Calories eaten in the morning count less than calories eaten in the evening, and they’re healthier, too.

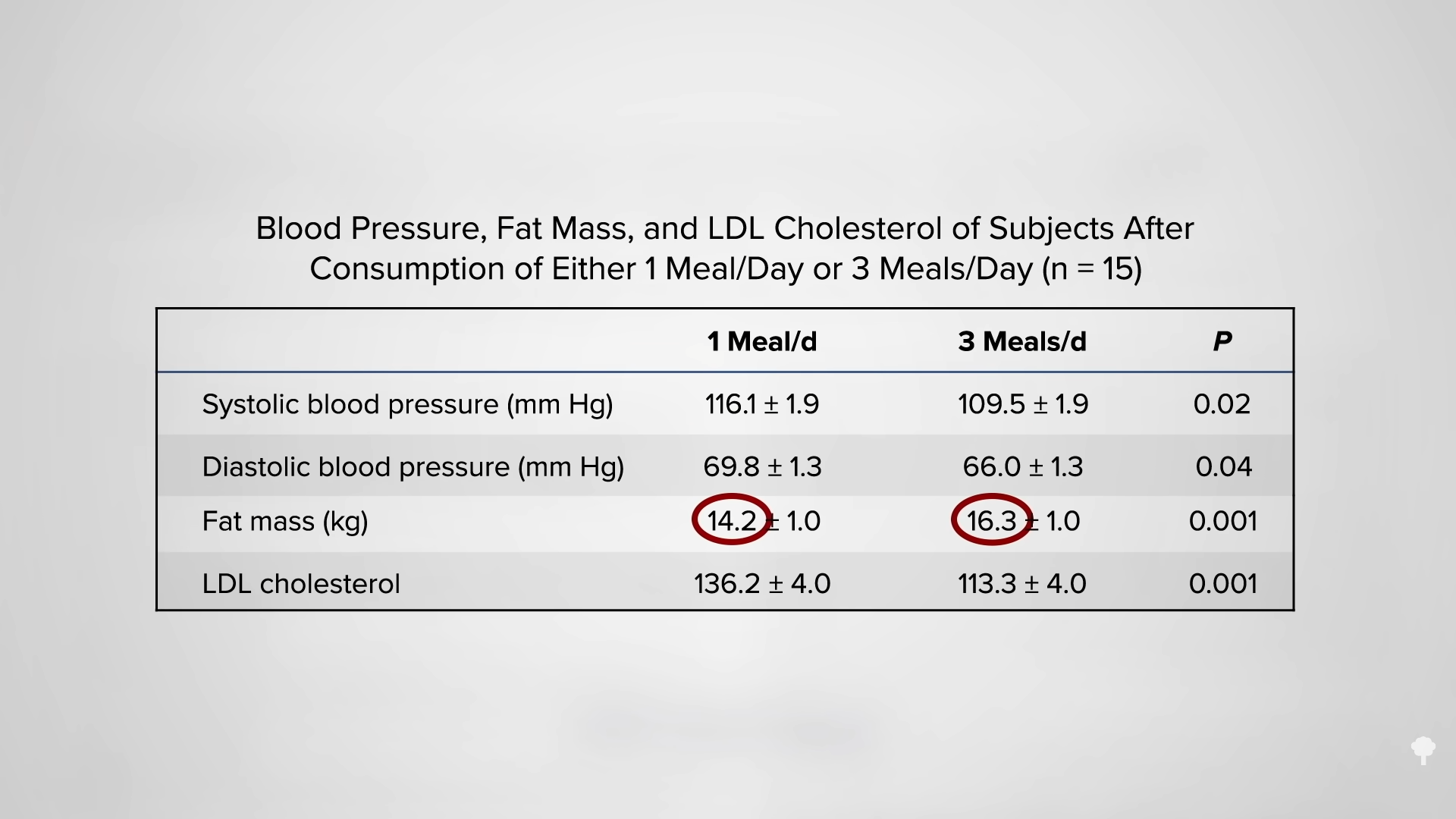

Time-restricted feeding, where you limit the same amount of eating to a narrow evening window, has benefits compared to eating in the evening and earlier in the day, but it also has adverse effects because you’re eating so much, so late, as you can see below and at 0:12 my video The Benefits of Early Time-Restricted Eating.

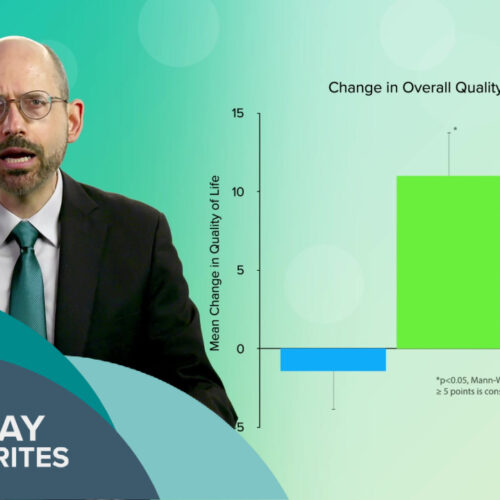

The best of both worlds was demonstrated in 2018 when researchers put time-restricted feeding into a narrow window earlier in the day. As you can see below and at 0:28 in my video, individuals who were randomized to eat the same food, but only during an 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. eating window, experienced a drop in blood pressure, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance, even when all of the study subjects were maintained at the same weight. Same food, same weight, but with different results. The drops in blood pressure were extraordinary, from 123/82 down to 112/72 in five weeks, and that is comparable to the effectiveness of potent blood-pressure drugs.

