What are the risks of contracting the brain parasite toxoplasma from cat litter or meat?

The brain parasite toxoplasma “is responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality,” that is, disease and death, “in the United States.” It holds second place as the leading cause of foodborne-related death in the United States, after Salmonella. The parasite can invade through the placenta, so it can be especially devastating during pregnancy, leading to miscarriages, blindness, or developmental delay. It can impair cognitive function in adults, too, which explains why those who are infected appear to be at increased risk for getting into traffic accidents, for instance. “Multiple lines of evidence indicate that chronic infections caused by T. gondii [toxoplasma] are likely associated with certain psychiatric disorders in human beings.” It may even increase the risk of developing leukemia. That’s a lot! So, how do you prevent it?

The parasite can get into the muscles, so we can contract it through meat consumption. We can also get infected through contact with feces from animals like cats. Thankfully, in cats, the “danger of infection exists only when the animal is actively shedding oocysts,” the tissue cysts formed by the parasite. Cats get it from eating infected rodents, so those “that are kept indoors, do not hunt, and are not fed raw meat are not likely to acquire T. gondii infection and therefore pose little risk to humans.” If neighborhood or feral cats are turning gardens or sandboxes at your local playground into a litter box, though, that could be a problem. As many as 6 percent of stray cats or those with outdoor access may be actively infected at any one time. They only shed the parasite for a few weeks, though, so if you adopt a cat from a shelter, they should be safe as long as they hadn’t just gone in.

Many women have heard about the cat connection but may be less aware of the risk of foodborne infection. Only about one in three may be aware that toxoplasma “may be found in raw or undercooked meat. Nevertheless, a high percentage of women indicated that they do not eat undercooked meat during pregnancy and that they practice good hygienic measures such as washing their hands after handling raw meat, gardening [where cats may be pooping] or changing cat litter.”

What’s the riskiest type of meat? “Cattle are not considered important hosts” for the parasite; it’s more pigs and poultry, as well as sheep and goats. The prevalence of infection among factory-farmed pigs varies from 0 to more than 90 percent. Ironically, “the likelihood of T. gondii infection in organic meat…appears to be higher than that in conventionally reared animals” because organically raised animals have outdoor access.

Who undercooks pork and poultry, though? Surprisingly, when it comes to reaching necessary pathogen-killing temperatures, about one in three Americans may undercook meat across the board. A single slice of ham, for example, can carry more than a thousand parasites per slice.

“Current meat inspection at slaughterhouse cannot detect the presence of T. gondii” parasites. There are tests you can perform, but “there is no widespread testing in meat inspection.” However, the risk from a single serving of meat is very small. The average probability of infection per serving of lamb, for example, was estimated to be about 1 in 67,000. The reason there are 16 times the number of cases attributed to pork consumption is not because pigs are more affected; we just happen to eat a lot more pork chops than lamb chops in the United States.

Is there anything we can do if we’re one of the approximately one in four Americans who has already been infected? Well, one of the problems with having these parasites in our brain is accelerated cognitive decline as we age. A study evaluated older adults every year for five years and found that the executive function of those testing positive for toxoplasma seemed to drop more quickly over time, as did a measure of their overall mental status. You can see this at 3:26 in my video How to Prevent Toxoplasmosis.

