How does Dr. Greger pressure steam his greens?

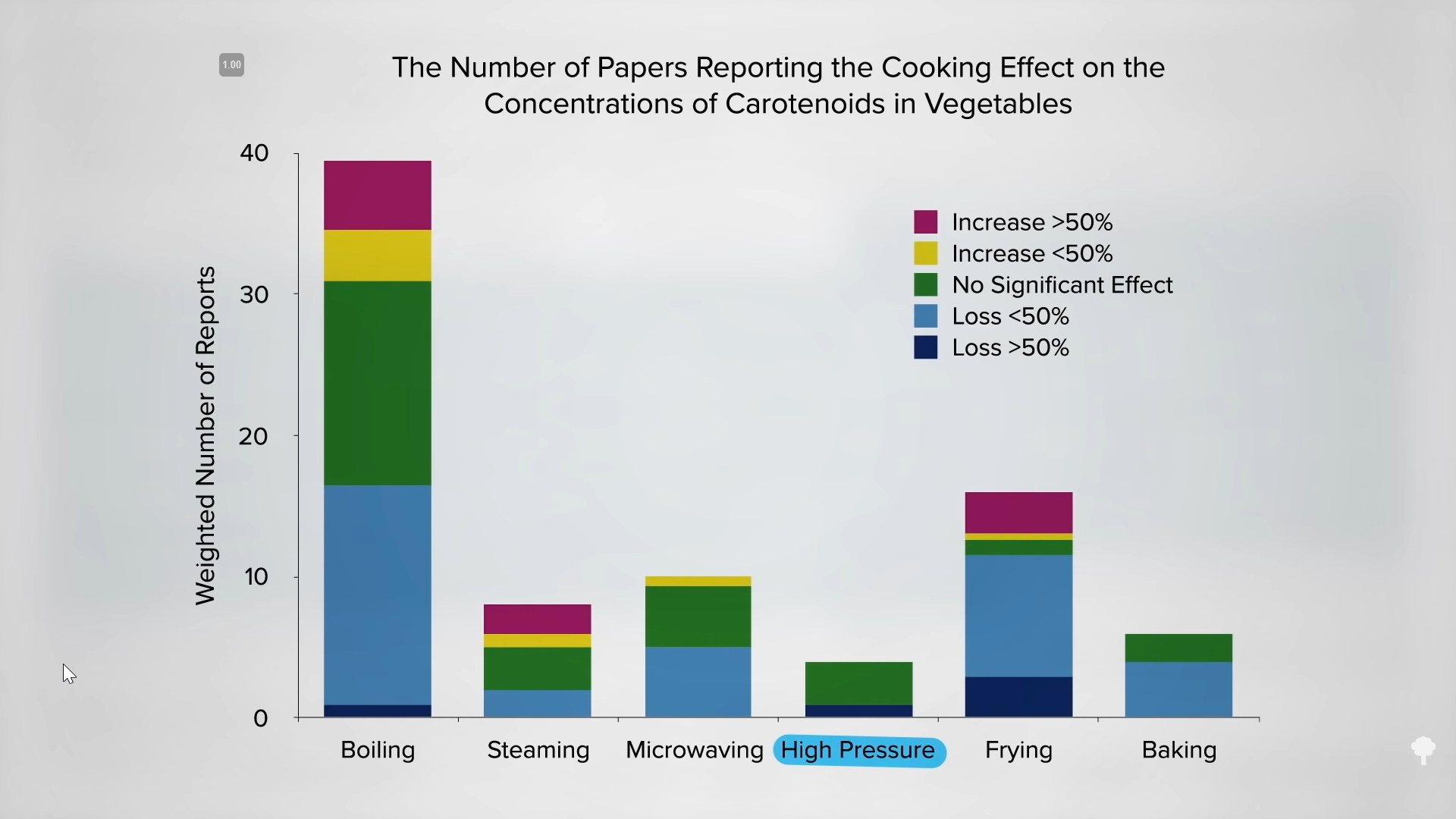

In a review of more than one hundred articles about the effects of cooking on vegetables, researchers tried to find the sweet spot. On the one hand, heat can destroy certain nutrients, but on the other hand, softening the tissues can make them more bioavailable. Researchers settled upon steaming as the best cooking method to preserve the most nutrition because the vegetable isn’t dunked in water or oil where the nutrients can leach out and excessive dry-heat temperatures aren’t reached either. They acknowledge, however, that of all of the common cooking methods, we know the least about pressure cooking, as you can see in the graph below and at 0:37 in my video Does Pressure Cooking Preserve Nutrients?.

