For more than a century, fasting has been used as a weight-loss treatment.

I’ve talked about the benefits of caloric restriction. Well, the greatest caloric restriction is getting no calories at all. Fasting has been branded “the next big weight loss fad,” but it has a long history throughout various spiritual traditions, practiced by Moses, Jesus, Muhammed, and Buddha. In 1732, a noted physician wrote, “He that eats till he is sick must fast till he is well.” About one in seven American adults today report taking that advice, “using fasting as a means to control body weight,” as I discuss in my video Benefits of Fasting for Weight Loss Put to the Test.

Case reports of the treatment of obesity through fasting date back more than a century in the medical literature. In 1915, two Harvard doctors indelicately described “two extraordinarily fat women,” one of whom “was a veritable pork barrel.” Their success led them to conclude that “successive moderate periods of starvation constitute a perfectly safe, harmless, and effective method for reducing the weight of those suffering from obesity.”

The longest-recorded fast, published in 1973, made it into the Guinness Book of World Records. To reach his ideal body weight, a 27-year-old man fasted for 382 days straight, losing 276 pounds, and managed to keep nearly all of it off. He was given vitamin and mineral supplements so he wouldn’t die, but no calories for more than a year. In the researchers’ acknowledgments, they thanked him “for his cheerful co-operation and steadfast application to the task of achieving a normal physique.”

In a U.S. Air Force study, more than 20 individuals at least 100 pounds overweight and most “unable to lose weight on previous diets” were fasted for as long as 84 days. Nine dropped out of the study, but the 16 who remained “were unequivocally successful” at losing 40 to 100 pounds. In the first four days, the subjects were noted as losing as much as four pounds a day, which “probably represents mostly fluid,” mostly water weight as the body starts to adapt. But, after a few weeks, they were steadily losing about a pound a day of mostly straight fat. The investigator described the starvation program as “a dramatic and exciting treatment for obesity.”

Of course, the single most successful diet for weight loss—namely no diet at all—is also the single least sustainable. What other diet can cure morbid obesity in a matter of months but practically be guaranteed to kill you within a year if you stick with it? The reason diets don’t work, almost by definition, is that people go on them, then they go off of them. Permanent weight loss is only achieved through permanent lifestyle change. So, what’s the point of fasting if you’re just going to go back to your regular diet and gain right back all of that lost weight?

Fasting proponents cite the psychological benefit of realigning people’s perceptions and motivation. Some individuals have resigned themselves to the belief that weight loss for them is somehow impossible. They may think “that they are ‘made differently’ from those of normal weight” in some way, and no matter what they do, the pounds don’t come off. But the rapid, unequivocal weight loss during fasting demonstrates to them that with a large enough change in eating habits, it’s not just possible, but inevitable. This morale boost may then embolden them to make better food choices once they resume eating.

The break from food may allow some an opportunity “to pause and reflect” on the role food is playing in their lives—not only the power it has over them but the power they have over it. In a fasting study entitled “Correction and Control of Intractable Obesity,” a patient’s personality was described as changing “from one of desperation, with abandonment of hope, to that of an eager extravert full of plans for a promising future.” She realized that her weight was within her own power to control. The researchers concluded: “This highly intellectual social worker has been returned to a full degree of exceptional usefulness.”

After a fast, newfound commitment to more healthful eating may be facilitated by a reduction in overall appetite reported post-fast, compared to pre-fast, at least temporarily. Even during a fast, hunger may start to dissipate within the first 36 hours. So, challenging people’s delusions about their exceptionality to the laws of physics—thinking they are “made differently”—with “short periods of total fasting may seem barbaric. In reality, this method of weight reduction is remarkably well tolerated by obese patients.” That seems to be a recurring theme in these published series of cases. In the influential paper “Treatment of Obesity by Total Fasting for up to 249 Days,” the researchers remarked that the “most surprising aspect of this study was the ease with which the prolonged fast was tolerated.” All of their patients “spontaneously commented on their increased sense of well-being, and in some, this amounted to frank euphoria.” They continued that, although “treatment by total fasting must only be prescribed under close medical supervision,” they “are convinced that it is the treatment of choice, certainly in cases of gross obesity.”

