Ozempic

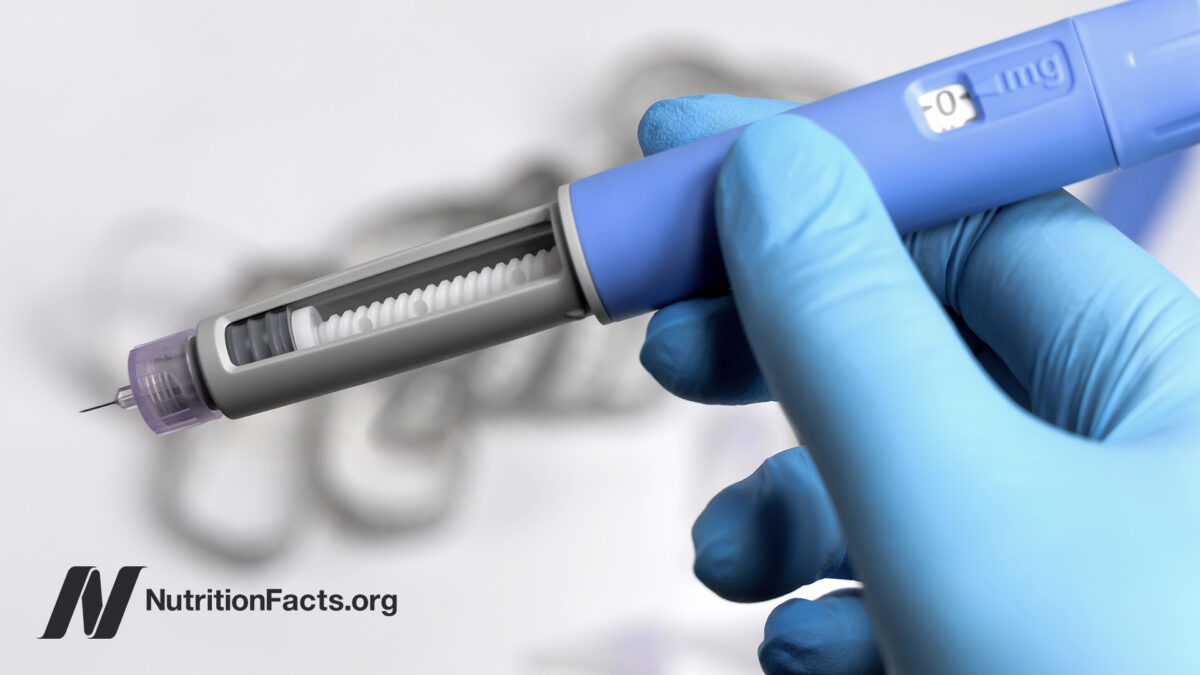

Ozempic and others in a new class of weight-loss drugs have been called “the medical sensation of the decade.” Are they worthy of all the hype?

A naturally occurring hormone in our body, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) plays a role in regulating our blood sugar, appetite, and digestion. Our gastrointestinal tract releases more than 20 different peptide hormones, including GLP-1. The primary stimuli for secreting GLP-1 are meals rich in fats and carbohydrates, and GLP-1’s main action is to signal satiety to the brain. It also slows our digestion. Delaying the rate at which food leaves our stomach not only helps us feel fuller for longer, but also helps with our blood sugar control. When GLP-1 or an agonist is dripped into people’s veins, appetite is reduced, leading to markedly reduced food consumption—a decrease in caloric intake by as much as 25 to 50 percent.

Our GLP-1 hormone acts as an appetite suppressant by targeting parts of the brain responsible for hunger and cravings. GLP-1-secreting cells don’t only line our intestines; they’re also in our brains. These new anti-obesity drugs, including Ozempic, are GLP-1 agonists, mimicking the hormone’s action by binding to GLP-1 receptors.

In a way, GLP-1 agonist drugs work like birth control pills. The Pill mimics placental hormones, thereby tricking our body into thinking we’re pregnant all the time. Ozempic-type drugs mimic GLP-1, thereby tricking our body into thinking we’re eating all the time. That’s how it dials down our hunger drive.

In the longest trial to date, more than 17,000 individuals were randomized to injections of either high-dose semaglutide or placebo for four years. Overall, those on the drug lost 9 percent more body weight than those in the placebo group, but all the weight was lost in the first 65 weeks. Even though they continued to get injected every week for three more years, they didn’t lose any more weight over the subsequent 143 weeks. And, as soon as we stop taking the drugs, our full appetite resumes and we start regaining the weight we initially lost.

The most common drug side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. Gallbladder issues are another side effect; excess cholesterol shed from fat cells can crystalize in our bile like rock candy, forming gallstones. Rare but serious adverse effects are also emerging. The package inserts for both semaglutide and tirzepatide list a series of “warnings and precautions” that include thyroid tumors, acute inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), acute gallbladder disease, acute kidney injury (that may stem from dehydration due to excess vomiting or diarrhea), allergic reactions, a heightened risk of bottoming out blood sugars while on blood sugar–lowering medications, worsening eye disease for those with type 2 diabetes, an increase in heart rate requiring monitoring, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors.,

At this time, the long-term harms or benefits are unknown because some of these drugs and dosing schedules are so new. To complicate matters, the American Academy of Pediatrics has suggested offering these drugs for teens and even tweens as young as age 12. These drugs work by acting on the brain, so who knows what effect they might have on childhood development and beyond if young people end up taking them for the rest of their lives. Although we now have evidence of near-term benefit over a few years, we cannot assume long-term safety until it has been demonstrated.

We don’t need to take GLP-1-mimicking drugs. Not only can the ingestion of a plant-based meal more than double GLP-1 secretion, compared to a meat meal, but plant-based diets can also cause weight loss by boosting our resting metabolic rate and incorporating “calorie-trapping” high-fiber foods that flush calories away. The largest study of people eating strictly plant-based found they are about 35 pounds lighter on average, and the most effective weight-loss diet without portion restriction that was ever published in the peer-reviewed medical literature was a whole food, plant-based dietary intervention.

However, obesity can so dramatically decrease one’s lifespan, reducing life expectancy as much as six or seven years, that for those unwilling or unable to treat the cause of their obesity, these drugs, like bariatric surgery, should be considered as a last resort.

Image Credit: Unsplash

Popular Videos for Ozempic

Why Do Most Users Quit Ozempic and What Happens When You Stop?

Why does weight loss plateau on GLP-1 drugs, and why do most stop using them...

How to Control the Side Effects (Including “Ozempic Face”) of GLP-1 Drugs

How might we mitigate the gastrointestinal and muscle loss side effects of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs?

Is Ozempic (Semaglutide) Safe? Does It Increase Cancer Risk?

How common are serious potential side effects of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs, such as suicide, pancreatitis,...

Comparing the Benefits and Side Effects of Ozempic (Semaglutide)

Obesity can be so devastating to our health that the downsides of any effective drug...

Natural Ozempic Alternatives: Boosting GLP-1 with Diet and Lifestyle

Certain spices and the quinine in tonic water can boost GLP-1, but at what cost?

A Plant-Based Diet for Weight Loss: Boosting GLP-1 and Restoring Our Natural Satiety Circuit

Why does our natural GLP-1 satiety mechanism fail, and what can we do about it?

Using Prebiotics, Intact Grains, Thylakoids, and Greens to Boost Our GLP-1 for Weight Loss

Boost our natural satiety hormone GLP-1 through out diet.

Obesity: Is a GLP-1 Deficiency Its Cause, and How to Treat It Without Ozempic and Other Drugs

What is a safer and cheaper way to lose weight than GLP-1 drugs?All Videos for Ozempic

-

Obesity: Is a GLP-1 Deficiency Its Cause, and How to Treat It Without Ozempic and Other Drugs

What is a safer and cheaper way to lose weight than GLP-1 drugs?

-

Using Prebiotics, Intact Grains, Thylakoids, and Greens to Boost Our GLP-1 for Weight Loss

Boost our natural satiety hormone GLP-1 through out diet.

-

A Plant-Based Diet for Weight Loss: Boosting GLP-1 and Restoring Our Natural Satiety Circuit

Why does our natural GLP-1 satiety mechanism fail, and what can we do about it?

-

Natural Ozempic Alternatives: Boosting GLP-1 with Diet and Lifestyle

Certain spices and the quinine in tonic water can boost GLP-1, but at what cost?

-

Comparing the Benefits and Side Effects of Ozempic (Semaglutide)

Obesity can be so devastating to our health that the downsides of any effective drug would have to be significant to outweigh its weight-loss benefits.

-

Is Ozempic (Semaglutide) Safe? Does It Increase Cancer Risk?

How common are serious potential side effects of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs, such as suicide, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, thyroid cancer, and pancreatic cancer?

-

How to Control the Side Effects (Including “Ozempic Face”) of GLP-1 Drugs

How might we mitigate the gastrointestinal and muscle loss side effects of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs?

-

Why Do Most Users Quit Ozempic and What Happens When You Stop?

Why does weight loss plateau on GLP-1 drugs, and why do most stop using them within just three months even if they can afford them?

-

GLP-1 Weight-Loss Drugs Like Ozempic (Semaglutide): How Do They Work? Are They Effective?

What is the hormone GLP-1, what separates GLP-1 mimics from previous weight-loss drugs, and how much weight may be lost before weight loss plateaus?