A Mayo Clinic visualization tool can help you decide if cholesterol-lowering statin drugs are right for you.

“Physicians have a duty to inform their patients about the risks and benefits of the interventions available to them. However, physicians rarely communicate with methods that convey absolute information, such as numbers needed to treat, numbers needed to harm, or prolongation of life, despite patients wanting this information.” That is, for example, how many people are actually helped by a particular drug, how many are actually hurt by it, or how much longer the drug will enable you to live, respectively.

If doctors inform patients only about the relative risk reduction—for example, telling them a pill will cut their risk of heart attacks by 34 percent—nine out of ten agree to take it. However, give them the same information framed as absolute risk reduction—“1.4% fewer patients had heart attacks”—then those agreeing to take the drug drops to only four out of ten. And, if they use the number needed to treat, only three in ten patients would agree to take the pill. So, if you’re a doctor and you really want your patient to take the drug, which statistic are you going to use?

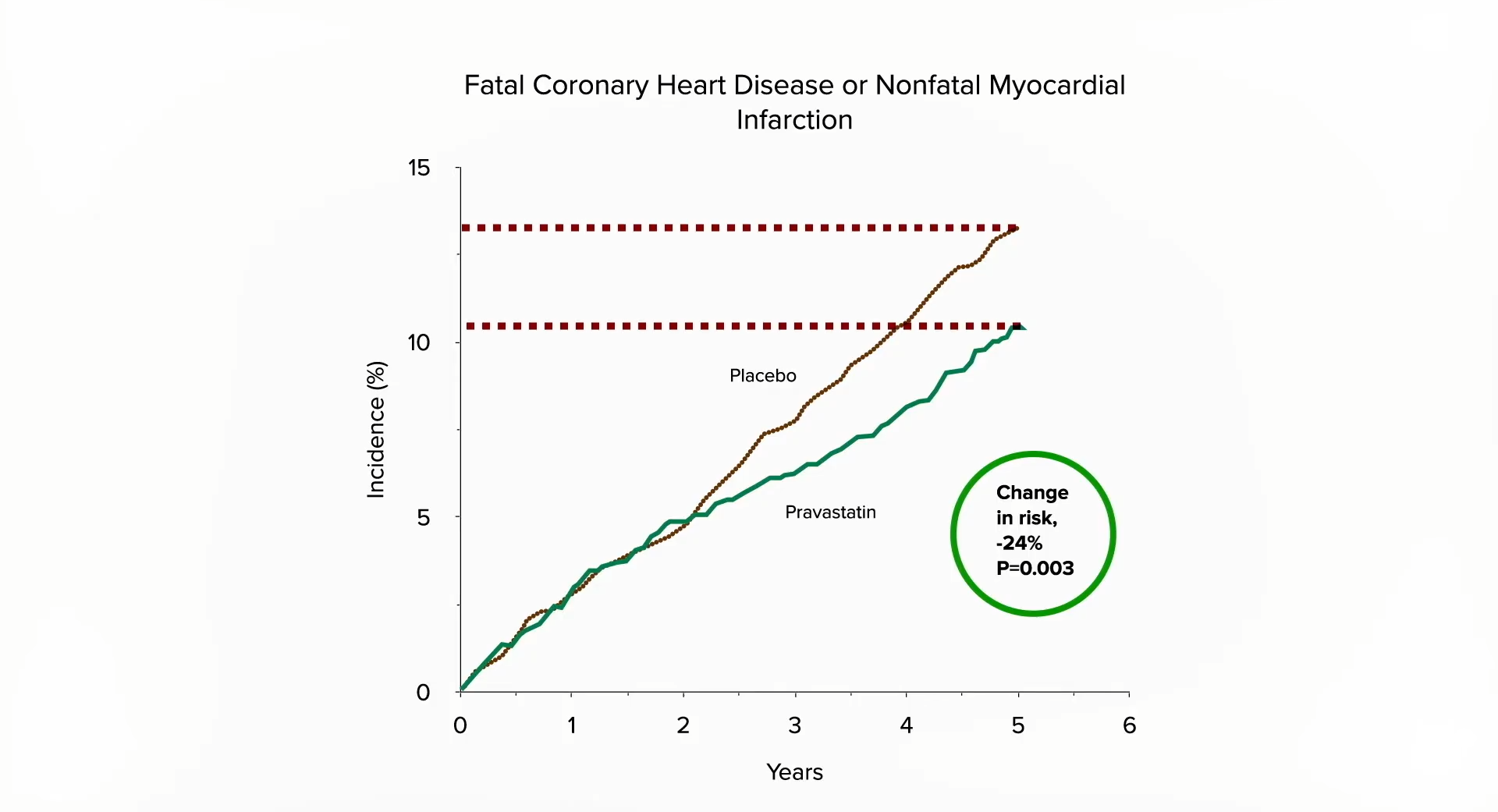

The use of relative risk stats to inflate the benefits and absolute risk stats to downplay any side effects has been referred to as “statistical deception.” To see how one might spin a study to accomplish this, let’s look at an example. As you can see below and at 1:49 in my video, The True Benefits vs. Side Effects of Statins, there is a significantly lower risk of the incidence of heart attack over five years in study participants randomized to a placebo compared to those getting the drug. If you wanted statins to sound good, you’d use the relative risk reduction (24 percent lower risk). If you wanted statins to sound bad, you’d use the absolute risk reduction (3 percent fewer heart attacks).