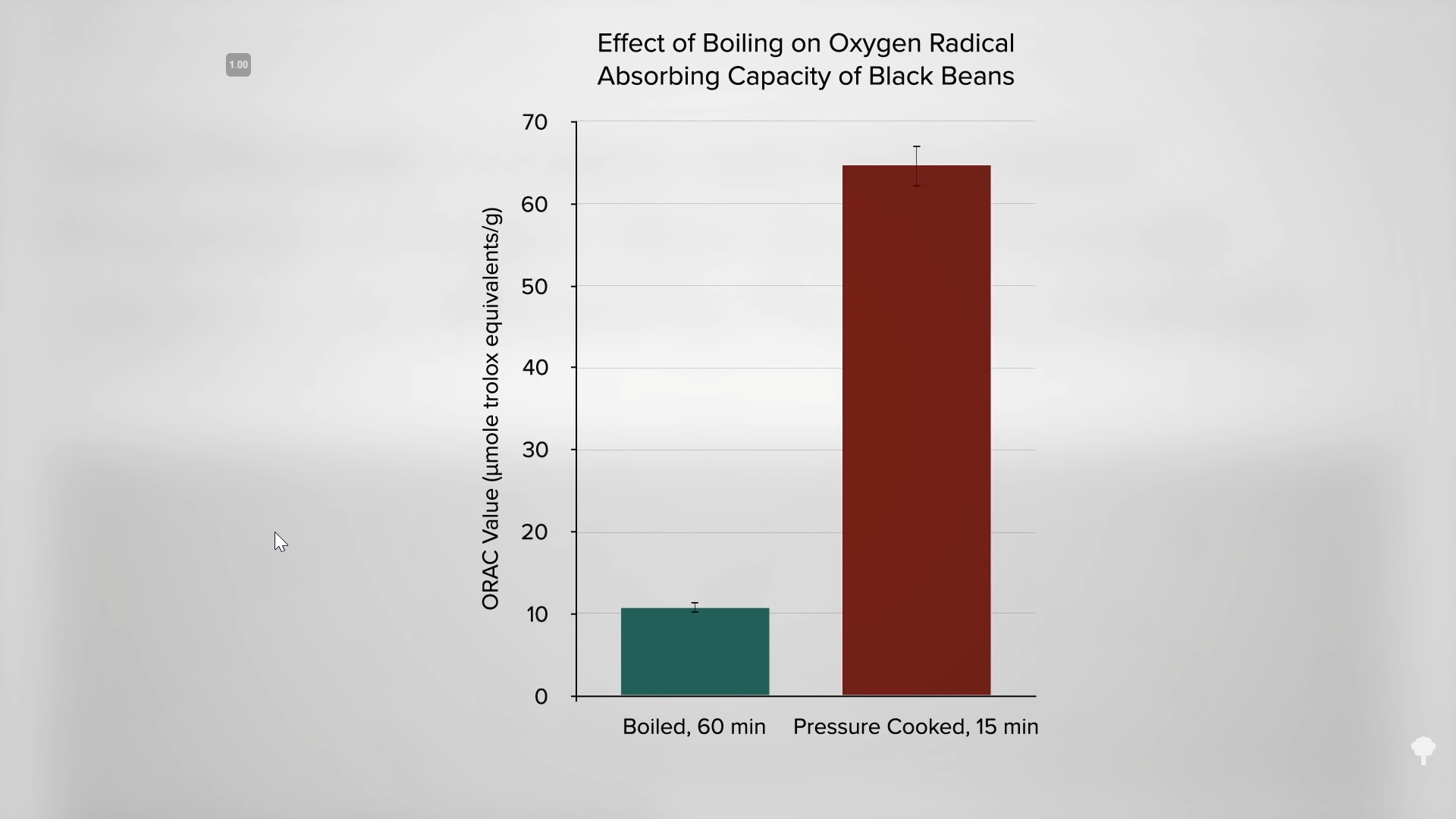

There are all sorts of fancy electric pressure cookers, like the Instant Pot. They’re great for quickly cooking dried beans with just a touch of a button, but what happens to the nutrition? Let’s look at black beans. (See the chart below and at 1:01 in my video.) The antioxidant content of presoaked black beans boiled for about an hour, a usual cooking time, is high, but it’s even higher when pressure cooked for 15 minutes. In fact, researchers found six times the antioxidant levels in the pressure-cooked beans. I’ve been pressure-cooking beans just because I like their texture better (the canned ones can be a bit mushy for me) and dried beans are so cheap compared to canned ones. But now we know they’re tastier, cheaper, and healthier. That’s quite the triple threat.