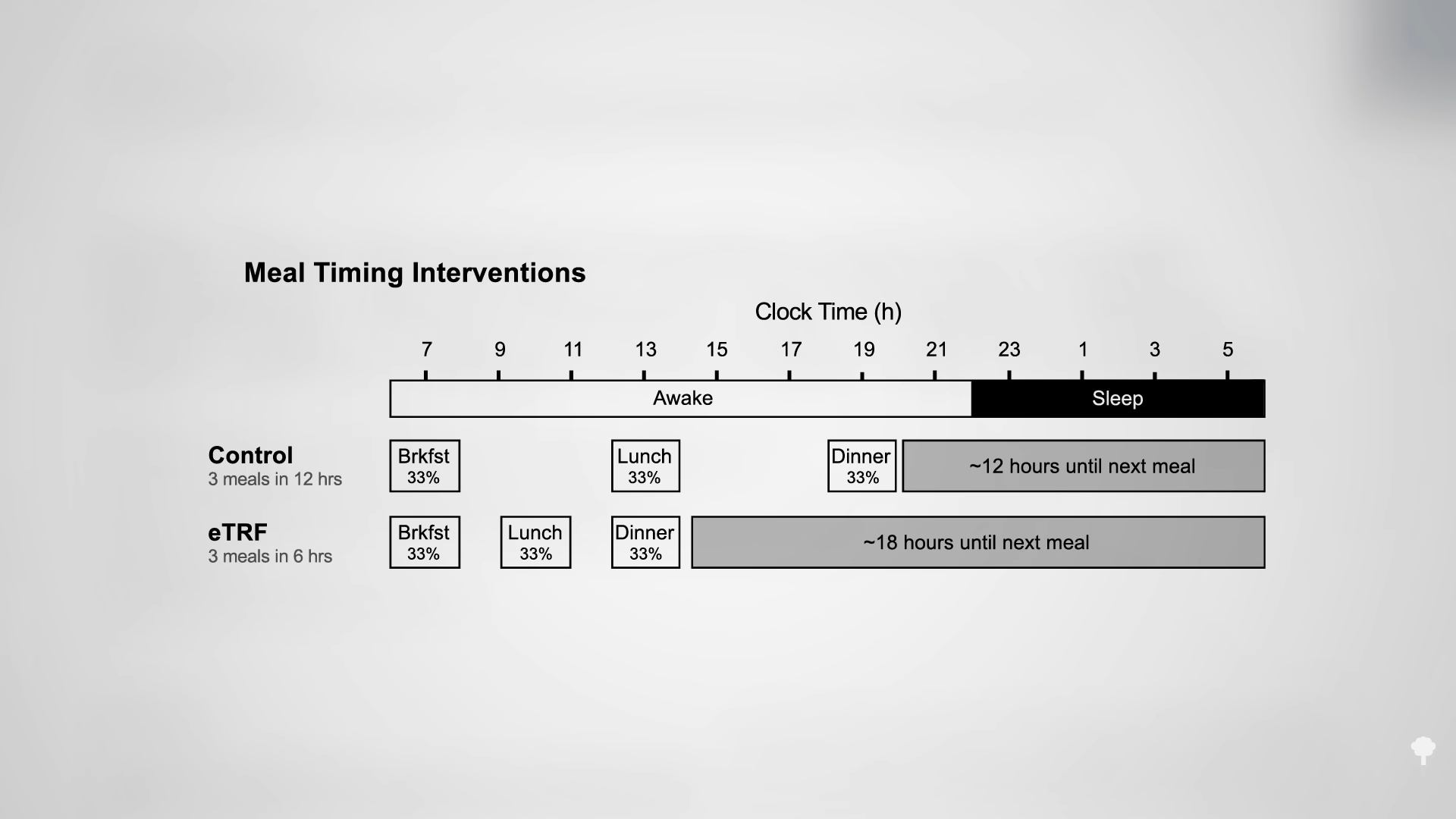

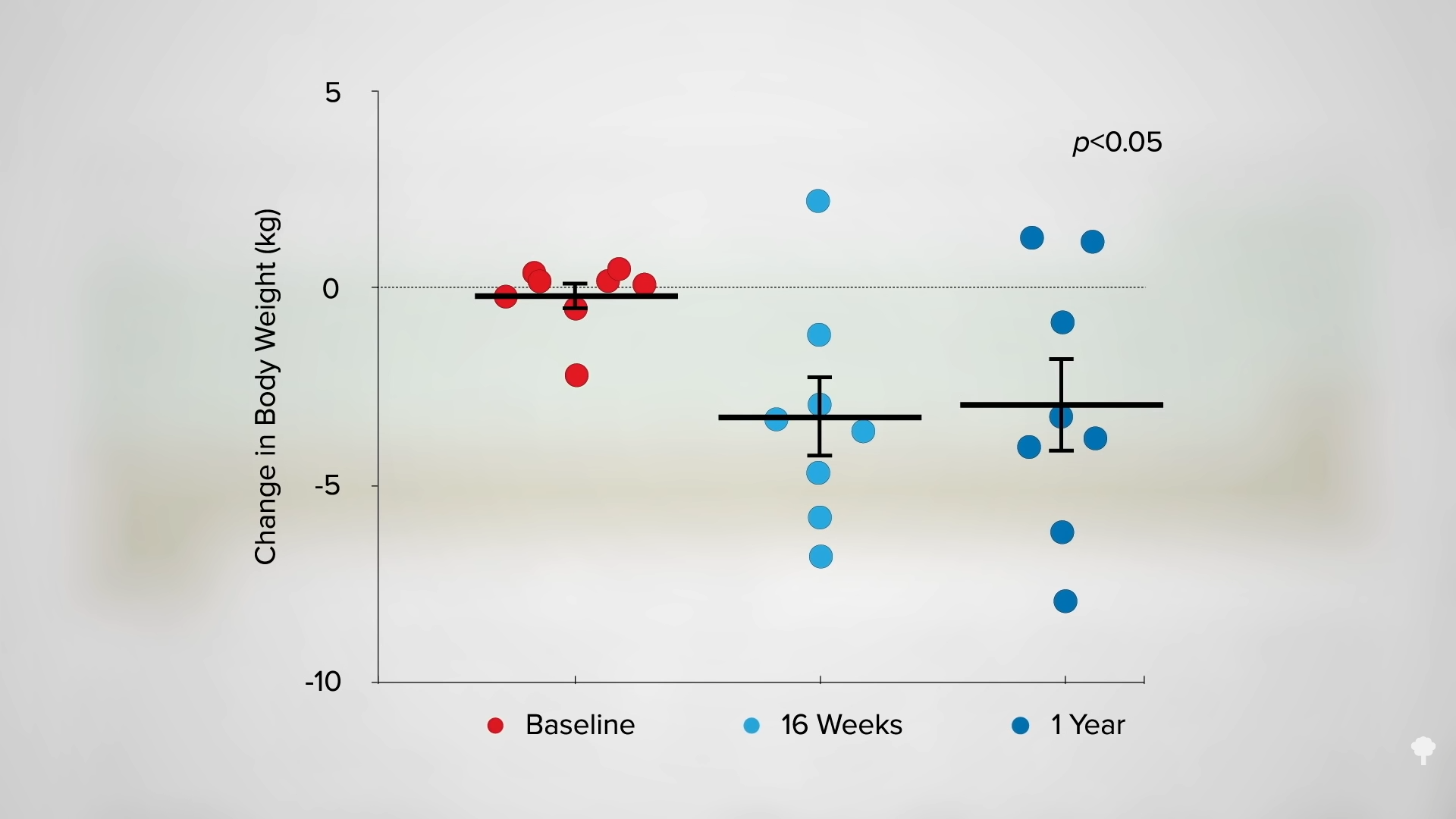

The longest study to date on time-restricted feeding only lasted for 16 weeks. It was a pilot study without a control group that involved only eight people, but the results are still worth noting. Overweight individuals, who, like most of us, had been eating for more than 14 hours a day, were instructed to stick to a consistent 10- to 12-hour feeding window of their own choosing, as you can see below and at 1:17 in my video. On average, they were able to successfully reduce their daily eating duration by about four and a half hours and had lost seven pounds within 16 weeks.

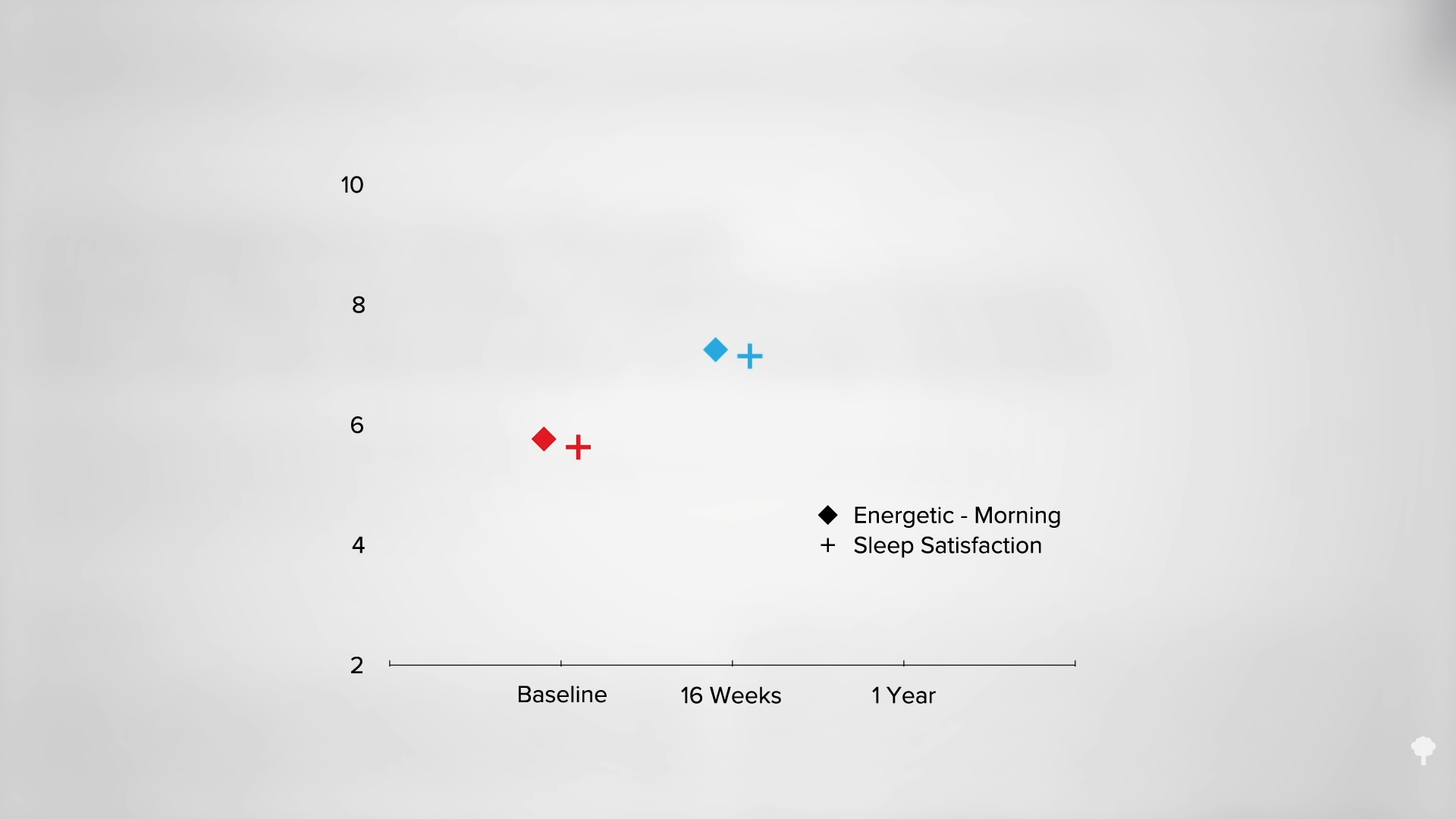

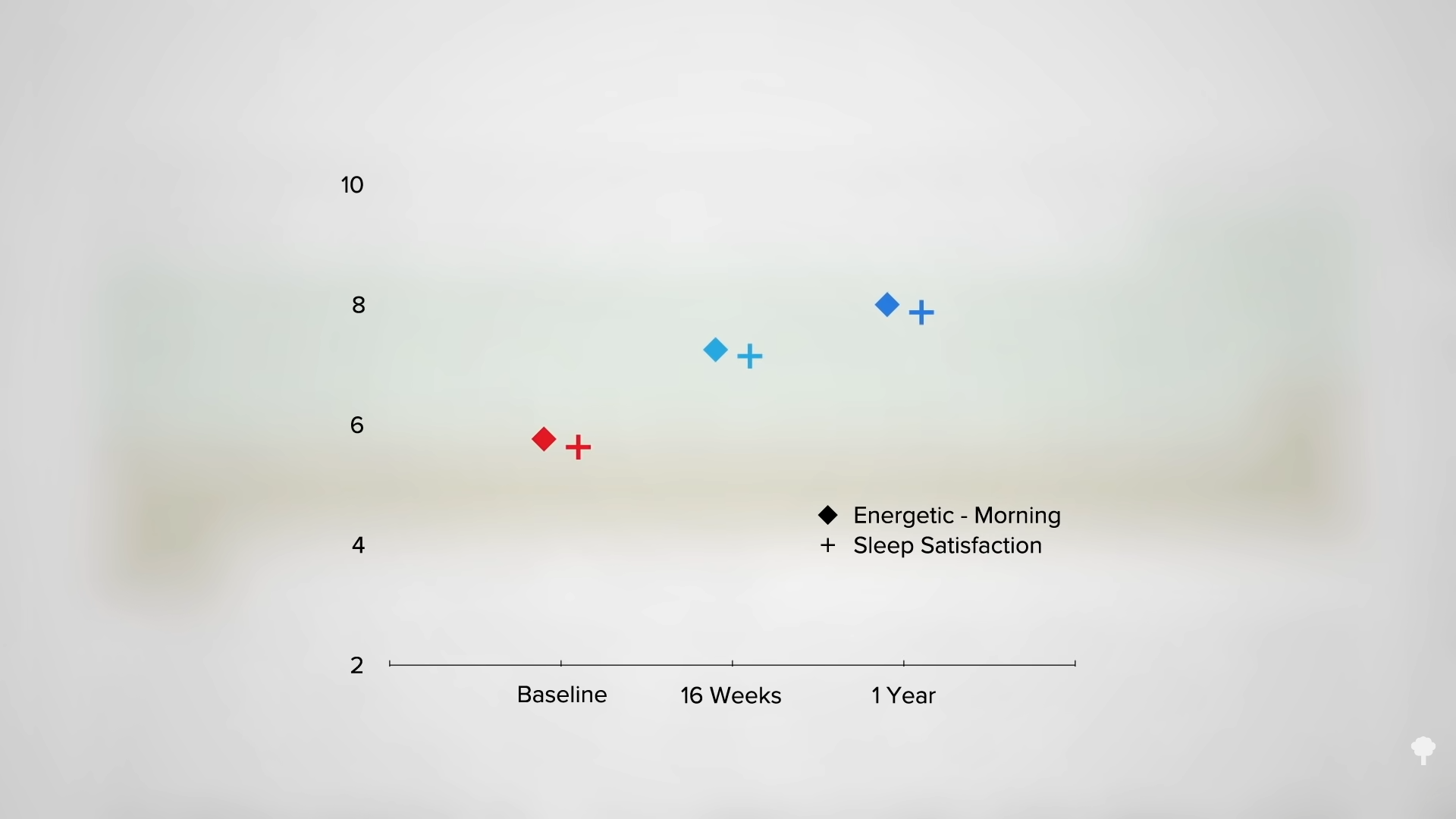

They also reported feeling more energetic and sleeping better, as seen in the graph below and at 1:32 in my video. This may help explain why “all participants voluntarily expressed an interest in continuing unsupervised with the 10-11 hr time-restricted eating regimen after the conclusion of the 16-week supervised intervention.” You don’t often see that after weight-loss studies.

Even more remarkably, eight months later and even one year post-study, they had retained their improved energy and sleep (see in the graph below and 1:55 in my video), as well as retained their weight loss (see in the graph below and 1:58 in my video)—all from one of the simplest of interventions: sticking to a consistent 10- to 12-hour feeding window of their own choosing.

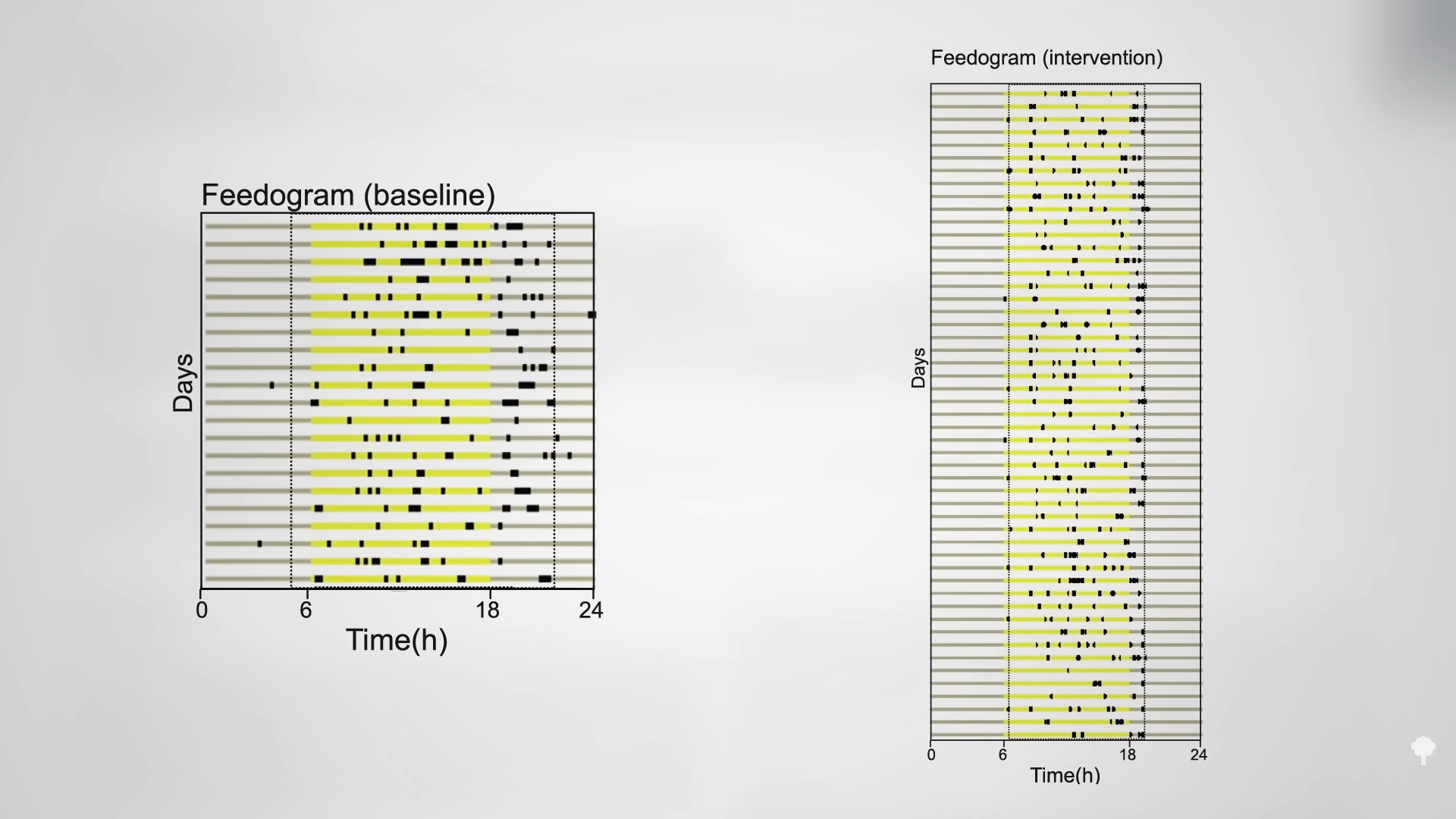

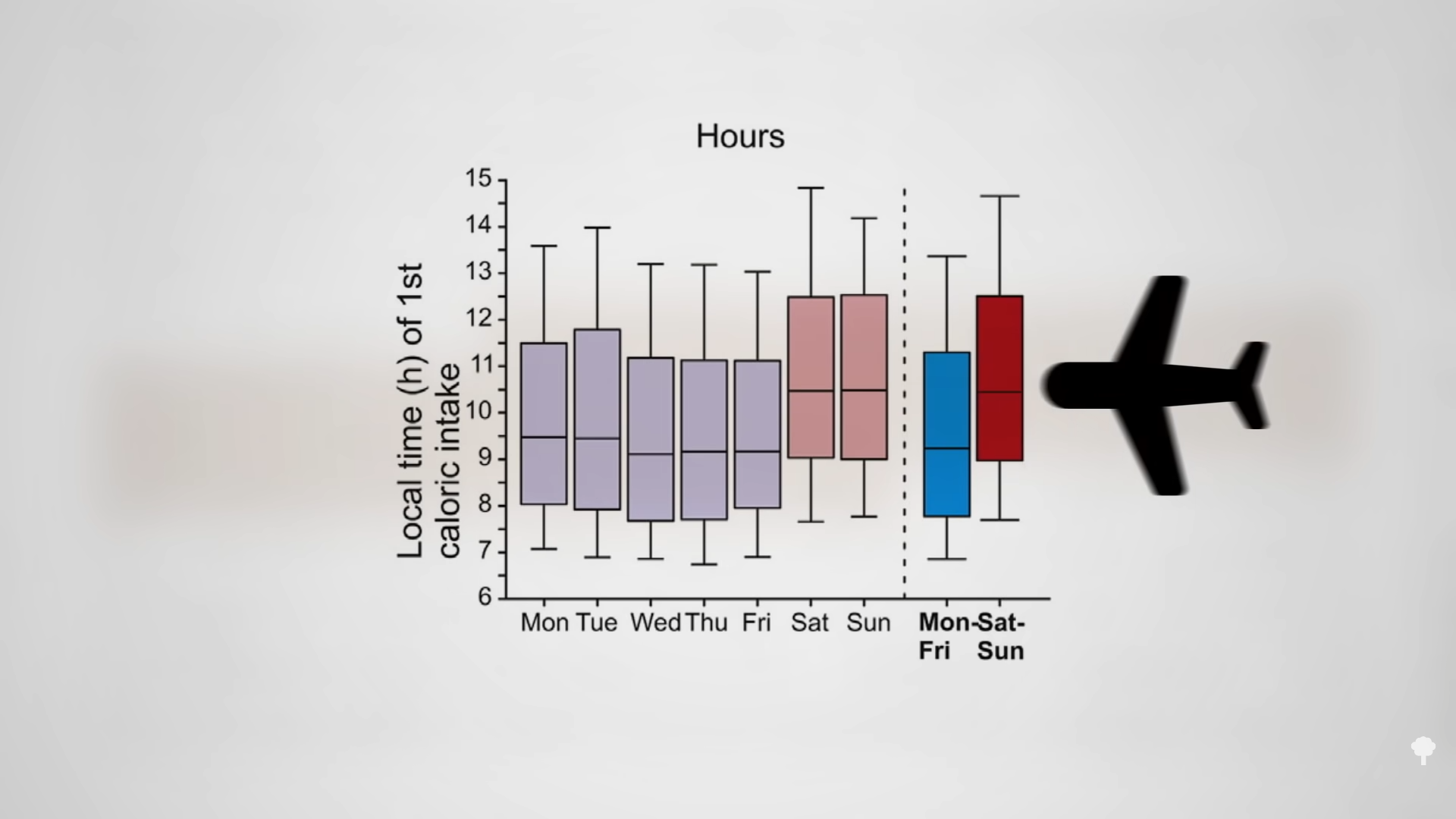

How did it work? Even though the study “participants were not overtly asked to change nutrition quality or quantity,” they appeared to unintentionally eat hundreds of fewer calories a day. With self-selected time frames for eating, you wouldn’t necessarily think to expect circadian benefits, but because they had been asked to keep the eating window consistent throughout the week, “metabolic jet lag could be minimized.” The thinking is that because people tend to start their days later on weekends, they disrupt their own circadian rhythm. And, indeed, it is as if they had flown a few time zones west on Friday evening, then flew back east on Monday morning, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:40 in my video. So, some of the metabolic advantages may have been due to maintaining a more regular eating schedule.

Early or mid-day time-restricted feeding may have other benefits as well. Prolonged nightly fasting with reduced evening food intake has been associated with lower levels of inflammation and has also been linked to better blood sugar control, both of which might be expected to lower the risk of diseases, such as breast cancer. So, data were collected on thousands of breast cancer survivors to see if nightly fasting duration made a difference. Those who couldn’t go more than 13 hours every night without eating had a 36 percent higher risk of cancer recurrence. These findings have led to the suggestion that efforts to “avoid eating after 8 pm and fast for 13 h or more overnight may be a beneficial consideration for those patients looking to decrease cancer risk and recurrence,” though we would need a randomized controlled trial to know for sure.

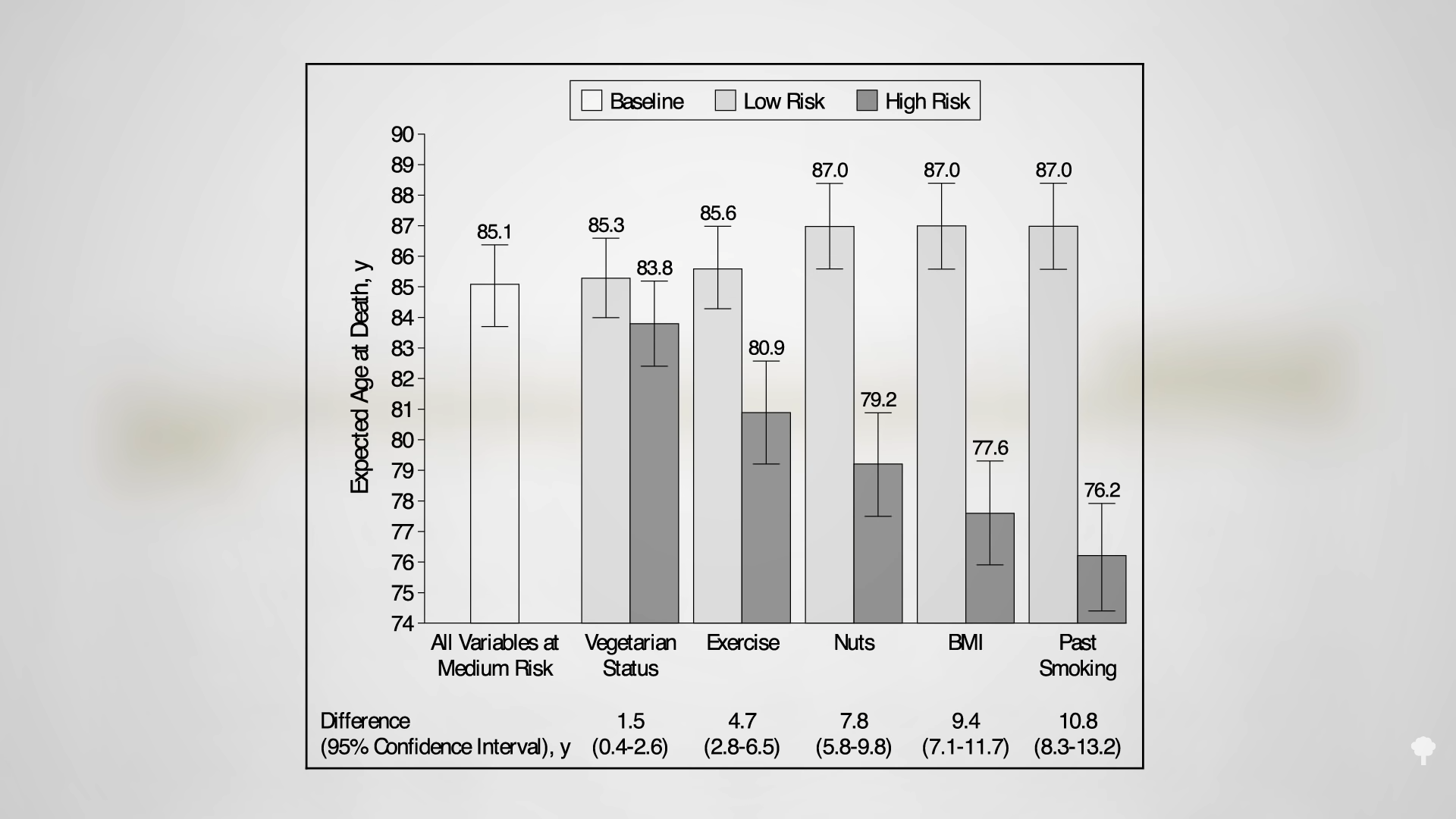

Early time-restricted feeding may even play a role in the health of perhaps the longest-living population in the world, the Seventh-day Adventist Blue Zone in California. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:55 in my video, slim, vegetarian, nut-eating, exercising, non-smoking Adventists live about a decade longer than the general population.