Then you could flip it for side effects. For example, the researchers found that 0.3 percent (1 out of 290 women in the placebo group) got breast cancer over five years, compared to 4.1 percent (12 out of 286) in the statin group. So, a pro-statin spin might be a 24 percent drop in heart attack risk and only 3.8 percent more breast cancers, whereas an anti-statin spin might be only 3 percent fewer heart attacks compared to a 1,267 percent higher risk of breast cancer. Both portrayals are technically true, but you can see how easily you could manipulate people if you picked and chose how you were presenting the risks and benefits. So, ideally, you’d use both the relative risk reduction stat and the absolute risk reduction stat.

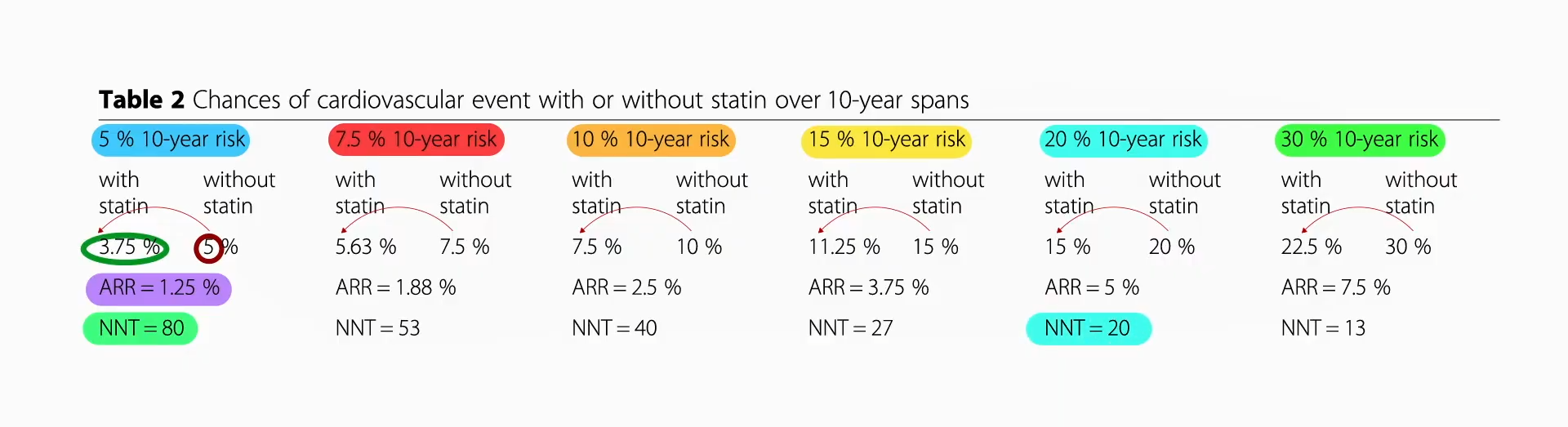

In terms of benefits, when you compile many statin trials, it looks like the relative risk reduction is 25 percent. So, if your ten-year risk of a heart attack or stroke is 5 percent, then taking a statin could lower that from 5 percent to 3.75 percent, for an absolute risk reduction of 1.25 percent, or a number needed to treat of 80, meaning there’s about a 1 in 80 chance that you’d avoid a heart attack or stroke by taking the drug for the next ten years. As you can see, as your baseline risk gets higher and higher, even though you have that same 25 percent risk reduction, your absolute risk reduction gets bigger and bigger. And, with a 20 percent baseline risk, that means you have a 1 in 20 chance of avoiding a heart attack or stroke over the subsequent decade if you take the drug, as seen below and at 3:31 in my video.

So, those are the benefits. In terms of risk, that breast cancer finding appears to be a fluke. Put together all the studies, and “there was no association between use of statins and the risk of cancer.” In terms of muscle problems, estimates of risk range from approximately 1 in 1,000 to closer to 1 in 50.

