Fiber and Colon Cancer Protection

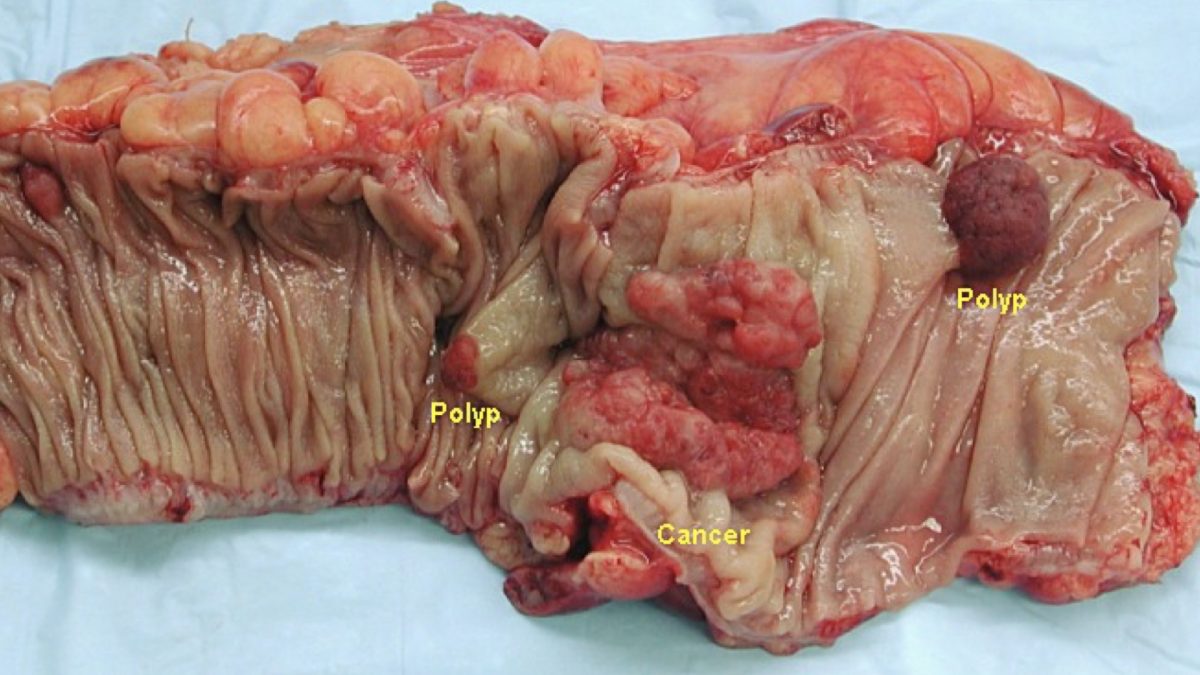

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cause of cancer death in the world. Thankfully, the good bacteria in our gut take the fiber we eat and make short-chain fatty acids, like butyrate, that protect us from cancer. We take care of them, and they take care of us. If we do nothing to colon cancer cells, they grow. That’s what cancer does. But if we expose the colon cancer cells to the concentration of butyrate our good bacteria make in our gut when we eat fiber, the growth is stopped in its tracks. If, however, the butyrate stops, if we eat healthy for only one day and then turn off the fiber the next, the cancer can resume its growth. So, ideally, we have to eat a lot of fiber-rich foods—meaning whole plant foods—every day.

What about the populations, like those in modern sub-Saharan Africa, where they don’t eat a lot of fiber yet still rarely get colon cancer? Traditionally, they used to eat a lot of fiber, but now their diet is centered around highly refined corn meal, which is low in fiber—yet they still have low colon cancer rates. Why? This was explained by the fact that while they may be lacking protective factors like fiber, they are also lacking cancer-promoting factors like animal protein and fat. But are they really lacking protective factors?

If you measure the pH of their stools, the black populations in South Africa have lower pH, which means more acidic stools, despite comparable fiber intakes. That’s a good thing and may account for the lower cancer rates. But, wait a second. Low colon pH is caused by short-chain fatty acids, which are produced by our good bacteria when they eat fiber, but they weren’t eating any more fiber, suggesting there was something else in addition to fiber in their diets that was feeding their flora. And, indeed, despite low fiber intake, the bacteria in their colon were still churning out short-chain fatty acids like crazy. But if their bacteria weren’t eating fiber, what were they eating? Resistant starch. “[T]he method of cooking and eating the maize [corn] meal as a porridge results in an increase in resistant starch, which acts in the same way as fiber in the colon,” as a prebiotic, a food for our good bacteria to produce the same cancer-preventing, short-chain fatty acids.

Resistant Starch and Colon Cancer

As I discuss in my video Resistant Starch and Colon Cancer, “[r]esistant starch is any starch…that is not digested and absorbed in the upper digestive tract [our small intestine] and, so, passes into the large bowel,” our colon, to feed our good bacteria. When you boil starches and then let them cool, some of the starch can recrystallize into a form resistant to our digestive enzymes. So, we can get resistant starch eating cooled starches, such as pasta salad, potato salad, or cold cornmeal porridge. “This may explain the striking differences in colon cancer rates.” Thus, they were feeding their good bacteria after all, but just with lots of starch rather than fiber. “Consequently, a high carbohydrate diet may act in the same way as a high fiber diet.” Because a small fraction of the carbs make it down to our colon, the more carbs we eat, the more butyrate our gut bacteria can produce.

Indeed, countries where people eat the most starch have some of the lowest colon cancer rates, so fiber may not be the only protective factor. Only about 5 percent of starch may reach the colon, compared to 100 percent of the fiber, but we eat up to ten times more starch than fiber, so it can potentially play a significant role feeding our flora.

Carcinogens in Meat

So, the protection Africans enjoy from cancer may be two-fold: a diet high in resistant starch and low in animal products. Just eating more resistant starch isn’t enough. Meat contains or contributes to the production of presumed carcinogens, such as N-nitroso compounds. A study divided people into three groups: one was on a low-meat diet, the second was on a high-meat diet including beef, pork, and poultry, and the third group was on the same high-meat diet but with the addition of lots of resistant starch. The high-meat groups had three times more of these presumptive carcinogens and twice the ammonia in their stool than the low-meat group, and the addition of the resistant starch didn’t seem to help. This confirms that “exposure to these compounds is increased with meat intake,” and 90 percent are created in our bowel. So, it doesn’t matter if we get nitrite-free, uncured fresh meat; these nitrosamines are created from the meat as it sits in our colon. This “may help explain the higher incidence of large bowel cancer in meat-eating populations,” along with the increase in ammonia—neither of which could be helped by just adding resistant starch on top of the meat.

“[T]he deleterious effects of animal products on colonic metabolism override the potentially beneficial effects of other protective nutrients.” So, we should do a combination of less meat and more whole plant foods, along with exercise, not only for our colon, but also for general health.

This is a follow-up to my video Is the Fiber Theory Wrong?.

What exactly is butyrate? See:

- Bowel Wars: Hydrogen Sulfide vs. Butyrate

- Prebiotics: Tending Our Inner Garden

- Treating Ulcerative Colitis with Diet

- Boosting Good Bacteria in the Colon Without Probiotics

For videos on optimizing your gut flora, see:

- Microbiome: The Inside Story

- What’s Your Gut Microbiome Enterotype?

- How to Change Your Enterotype

- Gut Dysbiosis: Starving Our Microbial Self

- How to Reduce Carcinogenic Bile Acid Production

- Effect of Sucralose (Splenda) on the Microbiome

Interested in more on preventing colon cancer? See:

- Starving Cancer with Methionine Restriction

- Stool pH and Colon Cancer

- Solving a Colon Cancer Mystery

If you’re eating healthfully, do you need a colonoscopy? Find out in Should We All Get Colonoscopies Starting at Age 50?.

When regular starches are cooked and then cooled, some of the starch recrystallizes into resistant starch. For this reason, pasta salad can be healthier than hot pasta, and potato salad can be healthier than a baked potato. Find out more in my video Getting Starch to Take the Path of Most Resistance.

In health,

Michael Greger, M.D.

PS: If you haven’t yet, you can subscribe to my free videos here and watch my live, year-in-review presentations:

- 2012: Uprooting the Leading Causes of Death

- 2013: More Than an Apple a Day

- 2014: From Table to Able: Combating Disabling Diseases with Food

- 2015: Food as Medicine: Preventing and Treating the Most Dreaded Diseases with Diet

- 2016: How Not To Die: The Role of Diet in Preventing, Arresting, and Reversing Our Top 15 Killers