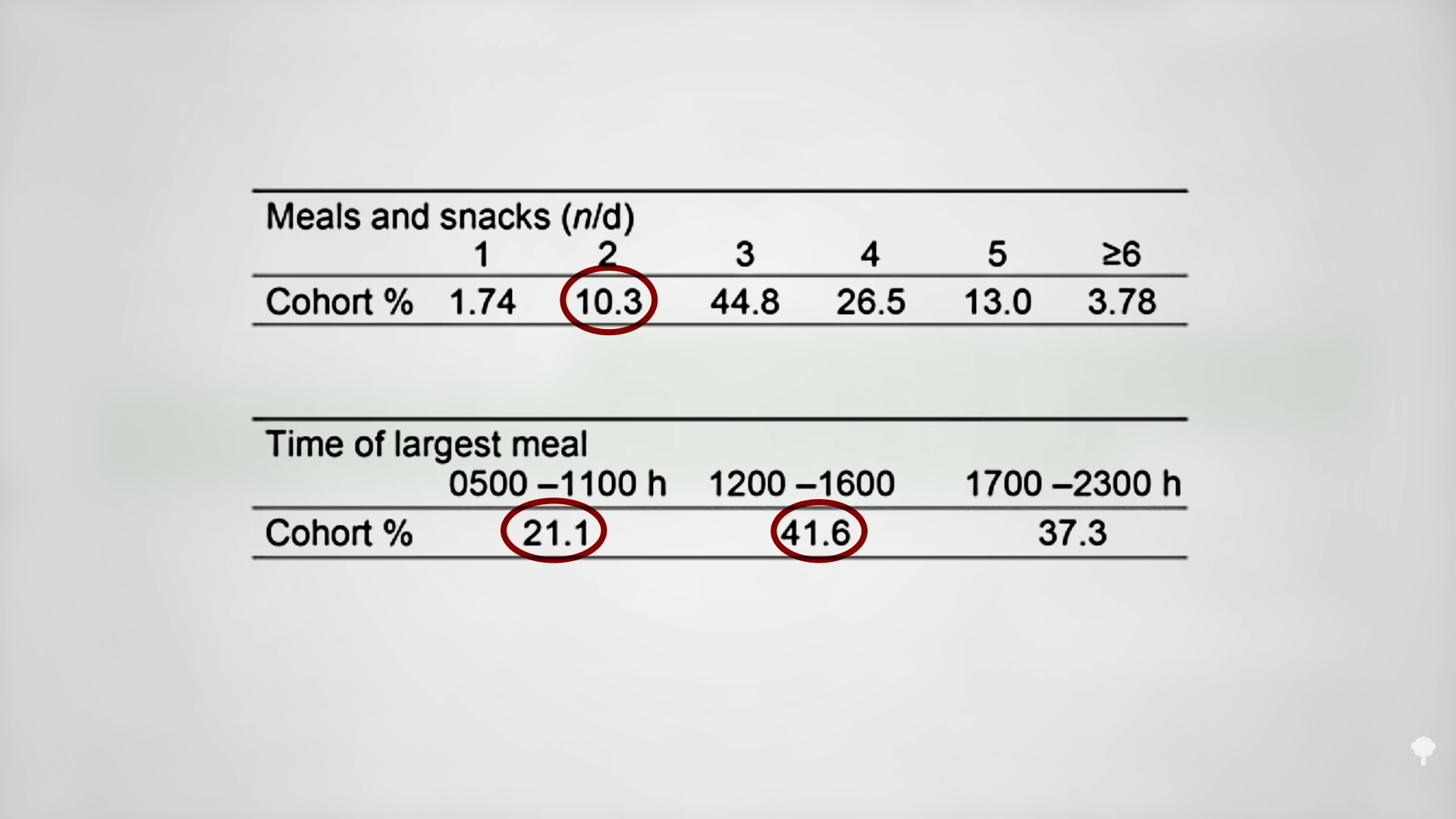

Their greater life expectancy has been ascribed to these healthy lifestyle behaviors, but there’s one lesser-known component that may also be playing a role. Historically, eating two large meals a day, breakfast and lunch, with a prolonged overnight fast, was a part of Adventist teachings. Today, only about one in ten Adventists surveyed were eating just two meals a day. However, most of them, more than 60 percent of them, reported that breakfast or lunch was their largest meal of the day, as you can see below and at 4:26 in my video. Though this has yet to be studied concerning longevity, frontloading one’s calories earlier in the day with a prolonged nightly fast has been associated with significant weight loss over time. This led the researchers to conclude: “Eating breakfast and lunch 5–6 h apart and making the overnight fast last 18–19 h may be a useful practical strategy” for weight control. The weight may be worth the wait.

For more on fasting, click here.

My big takeaway from all of the intermittent fasting research I looked at is, whenever possible, eat earlier in the day. At the very least, avoid late-night eating whenever you can. Eating breakfast like a king and lunch like a prince, with or without an early dinner for a pauper, would probably be best.

For more on fasting, fasting for disease reversal, and fasting and cancer, check the related videos below.