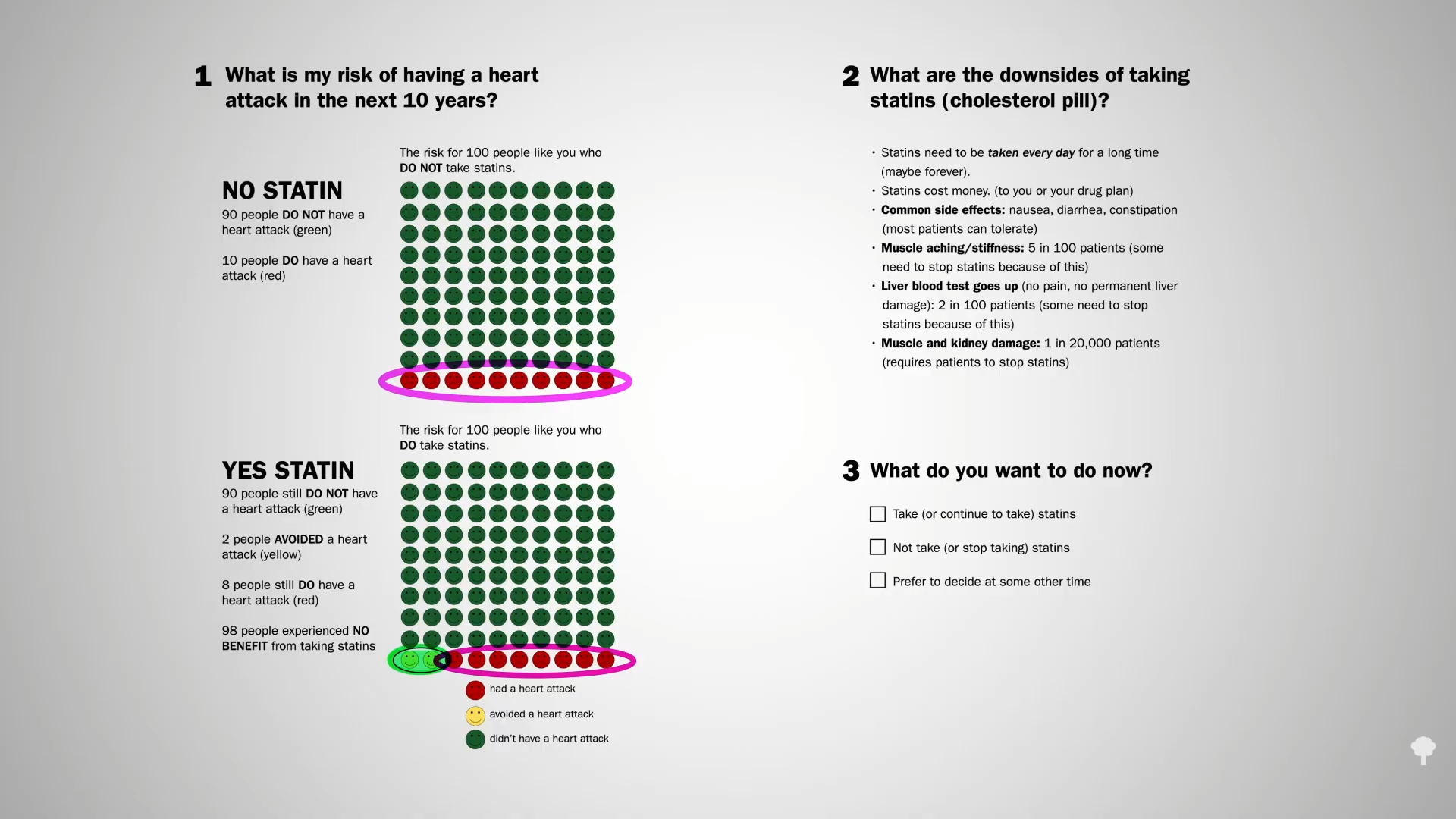

If all those numbers just blur together, the Mayo Clinic developed a great visualization tool, seen below and at 4:39 in my video.

For those at average risk, 10 people out of 100 who do not take a statin may have a heart attack over the next ten years. If, however, all 100 people took a statin every day for those ten years, 8 would still have a heart attack, but 2 would be spared, so there’s about a 1 in 50 chance that taking the drug would help avert a heart attack over the next decade. What are the downsides? The cost and inconvenience of taking a pill every day, which can cause some gastrointestinal side effects, muscle aching, and stiffness in about 5 percent, reversible liver inflammation in 2 percent, and more serious damage in perhaps 1 in 20,000 patients.

Note that the two happy faces in the bottom left row of the YES STATIN chart represent heart attacks averted, not lives saved. The chance that a few years of statins will actually save your life if you have no known heart disease is about 1 in 250.

If you want a more personalized approach, the Mayo Clinic has an interactive tool that lets you calculate your ten-year risk. You can get there directly by going to bit.ly/statindecision.