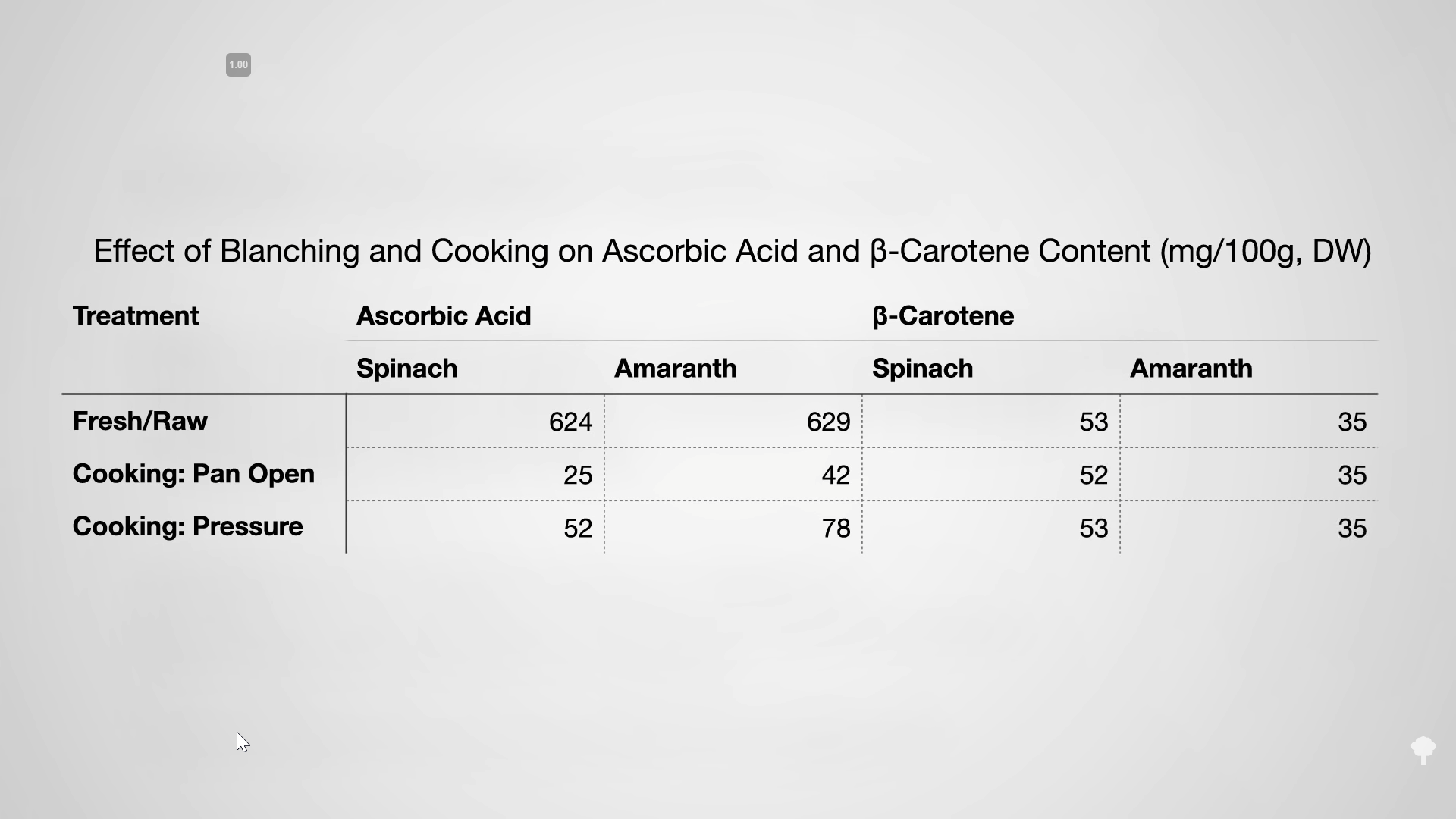

What about pressure-cooking vegetables? As you can see below and at 1:35 in my video, vitamin C is one of the more heat-sensitive nutrients. Researchers found that sautéing spinach or amaranth leaves in a pan for 30 minutes destroyed about 95 percent of the vitamin C, whereas ten minutes in a pressure cooker wiped out only about 90 percent. But who pressure cooks spinach for ten minutes or sautés it for half an hour? Regardless, even then, not many effects were found either way on beta-carotene levels.

