Ground ginger powder is put to the test for weight loss and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Ginger has been used in India and China for thousands of years to treat illnesses, but so has mercury, so that doesn’t really tell you much. That’s what we have science for. But, when you see article titles in the medical literature like “Beneficial Effects of Ginger…on Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: A Review,” for example, you may not be aware the researchers are talking about the beneficial effects of ginger on fat rats. Why don’t they just conduct human clinical studies? That may be attributed to “ethical issues” and “limited commercial support,” for instance. Limited commercial support I can see: Ginger is dirt cheap, so who’s going to pay for the study? But ethical issues? We’re just talking about giving people some ginger.

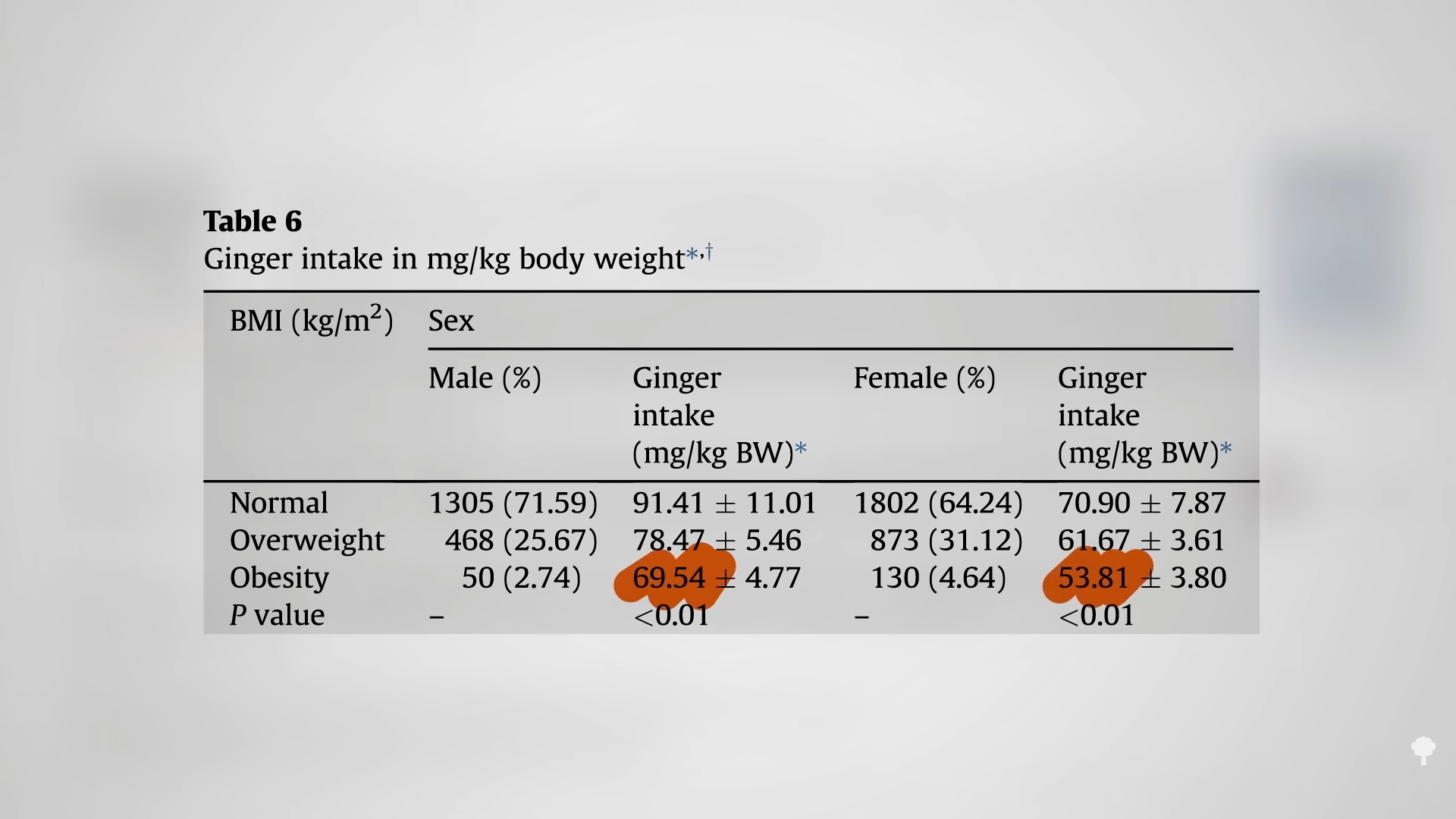

Cross-sectional studies in which you take a snapshot in time of ginger consumption and body weight are relatively inexpensive and easy to do. Researchers have found that people who are obese tend to eat significantly less ginger, so they suggest this “demonstrated that the use of ginger could have relevance for weight management.” You can see a chart below illustrating this and at 0:59 in my video Benefits of Ginger for Obesity and Fatty Liver Disease. But, maybe ginger consumption is just a marker of more traditional, less Westernized junk-food diets. You don’t know…until you put it to the test.

A randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess the effects of a hot ginger beverage made with two grams of ginger powder in one cup of hot water, so about one teaspoon of ground ginger stirred into a teacup of hot water. That’s about five cents’ worth of ginger. The findings? After drinking the ginger beverage, the participants reported feeling significantly less hungry and, in response to the question “How much do you think you could eat?” described lower prospective food intake.

Since the control was just plain hot water, the participants knew when they were getting the ginger so there could have been a placebo effect. The researchers considered putting the ginger into capsules to do a double-blinded study, but they thought part of the ginger’s effect may actually be through taste receptors on the tongue, so they didn’t want to interfere with that with a capsule.

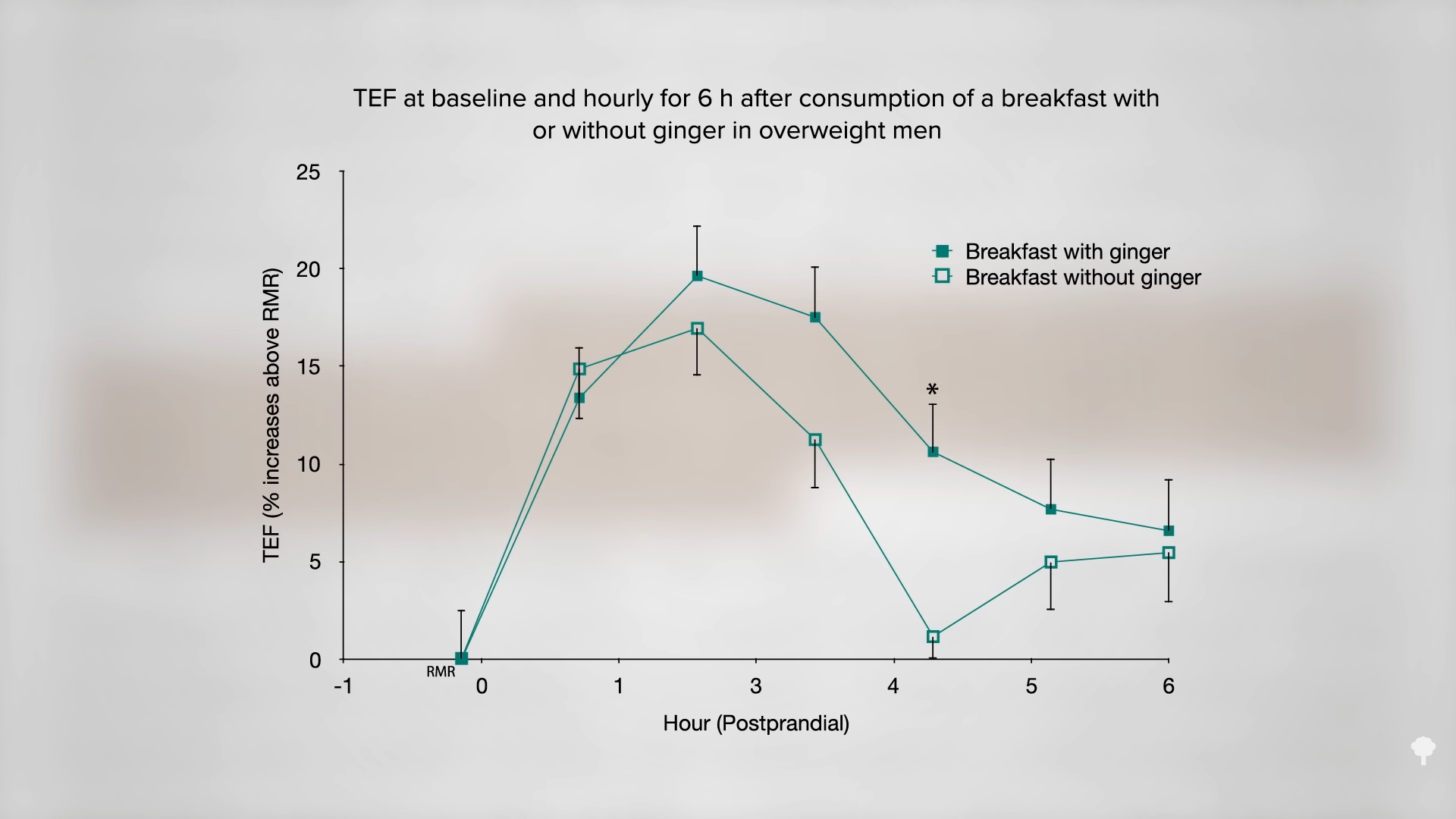

Not all of the effects were just subjective, though. Four hours after drinking the hot beverage, the metabolic rate in the ginger group was elevated compared to control, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:12 in my video. Though, in a previous study, when fresh ginger was added to a meal, there was no bump in metabolic rate. The researchers of the hot ginger beverage study suggest this discrepancy is “likely due to the different method of ginger administration,” giving participants fresh ginger instead of dried ginger powder, and there are dehydration products that form when ginger is dried that may have unique properties.

“Although satiety and fullness were greater with ginger compared to control, [the researchers] have no objective measure of food intake.” They didn’t then go on to follow the participants to see if they actually ate less for lunch. The problem is there’s never been a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of that much ginger and weight loss…until now.

