The industry responds to the charge that breakfast cereals are too sugary.

In 1941, the American Medical Association’s Council on Foods and Nutrition was presented with a new product, Vi-Chocolin, a vitamin-fortified chocolate bar, “offered ostensibly as a specialty product of high nutritive value and of some use in medicine, but in reality intended for promotion to the public as a general purpose confection, a vitaminized candy.” Surely, something like that couldn’t happen today, right? Unfortunately, that’s the sugary cereal industry’s business model.

As I discuss in my video Are Fortified Kids’ Breakfast Cereals Healthy or Just Candy?, nutrients are added to breakfast cereals “as a marketing gimmick to “create an aura of healthfulness…If those nutrients were added to soft drinks or candy, would we encourage kids to consume them more often?” Would we feed our kids Coke and Snickers for breakfast? We might as well spray cotton candy with vitamins, too. As one medical journal editorial read, “Adding vitamins and minerals to sugary cereals…is worse than useless. The subtle message accompanying such products is that it is safe to eat more.”

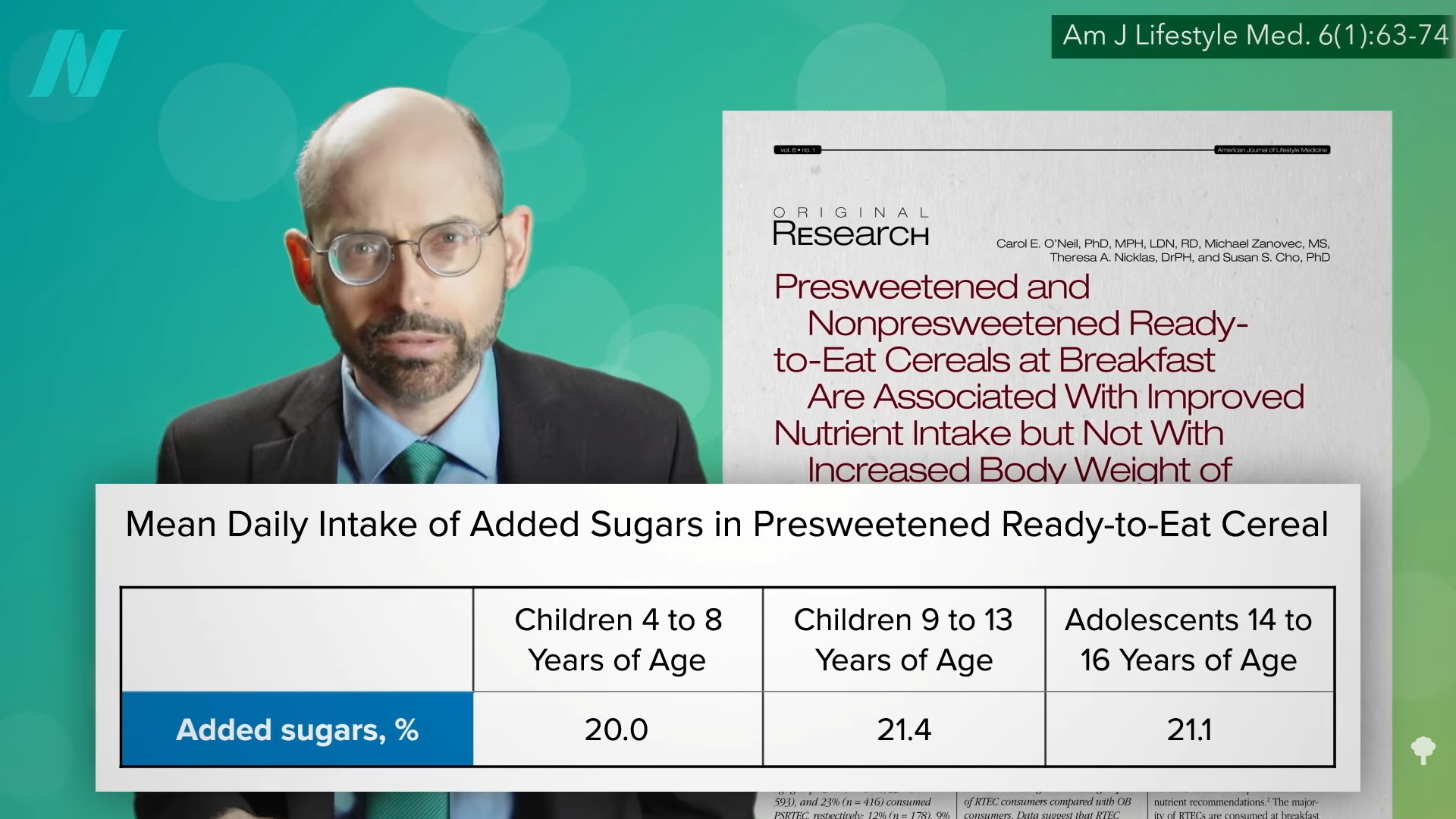

General Mills’ “Grow up strong with Big G kids’ cereals” ad campaign featured products like Lucky Charms, Trix, and Cocoa Puffs. That’s like the dairy industry promoting ice cream as a way to get your calcium. Kids who eat presweetened breakfast cereals may get more than 20 percent of their daily calories from added sugar, as you can see below and at 1:28 in my video.