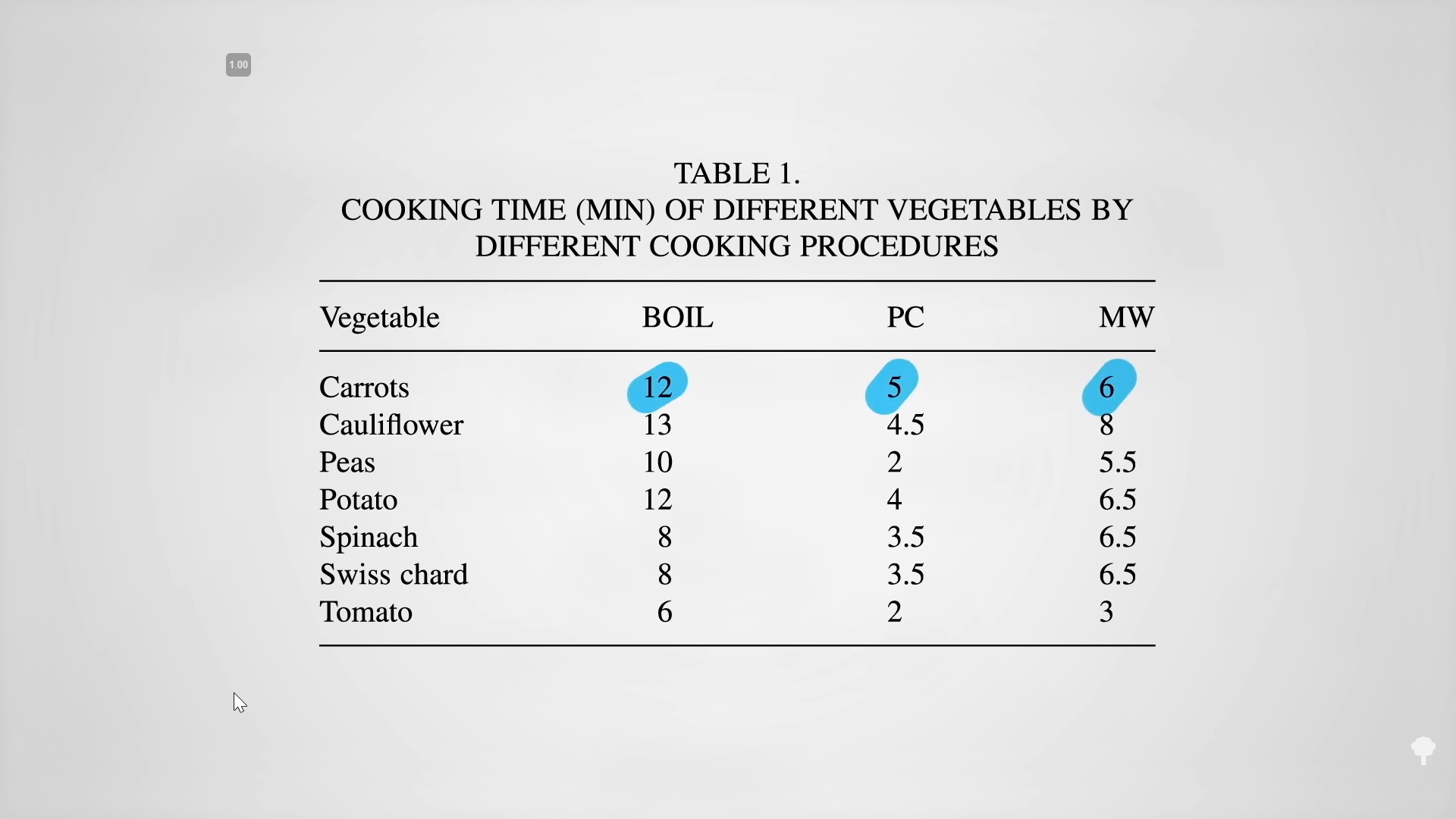

Vitamin C is but one of many antioxidants, though. What about the effects of pressure cooking on overall antioxidant capacity? At 2:07 in my video and below, you can see a table of different cooking methods researchers compared—for example, 12 minutes of boiling, 5 minutes of pressure cooking, and 6 minutes of microwaving carrots. The researchers found that cooking carrots increased their antioxidant potential and pressure cooking nearly doubled their antioxidant value. In contrast, no matter how peas were cooked, their antioxidant capacities took a hit.

Vitamin C is but one of many antioxidants, though. What about the effects of pressure cooking on overall antioxidant capacity? At 2:07 in my video and below, you can see a table of different cooking methods researchers compared—for example, 12 minutes of boiling, 5 minutes of pressure cooking, and 6 minutes of microwaving carrots. The researchers found that cooking carrots increased their antioxidant potential and pressure cooking nearly doubled their antioxidant value. In contrast, no matter how peas were cooked, their antioxidant capacities took a hit.

What about greens? Chard wasn’t affected much across the board, but for spinach, microwaving beat out both pressure cooking and boiling, and pressure cooking beat out boiling—even though pressure cooking is actually boiling, but in less time and at a higher temperature. However, the cooking time appeared to trump the temperature; the researchers saw significantly less nutrient loss when pressure-cooking spinach for three and a half minutes compared to boiling for eight.