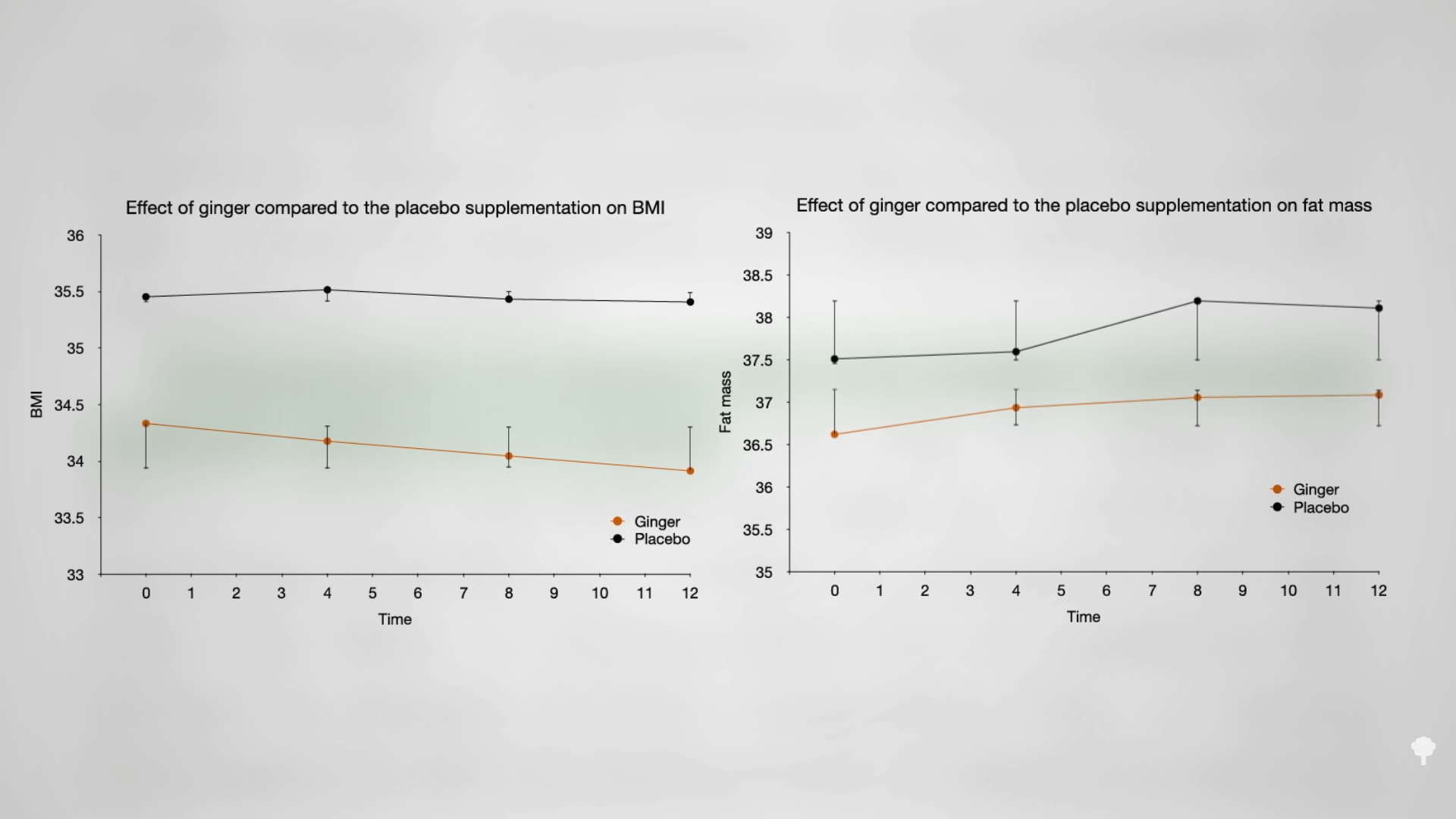

After 12 weeks of that same teaspoon of ginger powder a day, but this time hidden in capsules, consumption of ginger “significantly reduced BMI,” that is, body mass index. As you can see in the graphs at 3:12 in my video, there was no change in the placebo group, but there was a drop in the ginger group. Body fat estimates didn’t really change, though, but that was kind of the whole point.

What about using ginger to pull fat out of specific organs, like the liver? Evidently, “treatment with ginger ameliorates fructose-induced fatty liver…in rats.” You know what else would have worked? Not feeding them so much sugar in the first place. We aren’t rats, though. We didn’t have this type of study on humans…until now: “Ginger Supplementation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study” in which participants were given a teaspoon of ginger a day or placebo for 12 weeks.

All of the subjects were told to get more fiber and exercise, and to limit their dietary cholesterol intake. (My video How to Prevent Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease discusses why this is important.) So, even the placebo group should improve. And how did the ginger group do? Any better? Yes. Daily consumption of just one teaspoon of ground ginger a day “resulted in a significant decrease in inflammatory marker levels,” improvements in liver function tests, and a drop in liver fat. All for five cents’ worth of ginger powder a day. And what are the side effects? A few gingery burps?

I searched for downsides and didn’t find any other than ginger paralysis. What? Indeed, “in 1930, thousands of Americans were poisoned by an illicit extract.” Hold on. Who drinks ginger extract? The year 1930 was during the Prohibition, so some people bought ginger extract as a legal way to get their hands on alcohol. “It was the poor man’s way of getting a drink of liquor.” But, “bootleggers had taken advantage of the demand for this old household remedy as an alcoholic beverage” and swapped in a cheaper ginger substitute—a varnish compound—”in order to make greater money profits.” The moral of the story: Don’t drink varnish.

The video about the dietary cholesterol effect that I referred to is How to Prevent Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Oats might help, too, as you can see in Can Oatmeal Help Fatty Liver Disease?. And, for even more on fatty liver disease, check out The Best Diet for Fatty Liver Disease Treatment and How to Avoid Fatty Liver Disease.