What are the effects of aloe on radiation burns caused by cancer treatment and on the cancer itself?

“Worldwide attention was drawn to the possible value of gel prepared from Aloe arborescens [aloe] after the Second World War, when skin burns of victims of the nuclear bombs on Japan were successfully treated with its gel.” You don’t really know for sure, though, until you put it to the test.

As I discuss in my video Aloe for the Treatment of Advanced Metastatic Cancer, most radiation burns today are caused by doctors giving radiation treatments for cancer. These can cause “severe,” “painful,” and “scarring” skin reactions that can interfere with the therapy, but, sadly, we have yet to come up with good, “well-established prophylactic skin treatment measures to prevent radiation skin toxicity.” Enter aloe vera gel, which has been used on skin burns for centuries. So what happened when a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared aloe vera gel versus a placebo gel?

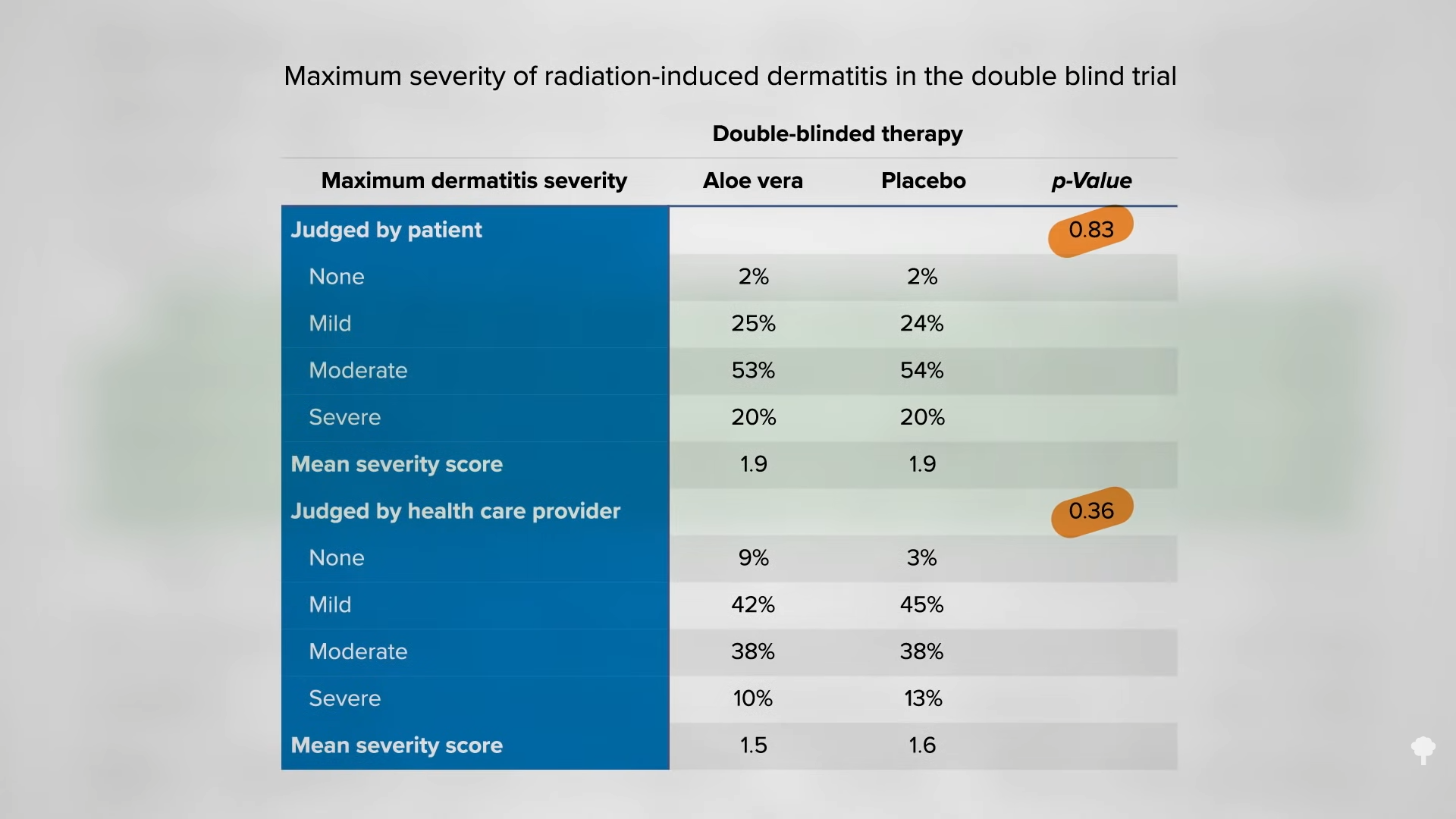

No benefit was found, as you can see below and at 1:02 in my video.

However, “after the completion of this double blind trial study, many involved clinicians felt that the patients participating in this trial had less dermatitis”—or skin inflammation—“than otherwise would have been expected. This raised the question of whether the placebo gel was causing some benefit (possibly due to skin lubrication).” So, to their credit, they ran a second experiment to see if aloe was better than nothing at all, and, once again, aloe appeared to have no effect at all. In both trials, the “severity scores were virtually identical,” meaning aloe vera gel simply didn’t work.

In an even larger trial, hundreds of patients were randomized to aloe vera gel or a plain skin lotion—not only during the radiation treatments, but even extending for two weeks after their completion. The result? The plain skin lotion placebo “was significantly better than the aloe vera gel in reducing dry desquamation [skin peeling] and pain related to treatment.” Yet again, aloe failed. Indeed, a systematic review of all such studies shows there is simply “no evidence from clinical trials to suggest that topical Aloe vera is effective” or helpful. Head and neck cancer patients suffer the additional burden of radiation damage to the lining of their mouth and throat, and aloe didn’t seem to help with that either.

Okay, so aloe may not help with cancer treatment, but what about helping with the cancer itself? In a petri dish, aloe “inhibits proliferation of human breast and cervical cancer cells” and also inhibits lung cancer cells, so is aloe vera “a natural cancer soother”? Unfortunately, “in vitro potency,” meaning petri dish studies, “often fails to translate to the clinic because of several factors,” including the fact that the compounds aren’t bioavailable enough to build up to test-tube levels within the tumor in the body. So, while “some studies suggest an antiproliferative effect on cancer cells in vitro…evidence from clinical trials is currently lacking”—that is, it was lacking…until 1998.

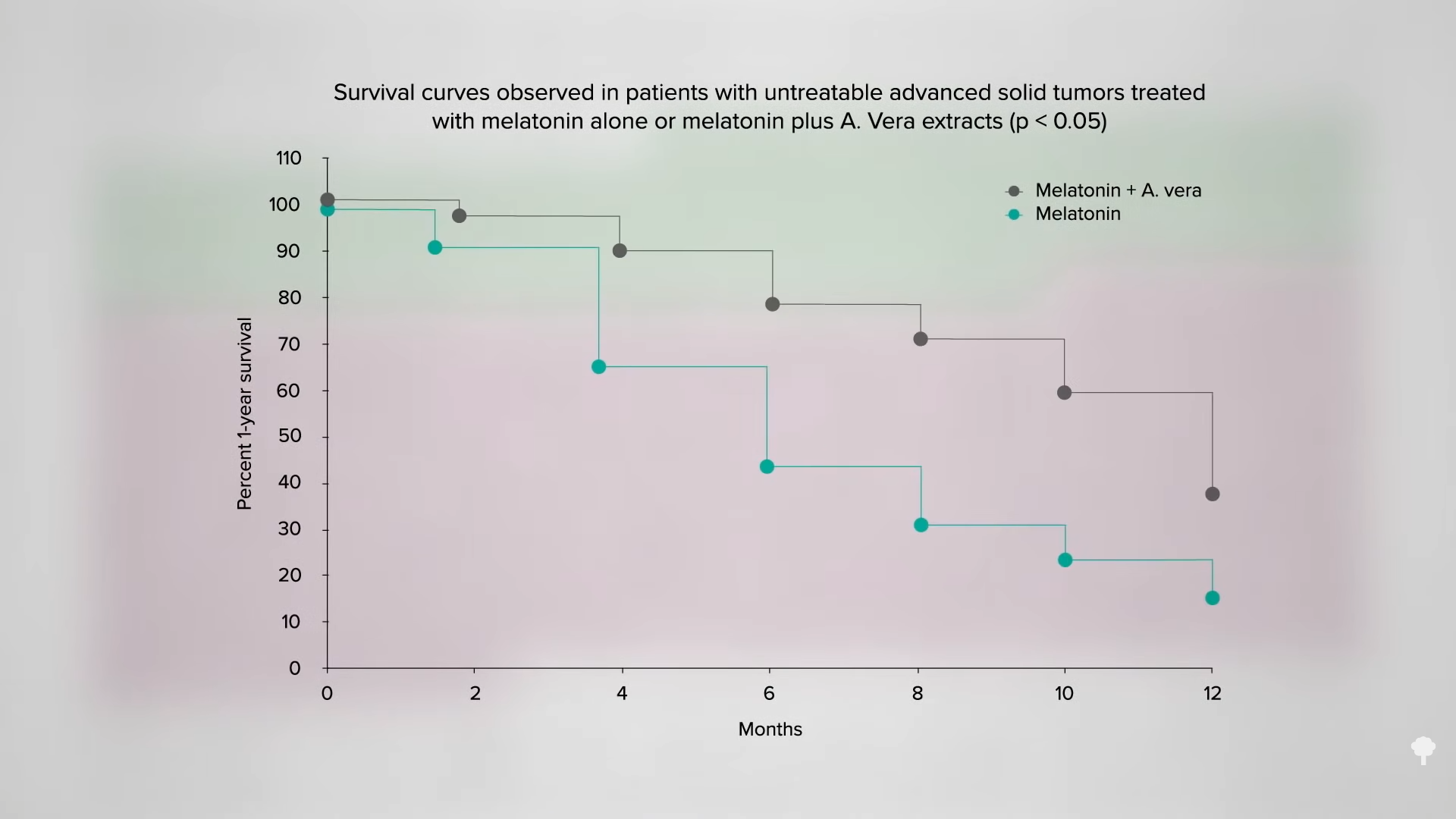

Fifty patients with advanced, untreatable cancer were treated either with daily melatonin, which researchers thought might boost anticancer immunity, or melatonin with about 20 drops of an aloe extract, prepared by soaking one part aloe leaves to nine parts 40-proof alcohol. And, the aloe group appeared to do better. They were nearly twice as likely to have either a partial response or at least some stabilization, and, the most important outcome, improved survival.

You can see the chart of the survival curves below and at 3:43 in my video.

Six months out, for example, 80 percent of the aloe group were still alive, whereas more than half of the non-aloe group had died. The researchers concluded that melatonin and aloe may be recommended to “patients with very advanced untreatable” cancers, since it didn’t seem to cause any bad side effects and, in fact, seemed to help. We don’t know if the aloe helps on its own, though, and a subsequent study by the same research group muddied the waters further by adding a third component, a tincture of myrrh. The main problem with these studies, however, is that they weren’t randomized. If sicker patients were intentionally—or unintentionally—placed in the non-aloe control group, that alone could explain the apparent aloe benefit. The problem is there had never been any randomized studies of aloe for advanced cancers, until 2009, which I cover in my video Can Aloe Cure Cancer?.