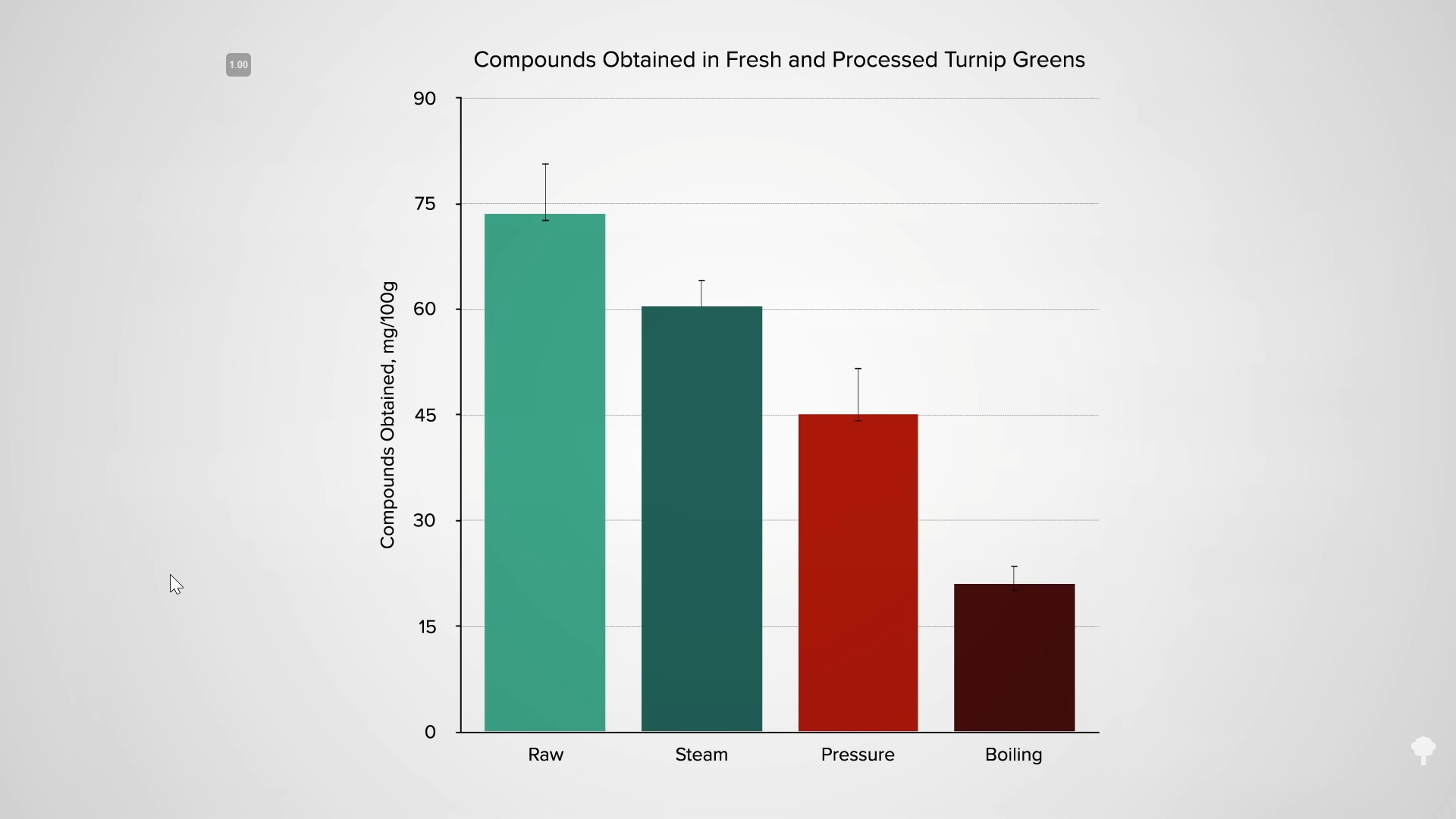

The researchers found the same thing with those magical cancer-fighting glucosinolate compounds in cruciferous greens, which are the healthiest ones, including kale, collards, and turnip greens. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:08 in my video, they had the highest nutrient levels when they were raw. Three-quarters were wiped out by boiling, but less than half were eliminated by pressure cooking. Steaming beat both methods, retaining more nutrients than boiling or pressure cooking, because the greens weren’t dunked in water, which can leach out the nutrients. But, even though the pressure-cooked greens were immersed just as much as the boiled greens were, there were only half the nutrient losses, presumably because it was only half the cooking time—seven minutes pressure cooking compared to 15 minutes boiling.

What if you cut down that time even more by pressure steaming, for instance, by adding a layer of water at the bottom of an electric pressure cooker, dropping it in a metal steaming basket, then putting in the greens and steaming them under pressure? That’s how I cook the greens I eat every day. I’ve always loved collards, especially in Southern-inspired cooking or Ethiopian cuisine, and I found I could get that same melt-in-your-mouth texture simply by steaming them under pressure for zero minutes. Zero minutes? Yes. Just set the pressure cooker to zero so it shuts off as soon as it reaches the cooking pressure, then immediately open the quick-release valve to release the steam. The greens turn out tender, a bright emerald, and cooked to perfection. Give it a try, and let me know what you think.

I love covering practical topics—ones we may need to consider day-to-day when making decisions. Check out some of my other videos, including some cooking ones, in the Related Videos below.