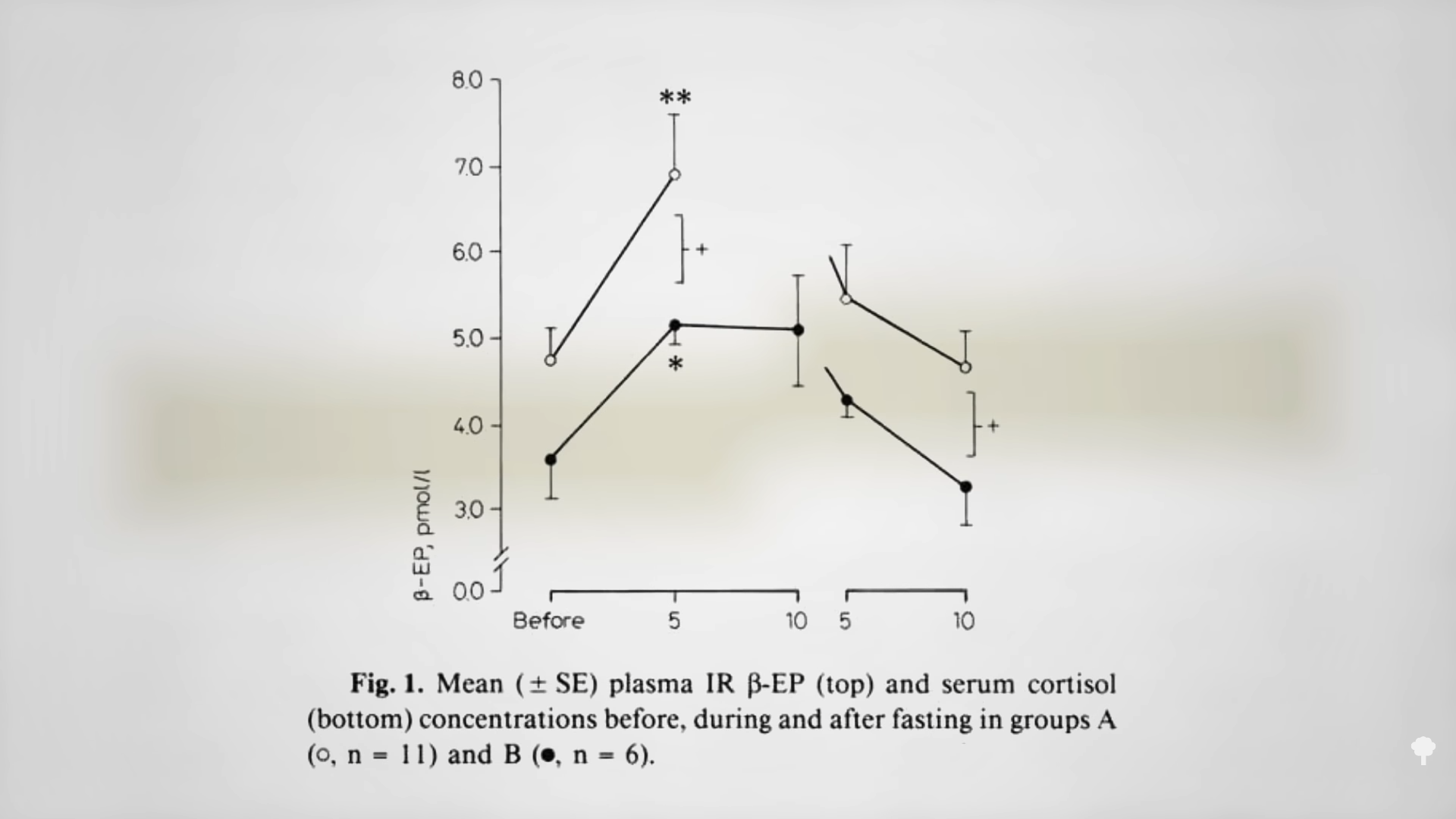

Fasting for a day can make people irritable and feel moody and distracted, but after a few days of fasting, many report feeling clear, elated, and alert—even euphoric. This may be in part due to the significant rise in endorphins that accompanies fasting, as you can see in the graph below and at 5:48 in my video. Mood enhancement during fasting is thought to perhaps represent an adaptive survival mechanism to motivate the food search. This positive outlook towards the future may then facilitate the behavioral change necessary to lock in some of the weight-loss benefits.

Is that what happens, though? Is fasting actually effective over the long term? There are articles with titles like “Death During Therapeutic Starvation for Obesity.” Is fasting even safe? We’ll find out next.

This is the sixth in a 14-part series on fasting for weight loss. In case you missed any of the others, see the related videos below.

My book How Not to Diet is all about weight loss. You can learn more about it and order it here.