Back in the early 1980s, a pathologist in Florida suggested that the reason premenopausal women are protected from heart disease is that they have lower stores of iron in their body. Since oxidized cholesterol is “important in atherosclerosis, and oxidation is catalyzed by iron,” might the lower iron stores of menstruating women reduce their risk of coronary heart disease? “The novel insight suggesting that the longevity enjoyed by women over men might relate to the monthly loss…of blood is remarkable,” but is it true? I discuss this in my video Donating Blood to Prevent Heart Disease?.

The consumption of heme iron—the iron found in blood and muscle—is associated with increased risk of heart disease. Indeed, “an increase in heme iron intake of 1 mg/day appeared to be significantly associated with a 27% increase in risk of CHD,” coronary heart disease. But, heme iron is found mainly in meat, so “it is possible that some constituents other than heme iron in meat such as saturated fat and cholesterol are responsible” for the apparent link between heme iron and heart disease. If only we could find a way to get men to menstruate, then we could put the theory to the test. What about blood donations? Why just lose a little blood every month when you can donate a whole unit at a time?

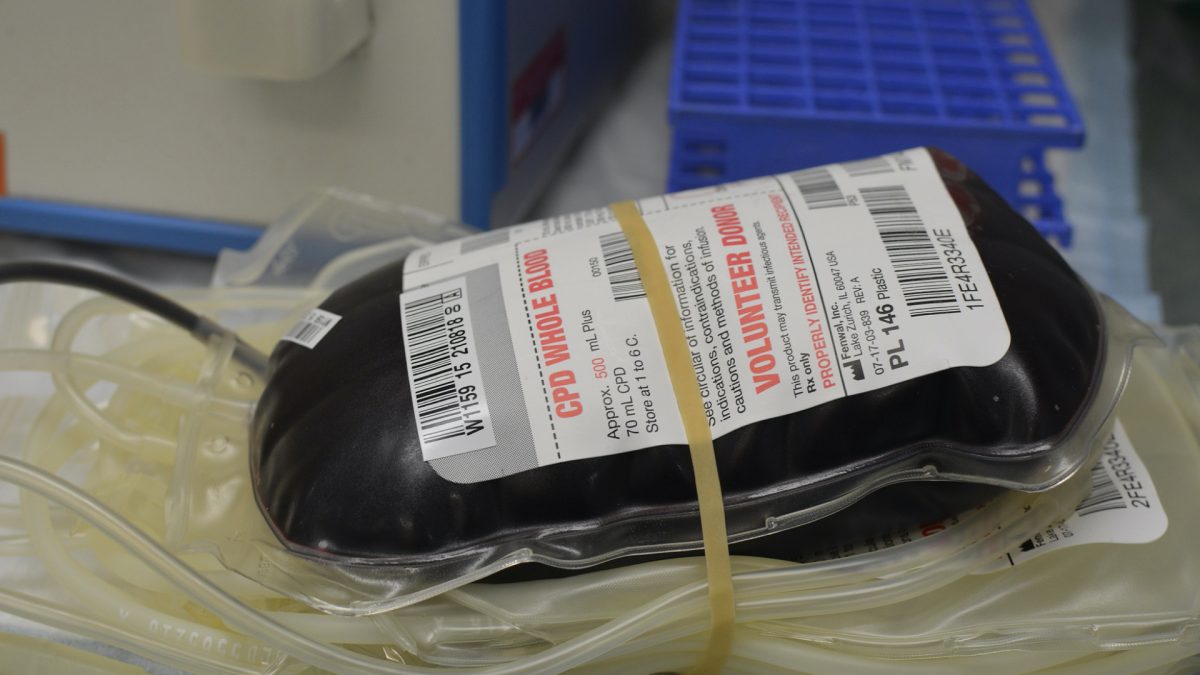

A study in Nebraska suggested that blood donors were at “reduced risk of cardiovascular events,” but another study in Boston failed to show any connection. To definitively resolve the question, we would really have to put it to the test: Take people at high risk for heart disease, randomly bleed half of them, and then follow them over time and see who gets more heart attacks. Maybe it could turn “bloodletting” from the past into “bleeding-edge technology.” In fact, that was actually what was suggested in the original paper as a way to test this idea: “The depletion of iron stores by regular phlebotomy could be the experimental system for testing this hypothesis…”

It took 20 years, but researchers finally did it. Why did it take so long? There isn’t much money in bloodletting these days. I suppose the leech lobby just isn’t as powerful as it used to be.

What did the researchers find? It didn’t work. The blood donors ended up having the same number of heart attacks as the non-donor group. Something extraordinary did happen, however: The cancer rates dropped. There was a 37 percent reduction in overall cancer incidence, and those who developed cancer had a significantly reduced risk of death. An editorial in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute responded with near disbelief, saying the “results almost seem to be too good to be true.” “Strikingly,” they started to see cancer reduction benefits within six months, after giving blood just once. As the study progressed, the cancer death rates started to diverge within just six months, as you can see at 2:46 in my video, but this is consistent with the spike in cancer rates we see within only six months of getting a blood transfusion. Is it possible that influx of iron accelerated the growth of hidden tumors?

I continue this wild story in my video Donating Blood to Prevent Cancer?.

What if you feel faint when you give blood? Don’t worry. I’ve got you covered. Check out How to Prevent Fainting.

What might iron have to do with disease? See The Safety of Heme vs. Non-Heme Iron and Risk Associated with Iron Supplements.

In health,

Michael Greger, M.D.

PS: If you haven’t yet, you can subscribe to my free videos here and watch my live presentations:

- 2012: Uprooting the Leading Causes of Death

- 2013: More Than an Apple a Day

- 2014: From Table to Able: Combating Disabling Diseases with Food

- 2015: Food as Medicine: Preventing and Treating the Most Dreaded Diseases with Diet

- 2016: How Not To Die: The Role of Diet in Preventing, Arresting, and Reversing Our Top 15 Killers

- 2019: Evidence-Based Weight Loss