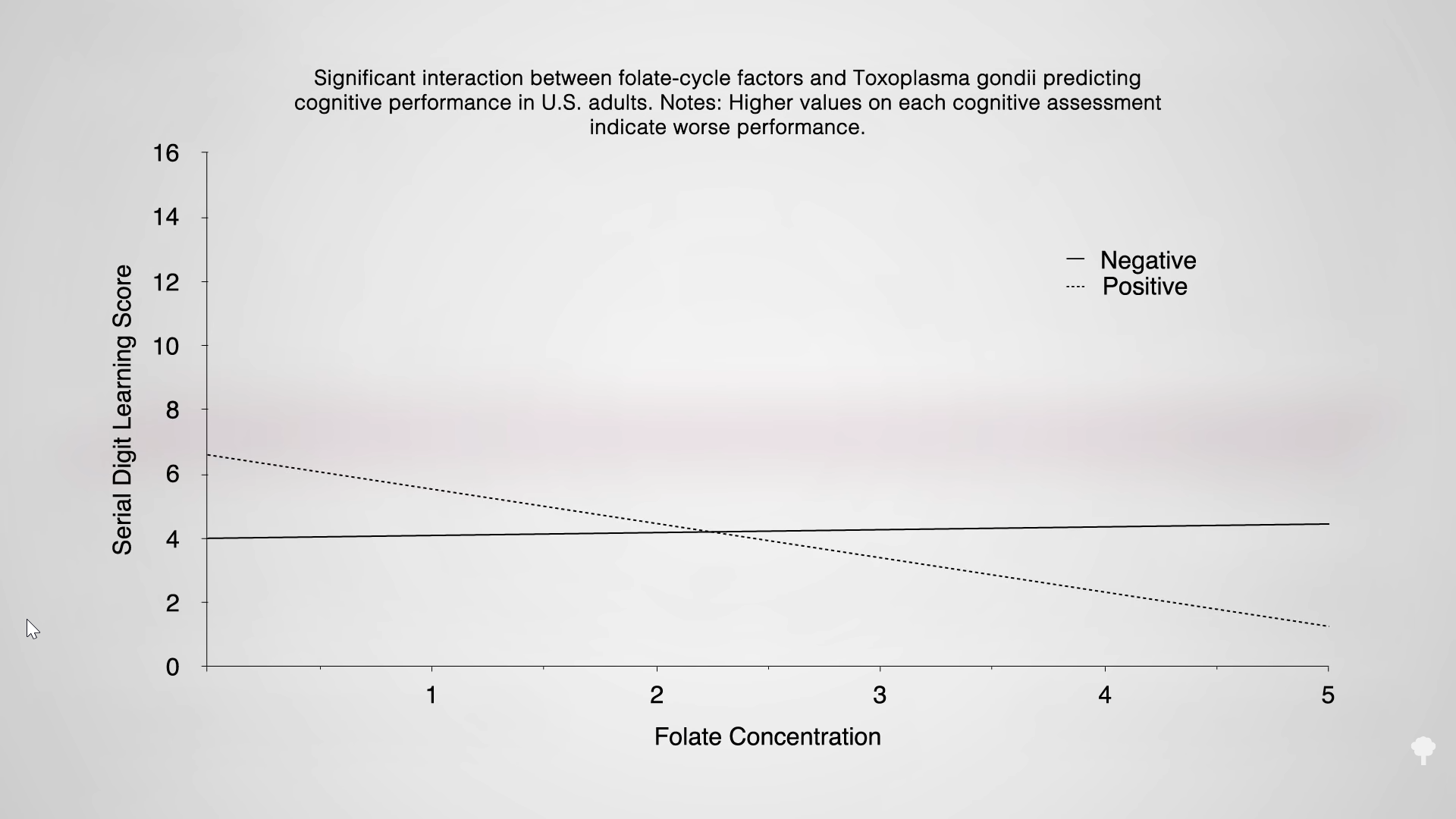

Reduced folate availability is also associated with cognitive decline, and the two may actually be related. “Recent evidence suggests that T. gondii may harvest folate from host neural cells”—directly from our nerve cells. So, beyond dopamine production, which is why we think toxo increases the risk of schizophrenia, the parasite may be sucking folate out of our brain. Enough to affect our cognitive functioning?

Perhaps so. In the graph below and at 4:04 in my video, you can see a chart measuring cognitive function across a range of folate concentrations. Among those who are uninfected, it doesn’t seem to matter whether they have a lot of folate or just a little; they obviously have enough either way. But those who are infected have worse scores at lower levels. The same with vitamin B12, so it’s important to get enough B12 and folate. For B12, the official recommendation is that all people aged 50 and older should start taking a vitamin B12 supplement or eat vitamin B12-fortified foods every day. And, anyone on a plant-based diet should start taking that advice at any age. Folate is found concentrated in beans and greens, so following my Daily Dozen recommendations will get you more than enough. For example, half a cup of cooked lentils gets you halfway there, as does three-quarters of a cup of cooked spinach.

Of course, toxoplasmosis is not the only reason to make sure you get enough vitamin B12. See, for example, Vitamin B12 Necessary for Arterial Health, and check out my optimum nutrient recommendations.

This was part of my four-video series on toxoplasmosis. If you missed any of the others, see: