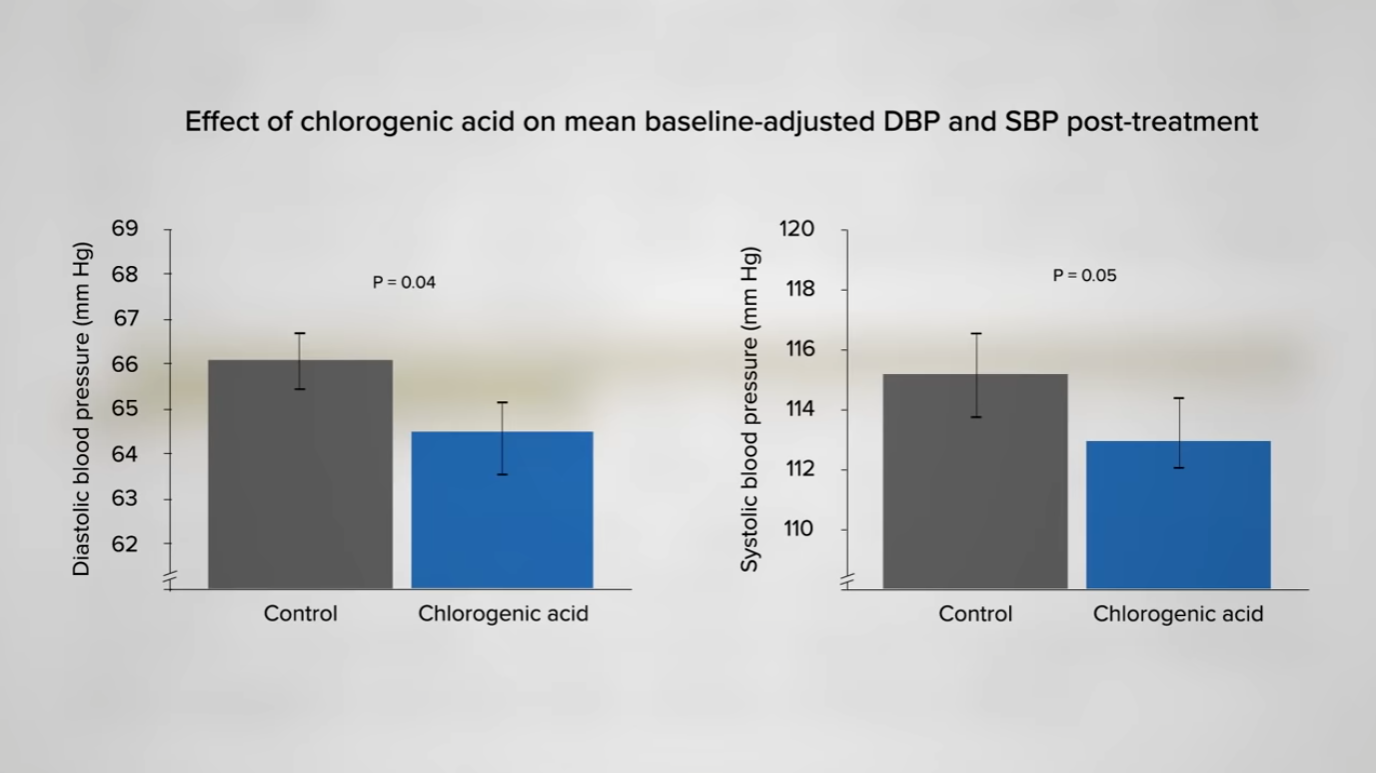

I open my video Does Adding Milk Block the Benefits of Coffee? with a graph from a study of mortality versus coffee consumption that suggests coffee drinkers live longer than non-coffee drinkers. Why might that be? Coffee may have beneficial effects on “inflammation, lung function, insulin sensitivity, and depression,” perhaps due in part to a class of polyphenol phytonutrients found in coffee beans called chlorogenic acids, which have been proven to have favorable effects in studies where it was given alone in pill form. Indeed, they have shown beneficial effects, such as “acute blood pressure-lowering activity,” dropping the top and bottom blood pressure numbers within hours of consumption, as you can see in the graph below and at 0:40 in my video. So, which coffee has the most chlorogenic acids? We know how to choose the reddest tomato and the brightest orange sweet potato, indicating that plant pigments are antioxidants themselves. So, how do you choose the healthiest coffee?

More than a hundred coffees were tested. Different ones had different caffeine levels, but the chlorogenic acid levels varied by more than 30-fold. “As a consequence, coffee selection may have a large influence on the potential health potential of coffee intake.” Okay, but if coffee can vary so greatly, what does it mean when studies show that a single cup of coffee may do this or that? Interestingly, coffee purchased from Starbucks had an extremely low chlorogenic acid content, which contributed significantly to widening the range.

The Starbucks coffee averaged ten times lower than the others. Could it be that Starbucks roasts its beans more? Indeed, the more you roast, the less chlorogenic acid content there is; chlorogenic acid content appears to be partially destroyed by roasting. Caffeine is pretty stable, but a dark roast may wipe out nearly 90 percent of the chlorogenic acid content of the beans. The difference between a medium light roast and a medium roast was not enough to make a difference in total antioxidant status in people’s bloodstreams after drinking them, and they both gave about the same boost. Other factors, such as how you prepare it or decaffeination, don’t appear to have a major effect either. What about adding milk?

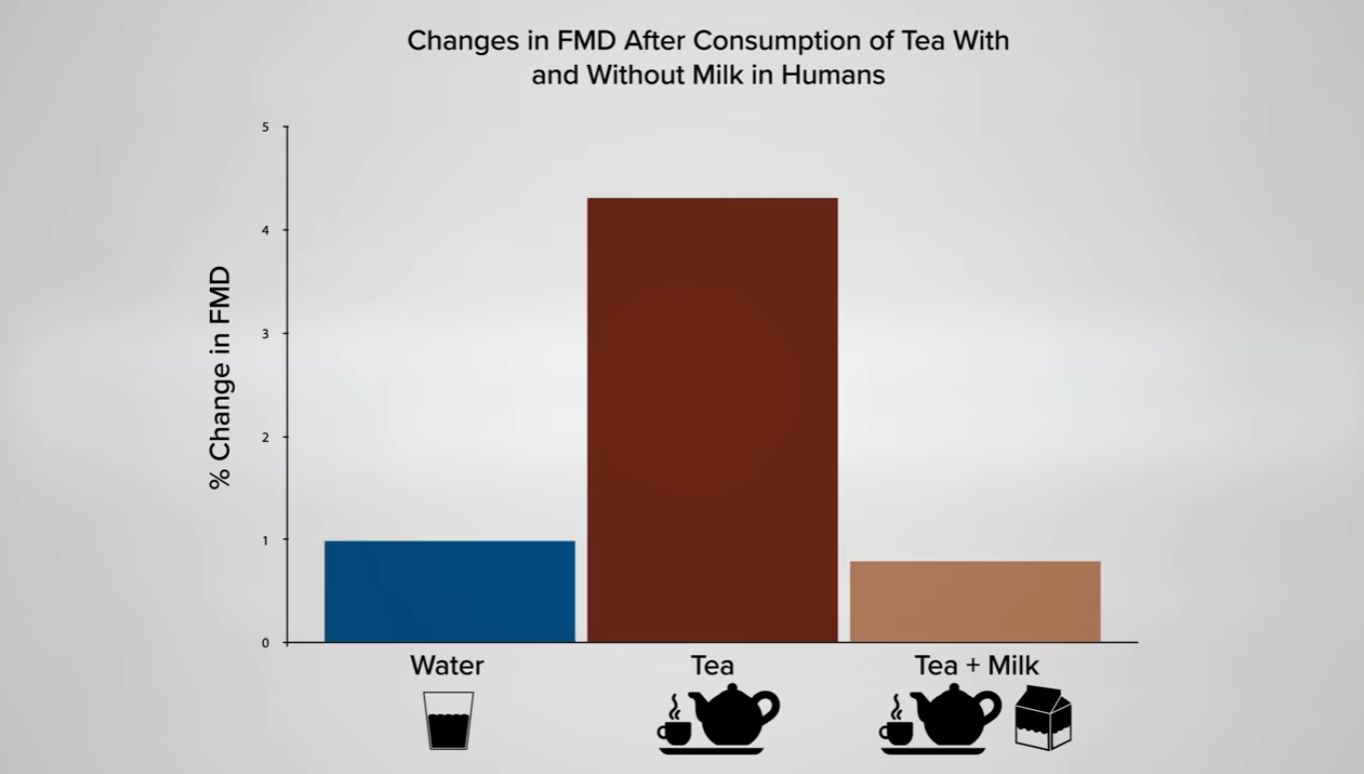

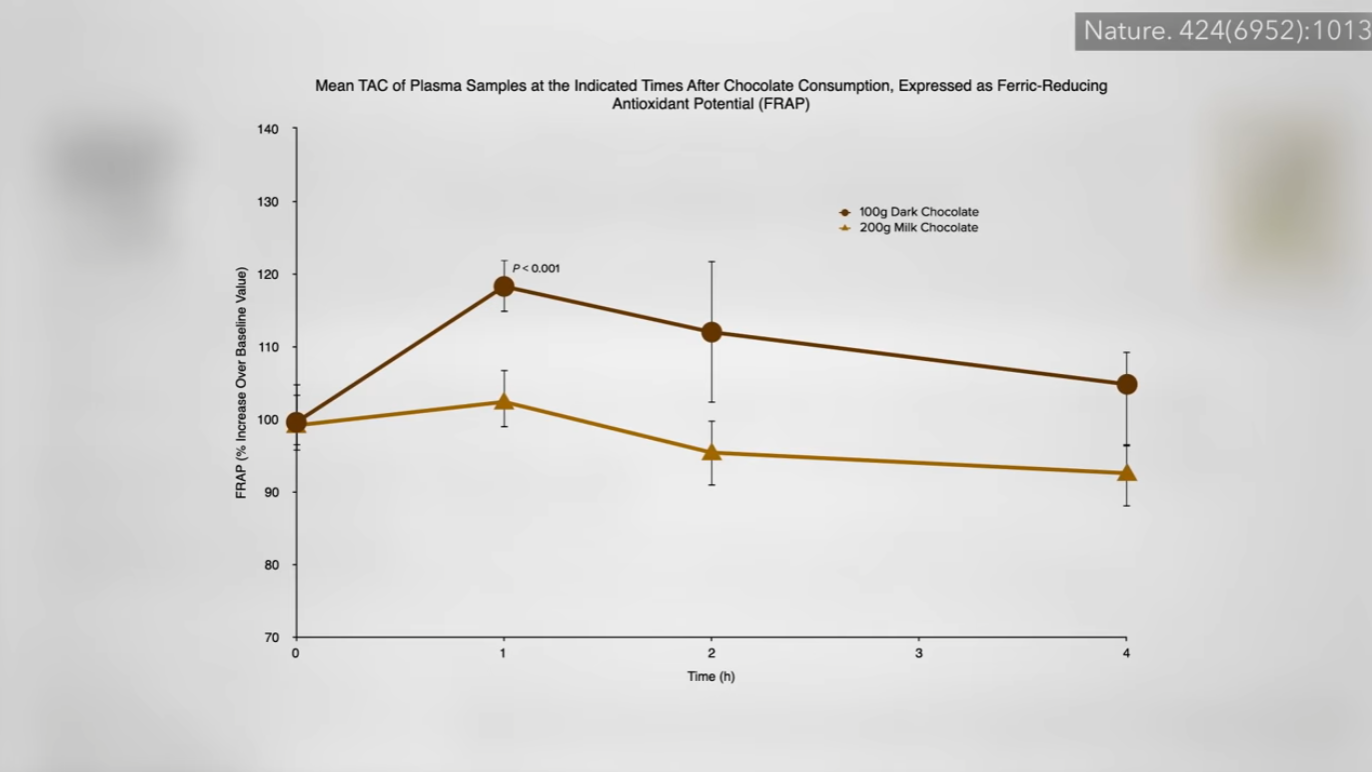

As you can see in the graph below and at 2:37 in my video, the study found that we get a big boost in artery function after drinking tea, but, if we drink the same amount of tea with milk, it’s as if we never drank the tea at all. It’s thought that the milk protein casein is to blame, by binding up the tea phytonutrients. “The finding that the tea-induced improvement in vascular function in humans is completely attenuated after addition of milk may have broad implications on the mode of tea preparation and consumption.” In other words, maybe we should not add milk to tea. In fact, maybe we shouldn’t put cream on our berries either. Milk proteins appear to have the same effect on berry phytonutrients, as well as chocolate, as you can see in the graph below and at 3:15 in my video. If you eat milk chocolate, nothing much happens to the antioxidant power of your bloodstream, but within an hour of eating dark chocolate, you get a nice spike in antioxidant power.

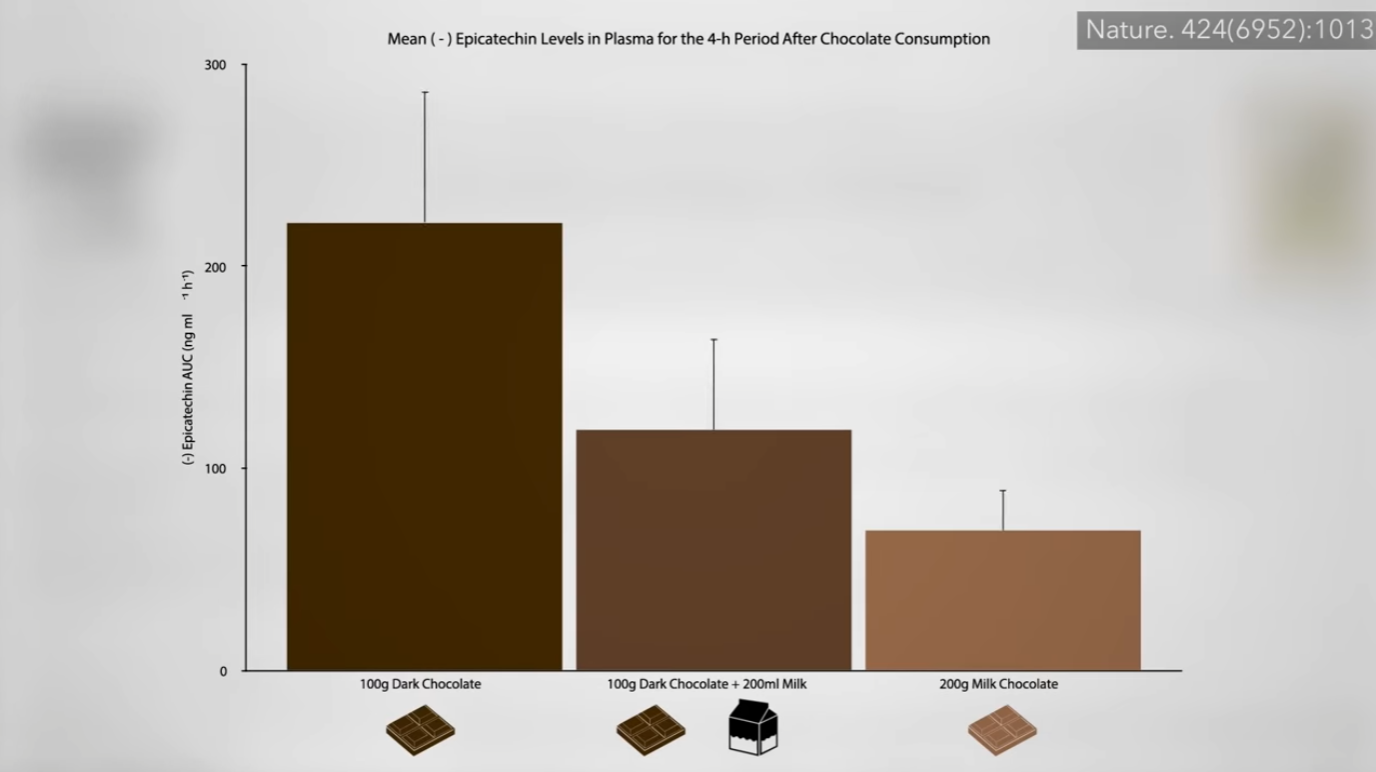

Is this because the milk in milk chocolate crowds out some of the antioxidant-rich cocoa? Milk chocolate may only be 20 percent cocoa, whereas a good dark chocolate may be made of 70 percent or more cocoa solids. That’s not all, though. How much of this cocoa phytonutrient gets into your bloodstream when you eat dark chocolate compared to milk chocolate? If you eat the same amount of dark chocolate with a glass of milk, it blocks about half of the antioxidant power, as you can see in the graph below and at 3:43 in my video.

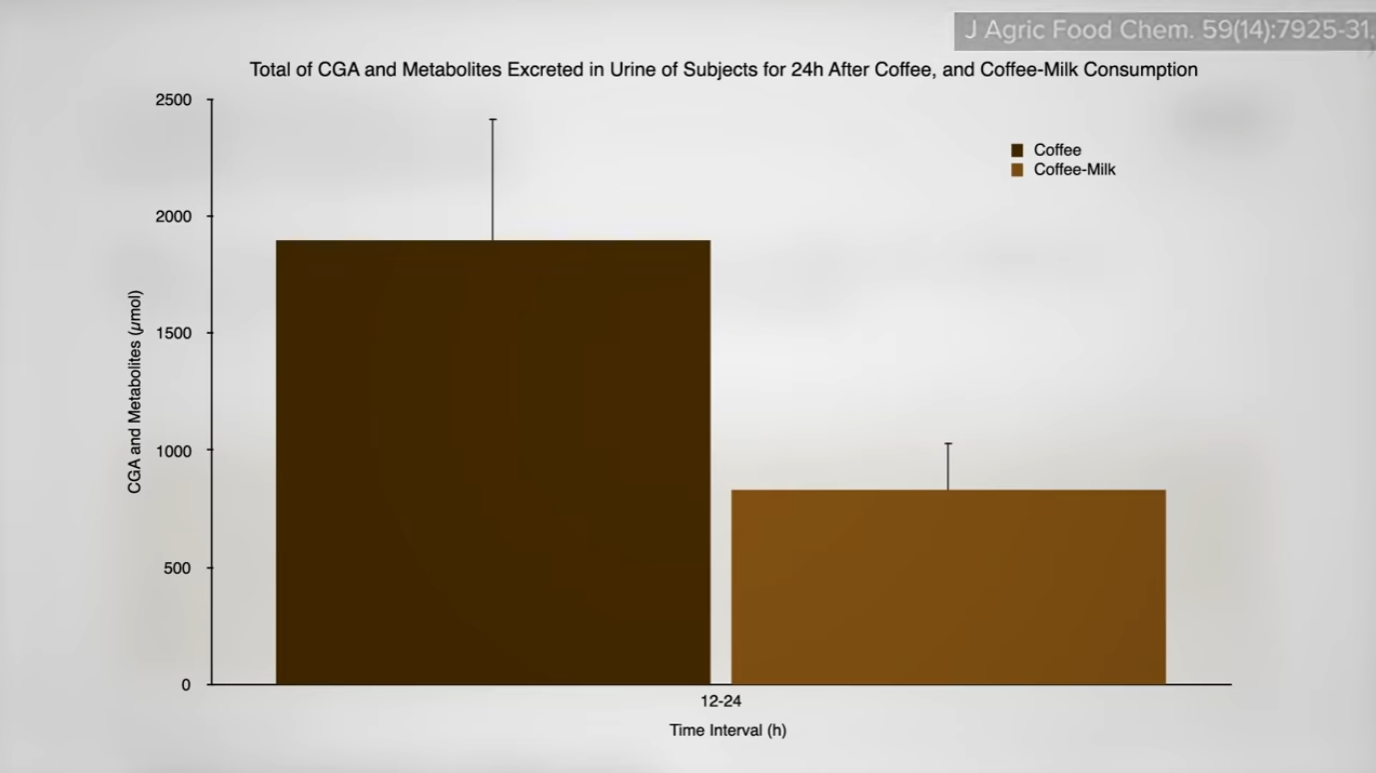

What about coffee beans? When milk was added to coffee in a test tube, the antioxidant activity decreased by more than half with just a splash of milk and reduced by 95 percent in a latte or another preparation with a lot of milk. But, what happens in a test tube doesn’t necessarily happen in a human. You don’t know until you put it to the test. And, indeed, as you can see at 4:22 in my video, over the course of a day, significantly fewer chlorogenic acids made it into people’s bloodstreams when they drank their coffee with milk as compared to black. The added milk cut their absorption of chlorogenic acids by more than half.

What about soymilk? In a test tube, coffee phytonutrients appear to bind to egg and soy proteins, as well as dairy proteins. Computer modeling shows how these coffee compounds can dock inside the nooks and crannies of dairy, egg white, and soy proteins, but what happens in a test tube or computer simulation doesn’t necessarily happen in a human. Eggs haven’t been put to the test, so we don’t know if having omelets with your black coffee would impair absorption. And soymilk?

Soymilk has some inherent benefits over cow’s milk, but does it have the same nutrient-blocking effects as dairy? The answer is no. There is no significant difference in the absorption of coffee phytonutrients when we drink our coffee black or with soymilk. Soy proteins appear to bind initially to the coffee compounds in the small intestine, but then our good bacteria can release them so they can be absorbed in the lower intestine. So, “considering the reversible nature of binding,” it doesn’t seem to be as relevant if you add soymilk, but skip the dairy milk.

I explore the effects of dairy on the health benefits of berries in my video Benefits of Blueberries for Blood Pressure May Be Blocked by Yogurt.

Wondering about other milks? Almond, rice, and coconut-based milks have so little protein that I doubt there would be a blocking effect, but they have never been tested directly to my knowledge.