Common drugs, foods, and beverages can disrupt the integrity of our intestinal barrier, causing a leaky gut.

Intestinal permeability, the leakiness of our gut, may be a new target for both disease prevention and therapy. With all its tiny folds, our intestinal barrier covers a surface of more than 4,000 square feet—that’s bigger than a tennis court—and requires about 40% of our body’s total energy expenditure to maintain.

There is growing evidence implicating “the disruption of intestinal barrier integrity” in the development of a number of conditions, including celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Researchers measured intestinal permeability using blue food coloring. It remained in the gut of healthy participants but was detected in the blood of extremely sick patients with sepsis with a damaged gut barrier. You don’t have to end up in the ICU to develop a leaky gut, though. Simply taking some aspirin or ibuprofen can do the trick.

Indeed, taking two regular aspirin (325 mg tablets) or two extra-strength aspirin (500 mg tablets) just once can increase the leakiness of our gut. These results suggest that even healthy people should be cautious when using aspirin, as it may cause gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction.

What about buffered aspirin, an aspirin-antacid combination which theoretically “buffers” gastrointestinal irritation? It apparently doesn’t make any difference: Regular aspirin and Bufferin both produced multiple erosions in the inner lining of the stomach and intestine. Researchers put a scope down people’s throats and saw extensive erosions and redness inside 90% of those who took aspirin or Bufferin at their recommended doses. How many hours does it take for the damage to occur? None. It can happen within just five minutes. Acetaminophen, sold as Tylenol in the United States, may not lead to gastrointestinal damage and could be a better choice, unless you have problems with your liver. And rather than making things better, vitamin C supplements appeared to make the aspirin-induced increase in gut leakiness even worse.

Interestingly, this may be why NSAID drugs like aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen “are involved in up to 25% of food-induced anaphylaxis.” In other words, they are associated with over 10-fold higher odds of life-threatening food allergy attacks, presumably because these drugs increase the leakiness of the intestinal barrier, causing tiny food particles to slip into the bloodstream. But can exercise increase risk, too?

Strenuous exercise—for instance, an hour at 70% maximum capacity—may divert so much blood to the muscles and away from our internal organs that it may cause transient injury to our intestines, causing mild gut leakiness. But this can be aggravated if athletes take ibuprofen or any other NSAID drugs, which is unfortunately all too common.

Alcohol can also be a risk factor for food allergy attacks for the same reason—increasing gut leakiness. But cut out the alcohol, and our gut might heal up.

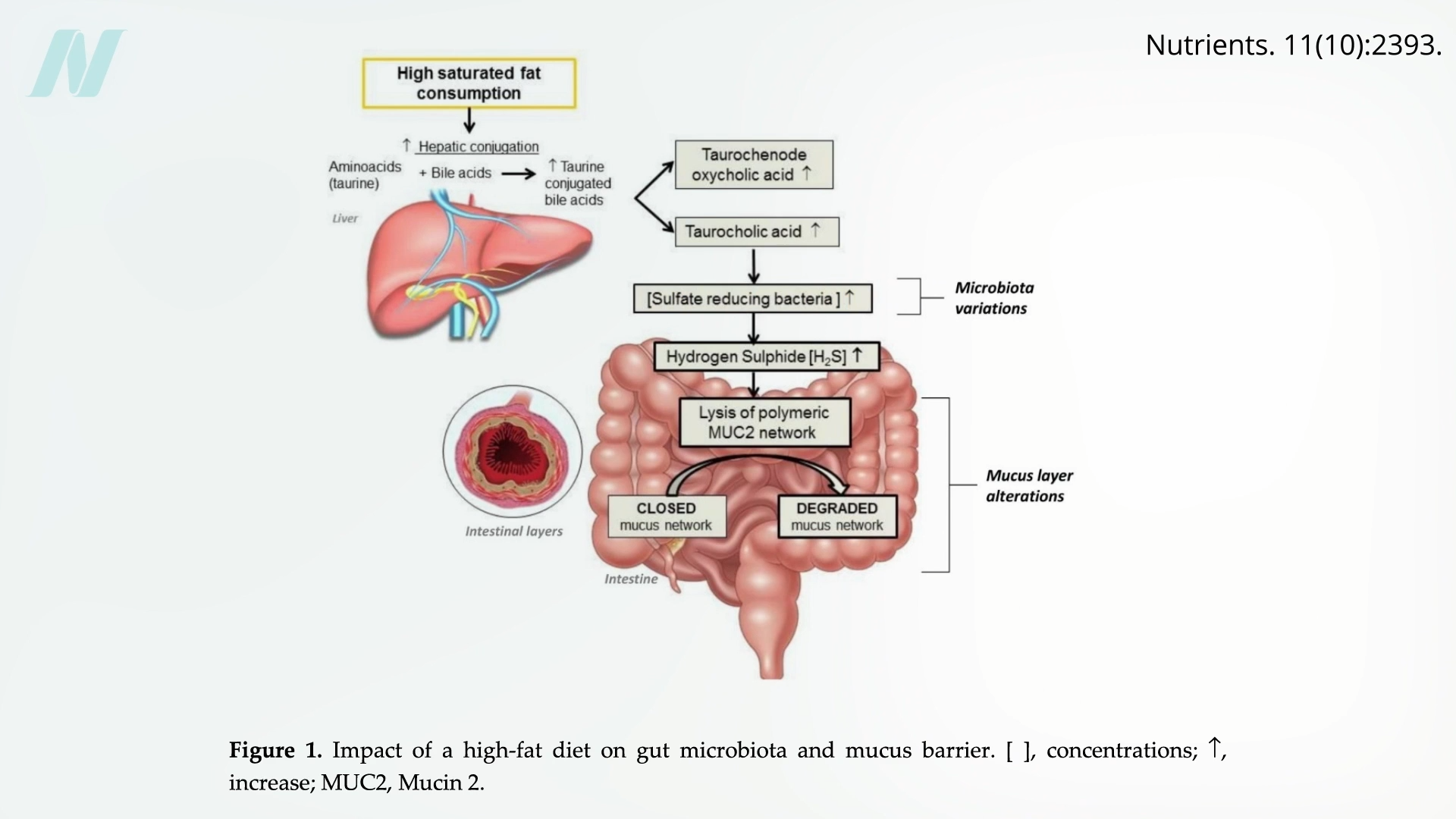

What other dietary components can make a difference? Elevated consumption of saturated fat, which is found in meat, dairy, and junk food, can cause the growth of bad bacteria that make the rotten-egg gas hydrogen sulfide, which can degrade the protective mucus layer. You can see the process below and at 3:21 in my video Avoid These Foods to Prevent a Leaky Gut.

It is said to be clear that high-fat diets in general have a negative impact on intestinal health by “disrupting the intestinal barrier system through a variety of mechanisms,” but most of the vast array of studies that cited the negative effects were done on lab animals or in a petri dish. Are people affected the same way? You don’t know for sure until you put it to the test.

Rates of obesity and other cardiometabolic disorders have increased rapidly alongside a transition from traditional lower-fat diets to higher-fat diets. We know a disturbance in our good gut flora has been shown to be associated with a high risk of many of these same diseases, and studies using rodents suggest that a high-fat diet “unbalances” the microbiome while impairing the gut barrier, resulting in disease. To connect all the dots, though, we need a human interventional trial—and we got one: a six-month randomized controlled-feeding trial on the effects of dietary fat on gut microbiota. It found that, indeed, higher fat consumption was associated with unfavorable changes in the gut microbiome and proinflammatory factors in the blood. Note that this wasn’t even primarily saturated fat, such as from meat and dairy. The researchers just replaced refined carbohydrates with refined fats—swapping out white rice and wheat flour for soybean oil. These findings suggest that countries westernizing their diets should advise against increasing dietary fat intake, while countries that have already adopted such diets should consider cutting down.

Doctor’s Note

For more on leaky gut, check out The Leaky Gut Theory of Why Animal Products Cause Inflammation and How to Heal a Leaky Gut with Diet.

I also talked about gut leakiness in my SIBO video: Friday Favorites: Tests, Fiber, and Low FODMAP for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO).