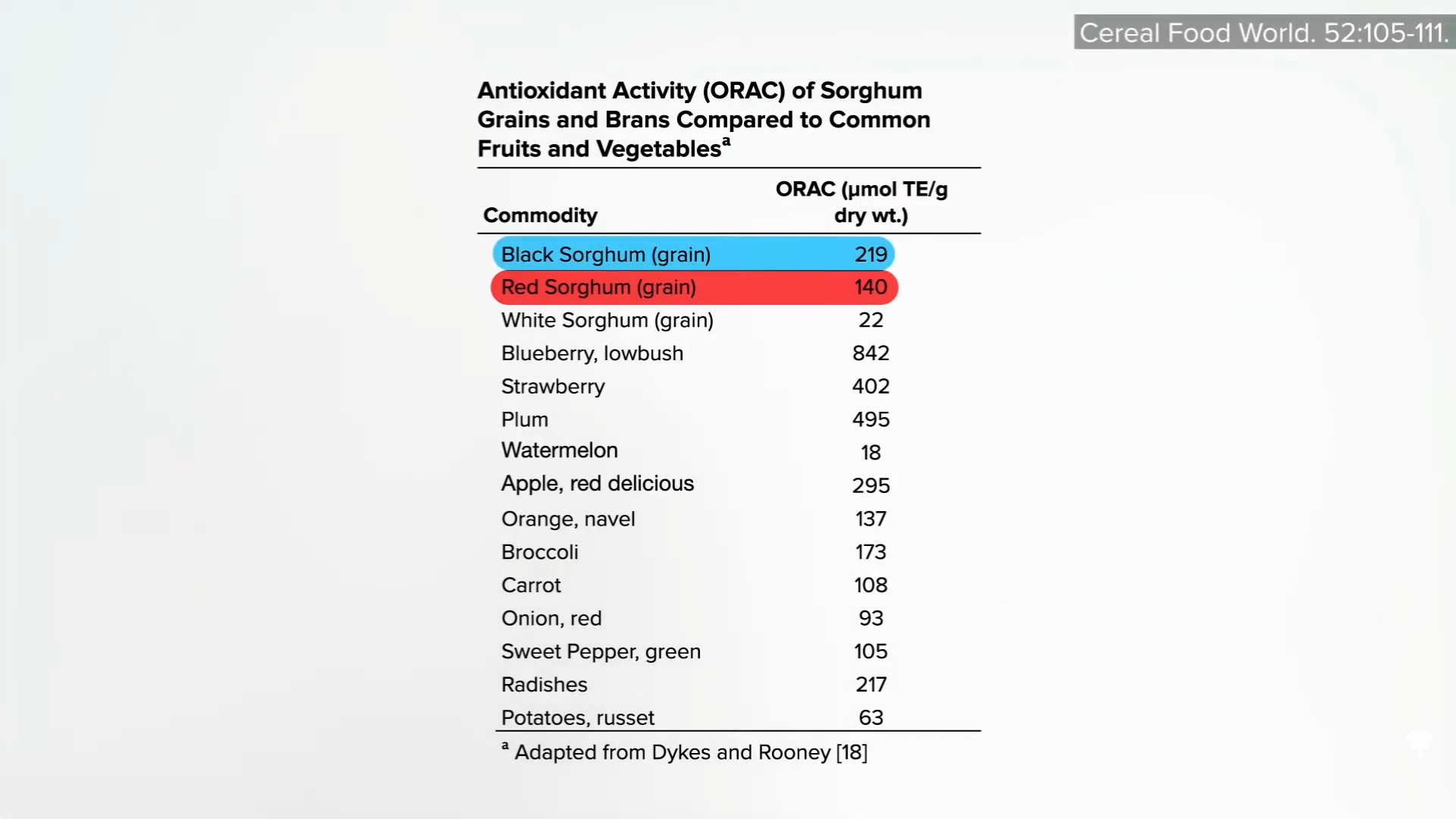

Now, sorghum gets its grainy butt kicked by fruits and vegetables, but when compared to other grains, a sorghum-based breakfast cereal, for example, might have about eight times the antioxidants than a whole wheat-based one. What we care about, though, isn’t antioxidant activity in a test tube, but antioxidant activity within our body.