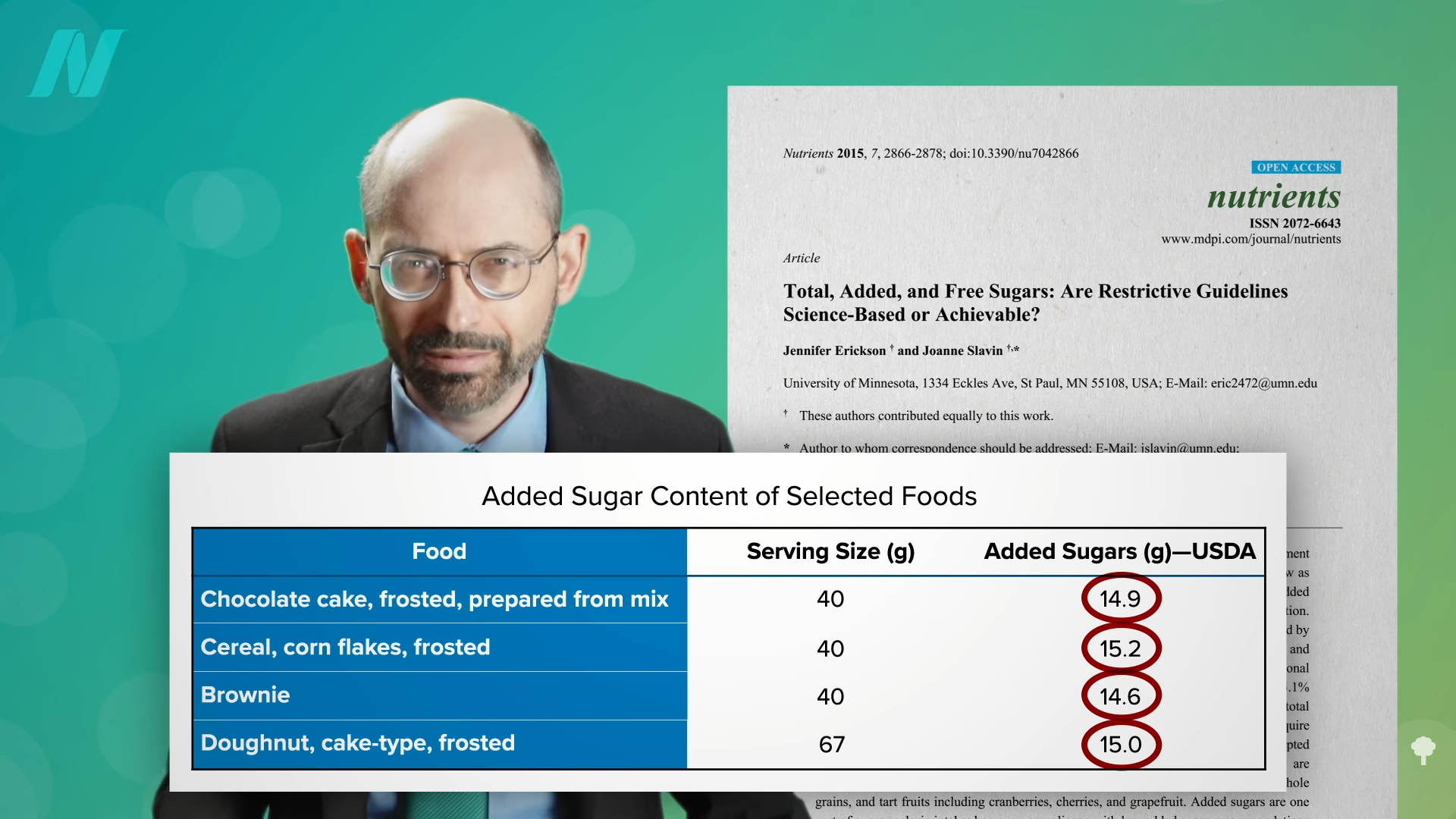

Most sugar in the American diet comes from beverages like soda, but breakfast cereals represent the third largest food source of added sugars in the diets of children and adolescents, wedged between candy and ice cream. On a per-serving basis, there is more added sugar in a cereal like Frosted Flakes than there is in frosted chocolate cake, a brownie, or even a frosted donut, as you can see below and at 1:48 in my video.

Kellogg’s and General Mills argue that breakfast cereals only contribute a “relatively small amount” of sugar to the diets of children, less than soda, for example. “This is a perfect example of the social psychology phenomenon of ‘diffusion of responsibility.’ This behavior is analogous to each restaurant in the country arguing that it should not be required to ban smoking because it alone contributes only a tiny fraction to Americans’ exposure to secondhand smoke.” In fact, “each source of added sugar…should be reduced.”

The industry argues that most of their cereals have less than 10 grams of sugar per serving, but when Consumer Reports measured how much cereal youngsters actually poured for themselves, they were found to serve themselves about 50 percent more than the suggested serving size for most of the tested cereals. The average portion of Frosted Flakes they poured for themselves contained 18 grams of sugar, which is 4½ teaspoons or 6 sugar packets’ worth. It’s been estimated that a “child eating one serving per day of a children’s cereal containing the average amount of sugar would consume nearly 1,000 teaspoons of sugar in a year.”