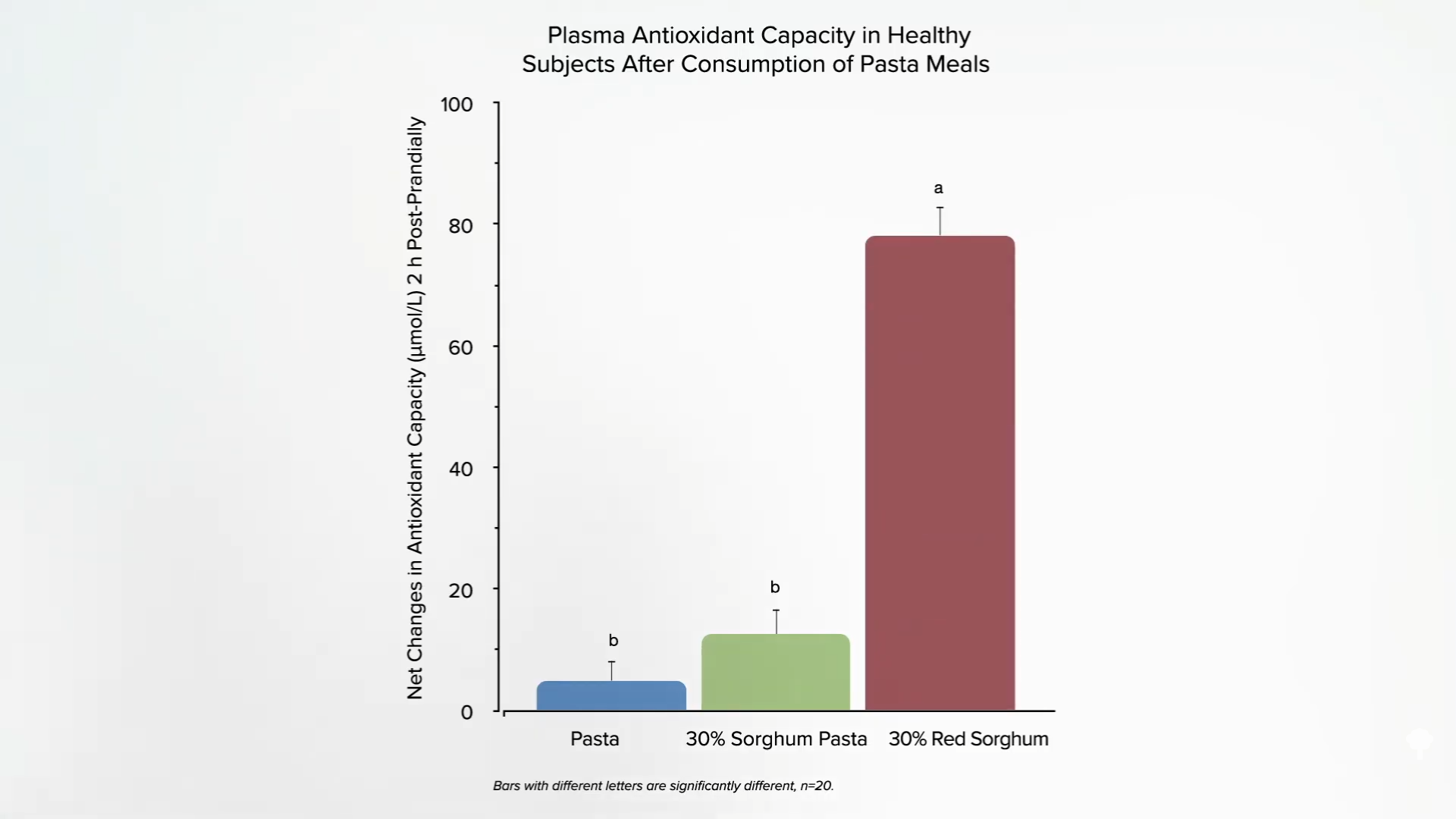

If you measure the antioxidant capacity of your blood after eating regular pasta, it goes up a little. If you replace 30 percent of the wheat flour with sorghum flour, it doesn’t go up much higher. But, if you eat 30 percent red sorghum flour pasta, the antioxidant capacity in your bloodstream shoots up about 15-fold, as seen below and at 2:22 in my video.

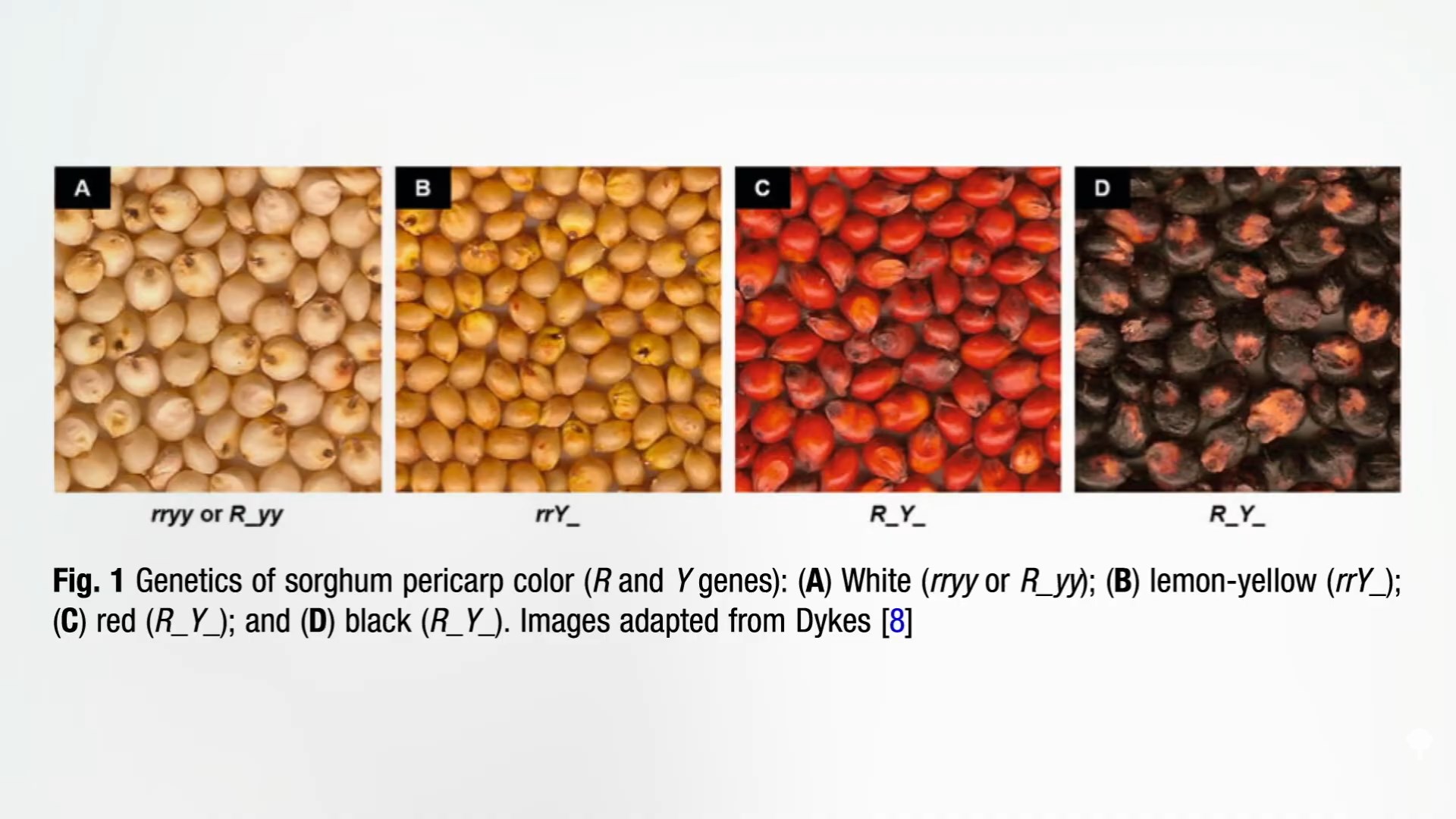

Red sorghum? Yes. In fact, there are multiple types of sorghum—such as black sorghum, white sorghum, and red sorghum. Below and at 2:31 in my video is how they look in grain form (including yellow sorghum).

Red sorghum and especially black sorghum have extremely high antioxidant activity, comparable to fruits and vegetables, as seen here and at 2:41.

The problem is I can’t find any of the colored sorghum varieties. I can go online and buy red or black rice, purple, blue, or red popping corn, and purple or black barley, but red or black sorghum can be harder to find. White sorghum is widely available for about four dollars a pound, though. Does it have any “unique nutritional and health-promoting attributes”? It’s promoted as “An Underutilized Cereal Whole Grain with the Potential to Assist in the Prevention of Chronic Disease,” according to a study title, but what is the “effect of sorghum consumption on health outcomes”?

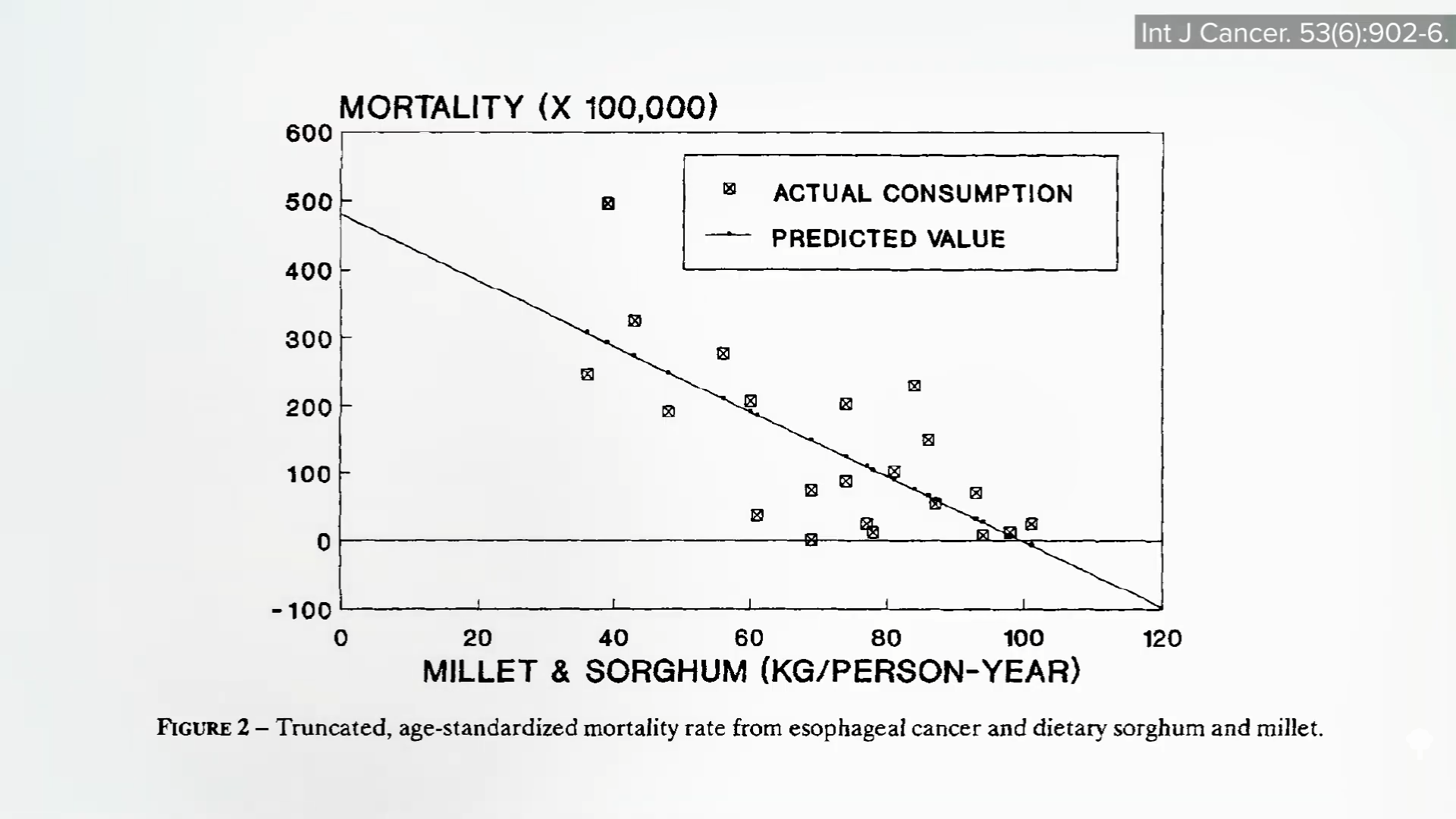

As you can see below and at 3:20 in my video, an epidemiological study in China found lower esophageal cancer mortality rates in areas where more millet and sorghum were eaten, compared to corn and wheat, but that may have been due more to avoiding fungal contamination of corn than from any benefit of sorghum itself. Though, it’s possible. “Oats are the only source of avenanthramides,” which give oats some unique health benefits. Similarly, sorghum, even white sorghum, contains unique pigments known as 3-deoxyanthocyanins, which are strong inducers of some of the detoxifying enzymes in our liver and can inhibit the growth of human cancer cells growing in a petri dish, compared to red cabbage, for instance, which just has regular anthocyanin pigments. White sorghum didn’t do much worse than red or black varieties, which have way more of the unique 3-deoxyanthocyanins, so it may just be a general sorghum effect. You don’t know until you put it to the test.

Researchers found that sorghum suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in human breast cancer xenografts. What does that mean? They concluded that sorghum could be used as “an inexpensive natural cancer therapy, without any side effects. We strongly recommend the use of [sorghum] as an edible therapeutic agent as it possesses tumor suppression, migration inhibition, and anti-metastatic effects on breast cancer” for humans. However, xenograft means human breast cancer implanted in a mouse. Yes, the human tumors grew more slowly in the mice-fed sorghum extracts and blocked metastasis to the lung. Yes, sorghum did the same for human colon cancer that, again, was in mice, but that can’t necessarily be translated to how human cancers would grow in humans, since not only do these mice not have a human immune system, they hardly have any immune system at all. They’re bred without a thymus gland, which is where cancer-fighting immunity largely originates. I mean, how else could you keep the mouse’s immune system from rejecting the human tissue outright? But this immunosuppression makes these kinds of mouse models that much more artificial—and that much more difficult to extrapolate to humans.

And that’s a lot of what we see in the sorghum literature—in vitro data from test tubes and petri dishes, and data from rats and mice. There has been “a critical missing piece of the puzzle” needed to link laboratory data to actual benefits in humans. Missing, that is, until now. Thankfully, we now have human interventional studies, which we’ll explore next.

Stay tuned for The Health Benefits of Sorghum.

Should we all be seeking gluten-free grains? See related posts below.