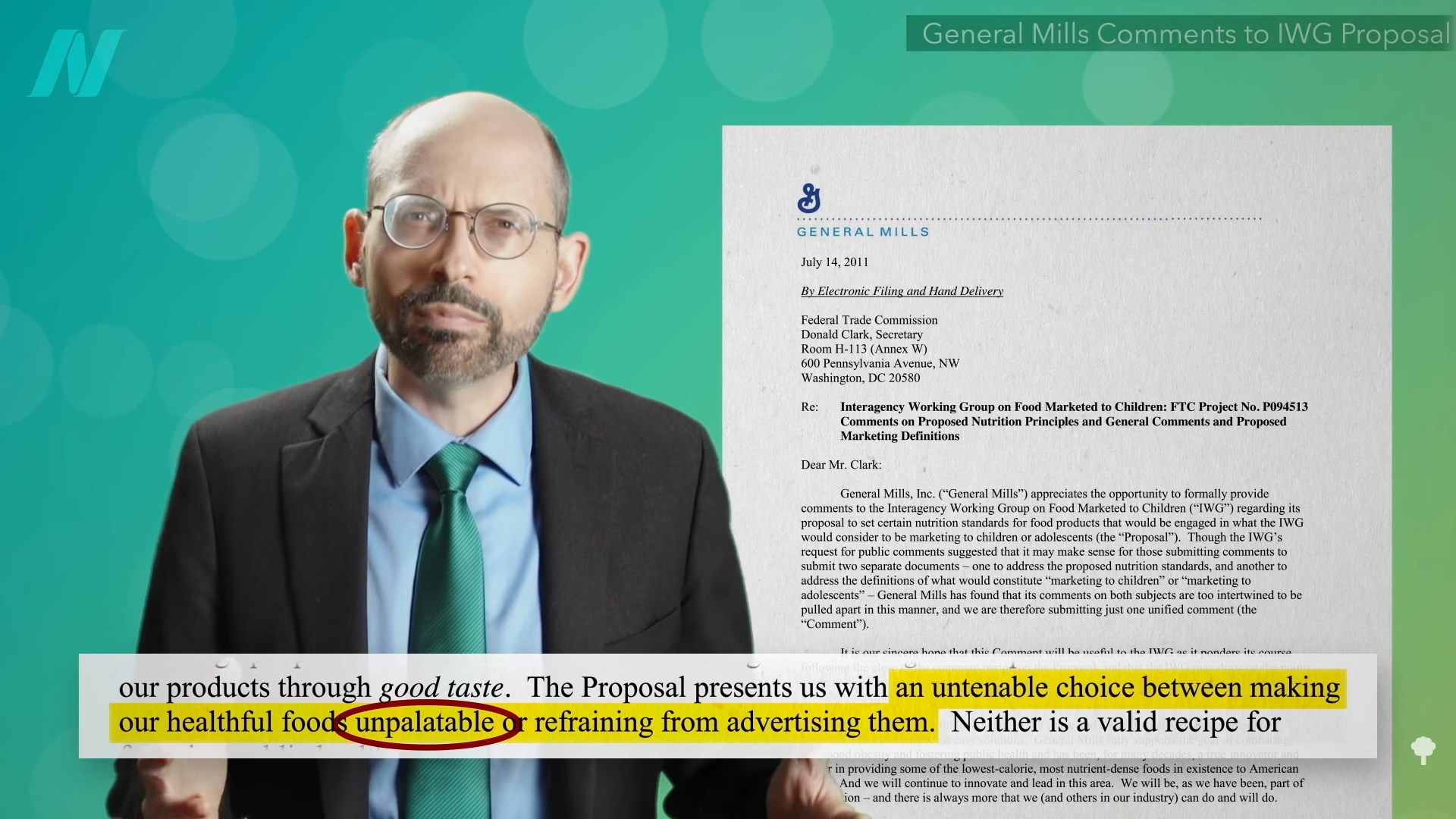

General Mills offers the “Mary Poppins defense,” arguing that those spoonsful of sugar can “help the medicine go down” and explaining that “if sugar is removed from bran cereal, it would have the consistency of sawdust.” As you can see below and at 3:17 in my video, a General Mills representative wrote that the company is presented “with an untenable choice between making our healthful foods unpalatable or refraining from advertising them.” If it can’t add sugar to its cereals, they would be unpalatable? If one has to add sugar to a product to make it edible, that should tell us something. That’s a characteristic of so-called ultra-processed foods, where you have to pack them full of things like sugar, salt, and flavorings “to give flavor to foods that have had their [natural] intrinsic flavors processed out of them and to mask any unpleasant flavors in the final product.”

The president of the Cereal Institute argued that without sugary cereals, kids might not eat breakfast at all. (This is similar to dairy industry arguments that removing chocolate milk from school cafeterias may lead to students “no longer purchasing school lunch.”) He also stressed we must consider the alternatives. As Kellogg’s director of nutrition once put it: “I would suggest that Fruit [sic] Loops as a snack are much better than potato chips or a sweet roll.” You know there’s a problem when the only way to make your product look good is to compare it to Pringles and Cinnabon.

Want a healthier option? Check out my video Which Is a Better Breakfast: Cereal or Oatmeal?.

For more on the effects of sugar on the body and if you like these more politically charged videos see the related posts below.

Finally, for some additional videos on cereal, see Kids’ Breakfast Cereals as Nutritional Façade and Ochratoxin in Breakfast Cereals.